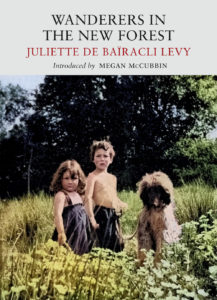

Juliette de Baïracli Levy is known as the ‘grandmother of herbalism’. Originally published in 1958, her book ‘Wanderers in the New Forest’ describes an extraordinary life raising her children and Afghan Hounds in a cabin in the woods. Juliette’s friendships within the local Gypsy community enabled her to record the impact that post-war modernisation was having on their traditions, ancient rights and intimate knowledge of the New Forest. A brand new edition, illustrated with photographs taken by Juliette while living in the forest, is to be published by Little Toller next week. Read an extract below.

For my own part, in my garden, taking as an excuse that it was forest land, I allowed much grass to grow amongst the plants and further tolerated all the weeds which I thought beautiful. This meant that I harboured tracts of buttercups, white clover, white campions, wild pansies, corn poppies and corn marigolds, and I let lesser bindweed festoon the raspberry canes, and honeysuckle grow wherever it was able to establish itself. Then also there were the weeds which we liked as salad foods, and they were all permitted in the garden and did not have to keep to one place either: dandelion, sorrel, hare’s lettuce, chickweed, hedge parsley, jack-in-the-hedge and tansy. We carefully tended our fine nettles (Gypsy spinach), and I planted an amount of the strange wild onion of the New Forest, establishing it around the roots of our apple trees where it likes to grow semi-wild and is found in quantities in many old orchards, apart from growing quite wild along hedge banks, where I likewise planted it in our garden.

My children and our hound all ate the wild garlic in quantities with much enjoyment, and we were not alone in our liking for it. Many of the foresters also sought it eagerly, and the forest ponies and cattle ate up all which came within their questing reach.

Forest ponies and cattle! I was well able to protect my crops and flowers from the birds, small field animals and insects by using the powdered herbs, but could not attempt such use against the ponies and cows, which, well aware of my quantities of long grass beneath the apple trees and the many shrubby things of my garden, likewise the good stretches of vegetables, lingered much around our gate seeking opportunities to break in if anyone closed it carelessly or forgot to close it at all.

All around one heard of damage done; and the cows were quick to follow the plundering of the ponies. I put scythed grass and windfall apples outside our gate for the ponies, only they still broke into my garden. More and more the ponies are getting into forest gardens. The unwise and unnatural petrol-spraying and then firing used in the New Forest by the authorities have destroyed large amounts of the native herbs needed by the grazing animals, from pony to deer, to vary their diet and keep them healthy. The reason behind the artificial burning of large tracts of forest land was the destruction of bracken and gorse which might at some time endanger the valuable tree enclosures if at any day the gorseland should burn more naturally without the assistance of petrol spraying. It was also claimed that the burnings produced young growths of heather and gorse to feed the commonable animals, and especially feed the ponies. But we naturalists, who walked in the forest, saw that deserts of rank bracken grew where formerly there had been a variety of wild plants, including the healthful herbs, and we knew that countless birds died also in the sudden artificial fires. The ponies therefore were being driven into the gardens and smallholdings; and I seemed to get an unfair proportion of them in mine!

Having gained entry into a garden, the ponies quickly ate up every vegetable within reach of their powerful jaws, furthermore uprooting and crushing as they devoured. They well understand the health virtues of raspberry canes, especially the in-foal mares who seek them in place of the destroyed brambles which they need, and all know the health riches in the onion plants which are usually amongst the first that they take; they certainly quickly took most of mine. They trampled heedlessly shrubs and flowers, especially the fragile growths of spring bulbs, and left deep hoof marks on lawns. Then when they were discovered by the garden owners, they would make an always stampeding exit, with more plants trampled under running hooves and shrubs broken by bodies forcing through them.

The worst of the forest cow trespassers in our area was the Witts’ cow, Dolly. But as she was owned by friends of ours and we had much of her delicious butter, which had the rich golden colour of the marsh marigolds of the water meadow below us, we had to accept her visits, but do all possible to prevent them! Dolly’s need seemed to be ivy, of which we possessed quantities. The big red cow knew where to find the best ivy in our garden, but sadly for my plants, always made her way there across the herbaceous bed, and her hurried way out again also, when she was being chased by me or our hound.

Concerning Dolly’s liking for ivy, and similar liking of cows, a wrongful statement concerning cows and ivy was heard on the wireless, whilst I was at Abbots Well. The speaker told of a sick cow which had been beyond hope of saving. But the cow had got out of the stable and had sought ivy and recovered from her illness. The speaker had then gone on to say that ivy was poisonous to cows.

I was worried at such misstatement, for I know ivy to be one of nature’s finest tonics for the herbivorous animals, especially as a cleanser after giving birth, its only adverse property being that it is rather astringent and could lessen milk production if eaten too frequently in large quantities.

Soon after that radio talk, I heard Lenn Witt approaching where I was working, scything grass. The forester’s footsteps were known to both my children and me, the heavy, dragging boots.

I called across the lane.

‘Hi! They’ve just said on the wireless that ivy is poison for cows! What do you think about that?’

Lenn Witt came across to me and rested one big hand on the gate and slapped his chest with the other, as if to push out the better his words.

‘Pysen!’ he exclaimed and spat into the lane, ‘’tis doctor!’

And that well summed it up, for doctor it is!

I meant to write to the wireless talks producer and correct the error, but as the speaker was known to me and liked by me, we having once met, I decided to let things alone, and therefore my protest went no further than Lenn Witt. I was also influenced by the fact of the mistakes that I myself have made and been thankful that no one had found them and corrected them before me!

Lenn Witt and the local Gypsies were amongst our most frequent passersby, but others came by from farther away of special interest. Two of such drove to our gate one summer day, our first summer at Abbots Well. A Gypsy man and woman came on their high cart, pulled by a much decorated forest pony, all brass ornaments and ribbons. The cart carried numerous boxes of plants, mostly annuals of the orthodox park-garden type in which I find no pleasure. But I was thankful to see a box of white alyssum amongst the collection, as I wished to make some purchase from the travelling flowersellers.

The woman wore a wide-brimmed black hat of typical old-fashioned Gypsy style, black and white spotted dress-blouse, and a wide and long green woollen skirt, like a holly bush, with her strong dark-stockinged ankles showing beneath.

The man was more gaudy, but seemed less pure Gypsy than the woman. His slate-coloured trilby hat of curly brim was adorned with a bright jay plume tucked in its band. His jacket was of checked design of many colours, and he had around his powerful neck a yellow and red Paisley-patterned scarf.

The couple halted their pony when I answered their call to buy ‘pretty plants’.

I asked then to be shown their alyssum plants and the woman brought the boxful down from the cart to me. And the price that she asked was cheap and the plants so bushy and honey-scented – with my bees already winging to it like gay children joining in the fun – that I purchased the entire box.

The Gypsies then tried to pursuade me to buy more of their seedlings, of kinds which I do not like, but I was firm in refusal.

I felt that so much talk from the man and woman must have made them thirsty, and I had Rafik bring them mugfuls of the ice-cold water of Abbots Well, which always has the cold feel of the deep rock within it, and the child was very pleased to do that, he and his sister enjoying the visitors as much as I myself.

Then it was that the Gypsies saw our Afghan hound as she ran at the child’s side, as always busy protecting him, and they declared, enraptured, that they had never known before that such a beautiful dog existed in the world.

I told them that I had had fifteen of the kind once, and that Tullipan was the descendant of a strain of Afghan hounds which I had raised a while ago when I was little beyond school age, a strain of hounds which never knew disease.

They asked me to keep a puppy for them whenever Tullipan had any. I said that I would do so, and then pictured myself possibly handing the Afghan puppy over my gate to the Gypsies in exchange for several boxes of alyssum plants! That would not be the first hound of mine which had gone into the good hands of Gypsies, who usually know well how to rear an animal, be it horse, greyhound or fighting-cock.

When the travellers were ready to drive away, I asked them from where they came. And the woman replied:

‘From No Man’s Land.’ That then seemed to me to be perfection! The two Gypsies coming like that down the forest lane with the plant-laden cart to sell me flowers for my garden, and coming out from No Man’s Land.

It was not until a while later that I learnt that No Man’s Land was not some strange Gypsy region beyond the setting sun, from where the Gypsies are said to have come, but a real place on the New Forest border in the Wiltshire direction.

*

With an introduction by Megan McCubbin, ‘Wanderers in the New Forest’ is published on 7th March. Buy a copy here (£15.00).