From The Border Hills: Alistair Fitchett on a year spent falling in love with the landscape of the Scottish Borders through the books of D.E. Stevenson and Molly Clavering.

‘Old age really must be creeping upon me at last. I find more and more that what I most enjoy is a quiet evening at home by the fire, with a book.’ – Molly Clavering, Touch Not The Nettle.

The Scottish Borders has long been, for me, a land to pass through on the way from here to there and back again. At first, by car with my father behind the wheel, then by train and finally again by car, this time driving myself. Going to somewhere and home again, and eventually vice versa. Places I would know only by railway stations and road signs pointing off the M73: Ecclefechan, Lockerbie, Beattock, Moffat. Then into the edges of Dumfries and Galloway with Abington, Elvanfoot, Leadhills and The Mennock Pass, which I think of as less Borders and more edging into Ayrshire and onto the dark, neglected former mining villages with guttural names. Glespin. Muirkirk. Sanquhar. Ardoch. Places where Scots meets Klingon.

Then I read D.E. Stevenson and Molly Clavering, both of whom settled and worked in Moffat during the interwar years and post-WW2. From there they turned out book after book of romantic fiction which were often set in the Borders landscape and, in Stevenson’s case particularly, proved to be enormously popular in their time. I first stumbled into their world in the latter months of 2022 via Stevenson’s Miss Buncle’s Book (broadcast throughout December 2023 on BBC Radio 4) encased in the beautiful grey covers of the Persephone reissue imprint. Many more of Stevenson’s impressively sizeable catalogue (she penned over 40 books in the space of as many years) are available again through the Furrowed Middlebrow imprint and these in particular have been a source of enormous pleasure to me throughout 2023, with the second two thirds of her Drumburly trilogy (Music In The Hills and Winter and Rough Weather) making for a tremendous evocation of the Borders landscape.

With these two novels Stevenson indulges us with some tremendous evocations of place, where the imaginary Drumburly and Mureth are amalgams of aspects of the Scottish Border country that the author, whose father was a first cousin to Robert Louis Stevenson, knew and loved. Whilst many of the place names are fictitious, Dumfries and Lockerbie are both mentioned, as is Gretna Green, to which of course a closeted 14-year-old girl who falls in love with a man twice her age talks about running away and getting married. It’s a nice nod to historical fact and to the tropes of Historical Romances, which, through the passing of time, Stevenson’s novels have become.

At their heart the books deal with notions of a woman’s place within a man’s world and if the views expressed are essentially conservative and traditional then at least they are contextualised within the period. Some might balk at it all regardless, of course, and that is fine. But one does not need to agree with statements to understand them, surely? Anyway, central to the books is artist Rhoda who makes the point that ‘If I married I could go on painting as a hobby but not as a career. It’s different for a man. A man can do the thing he’s good at and be married too. A woman can’t.’ Or can she? One might struggle to call Stevenson a feminist, but she is at core an optimist, and whilst nothing particularly shakes the traditional expectations of the period in her books, she does like most of her characters to Live Happily Ever After. Her novels, like most Romances after all, are essentially fairy tales for grown-ups and there is not much wrong with that.

Whilst D.E. Stevenson’s books sold in terrific numbers, her great friend Molly Clavering’s, whilst hardly unappreciated in their time, nevertheless sold significantly less. It is perhaps then even more gratifying to have many of her books available once more, also through the Furrowed Middlebrow imprint. Of these, the utterly delightful Mrs Lorimer’s Quiet Summer may well be the best. First published in 1953, this is another of those novels that prickles lightly with post-war austerity and the sense of Life Returning To Normal, where Normal is something altogether Different. There is less of the sense of that new age being as discomfiting for the Middle Classes (as the characters in the book most assuredly are) as there might be in other post-war novels, but that is fine, for it is hardly positioned to make Serious Points about society, people or anything else. Rather, it is an unashamedly light-hearted book that giggles and glistens in the sunlight, unafraid to unravel its threads into occasional trip hazards in its relentless and joyous pursuit of pleasure.

The novel is to a degree autobiographical, with Mrs Lorimer appearing as a thinly disguised D.E. Stevenson, and her dear friend Grace Maxwell co-starring as Clavering. The portraits of both women are warm and quietly admiring, and if one might arch an eyebrow and suggest that Clavering has been particularly kind to herself then by all accounts the depiction appears to be accurate, for contemporary descriptions have her as a figure with a marvellously positive outlook and a cheery disposition. Notable dissenters to this opinion at the time of the book’s original publication were Stevenson’s children, all of whom are necessarily given at least one prickly character trait that Clavering teases at and weaves her narrative around. By all accounts the irritation did not last long however, and that is no real surprise, for all the little nuances are really genre-related literary devices.

If the interminable raking over of history to be found in Serious (i.e., non-genre) Literature is the kind of thing you enjoy then I dare say that Mrs Lorimer’s Quiet Summer would be sniffed at in distaste and left untouched on the shelf. Whilst understandable (we each of us have our Points Of Interest and Areas Of Pointed Ignorance, after all) I cannot help but suggest such an attitude would be a shame, for Mrs Lorimer is one of those wonderfully undemanding novels that romps along with a deceptively easy step, every so often dropping a line or two that, whilst not exactly shatteringly insightful into the nature of existence, nevertheless causes one to nod sagely. The more so, I expect, if one has reached the same sort of age that Clavering was when writing (53, since you ask). There are, in particular, some lovely observations on the process of maturing, or not, and when Lorimer/Stevenson reflects ‘…what a silly little fool one was at twenty-three’ and Douglas/Clavering responds with ‘Most of us were. Some of us still are. It’s a safeguard to realise it…’ one rather hopes that anyone of a similar age or older will recognise a universal truth lightly proclaimed. I know I do.

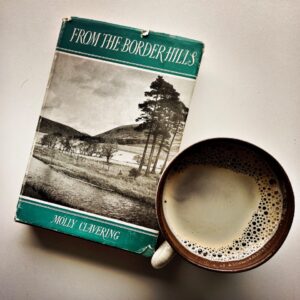

Modern readers on the whole, however, may find Clavering’s non-fiction From The Border Hills to be more to their taste. Published in the same year as Mrs Lorimer’s Quiet Summer, it amusingly starts with what I imagine is a telephone conversation with Stevenson, in which Clavering declines an eleven o-clock coffee in town in favour of a day’s walking up Moffat Water. For the next 15 chapters Clavering leads us on a marvellous tramp through the landscape, mixing local history and folklore with literary references (notably Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott). Gratifyingly too there is space for Clavering’s own voice to come through, and the book very much reads as a homely, personal adventure in which the pleasure of discovery, knowledge and immersion in landscape is shared. The book, sadly, has never been re-published since its appearance in 1953, but is well worth looking out for in second-hand bookshops.

Since reading Clavering and Stevenson in 2023 (twenty books, and counting…), then, I have willingly detoured on a couple of my journeys between Devon and Ayrshire to take in some brief mooches around Moffat and its environs. Each time I have been seduced further by both the landscape and the ghosts of those two authors’ works. In 2024, whilst I am sure I shall continue to enjoy ‘quiet evening(s) at home by the fire, with a book’, I also have half a mind to spend more time there, and, armed with my copy of From The Border Hills follow further in their footsteps. Perhaps this time next year I shall let you know how I got on.