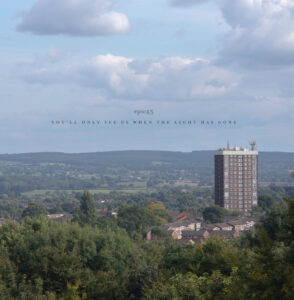

On epic45’s recent record ‘You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone’, beauty is in the everyday and God is in the mundane, finds Alistair Fitchett.

The sight of the sun going down may no longer make me cry but the passing of things into darkness certainly brings a chill of melancholy. This is the inevitability of age of course, as inescapable as the cycles of nature. Things end. Things begin. Blink and you miss them.

Much of this is captured in You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone, the new, and perhaps the last, record by epic45, an artist I first came across back in 2002. The introduction was via Anthony Harding and his July Skies project, whose remarkable Dreaming Of Spires LP I was fortunate enough to write about for Careless Talk Costs Lives magazine. For me that record was like opening a doorway into a secret garden within a secret garden, a strange space inhabited by those eking out artistic existences beyond the reach of even the ‘underground’ never mind the mainstream. This was a realm of small country churches and derelict WW2 airfields. OS maps and the tracings of Beeching’s vandalism. Electricity pylons marching through forests. Ladybird books, Lone Pine paperbacks; the illustrations of Robert Lumley and Bertram Prance. Peculiarities at the end of the 20th Century.

Not quite so peculiar now, perhaps, as many of these infatuations have become more readily accessible in the intervening two decades thanks to the sprawl of the Internet and social media. Yet there remains something appealing and slightly Other about them. Profoundly analogue, perhaps, even whilst propagated and experienced in digital arenas. There is something of nostalgia at work, certainly, but equally certainly nothing so stultifying as a preoccupation with the past. This nostalgia is instead about drawing emotional strength, synthesising knowledge and experience into something new. The creative process (and the learning process) in a nutshell.

That nod to The Field Mice in the opening line here is apt too, for there are surely some shared points of interest and influence at work between epic45’s Ben Holton and Bobby Wratten of The Field Mice, Lightning In A Twilight World and others. Something to do with a certain kind of oddly assured fragility that casual misinformed cynics might wrongly classify as limp or fey. A fascination with the temporal distortions of liminal spaces, both physical and psychic. Spirits in their houses, ghosts in their machines. Usborne’s books on their childhood bookshelves. Things we all invent and project on our eyelids to make sense of what we feel around us. Music, photographs, words. Whispers or whatever.

Musically, it is certainly possible to listen to the thirty two minutes of You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone and to hear echoes of the likes of The Field Mice or Sarah labelmates Blueboy, more so perhaps than on any previous epic45 record. Album opener ‘New Town Faded’, with its humorous nod to a Joy Division title, could be the kissing cousin to something from the delicious Unisex album, for example; ‘Be Nowhere’ an amorphous echo of the lilac 10” sleeved ‘Snowball’. If such comparisons make you shudder then that is most likely your loss. But then again we all blink and miss something sometimes.

There is also, in the music of epic45 and also throughout the nigh-on-20 year existence of Holton’s Wayside and Woodland imprint, a fascination with suburbia, for there are few more liminal spaces after all. Tracey Thorn has written eloquently about suburbia in her Another Planet book of course, but she would likely agree that her heart was always in the city with the suburbs as something to escape, a place and a set of feelings to leave behind. Fond memories, perhaps, but only in hindsight and only with the weight of age to temper their adolescent frustration.

It is perhaps inevitable that anyone with a creative impulse would feel constrained by suburbia, its insistence on uniformity apparently the enemy of individual expression. Yet it is not necessarily the case. Artist John Myers spent most of the 1970s making photographs of the “garages, TVs, electricity substations, new builds and [his] neighbours” in Stourbridge. Collected in the 2017 book The World Is Not Beautiful, Myers’ photographs in fact suggest just the opposite. Beauty is in the everyday and God is in the mundane. In the work of epic45 there feels something of the same impulse. An embrace with suburbia where both parties naturally hold each other a little distantly. It wouldn’t do to be too familiar, would it? Holton, like John Myers is a recorder, making notes on the spaces he exists within and passes through. This is done musically of course, but in recent years it is increasingly also through photography, much of which finds place within printed books supporting the sounds, an excellent alternative means of giving physical artefacts to digitally distributed music.

There is an acceptance too, in the work of Myers and of Holton, I think, of the tension inherent in suburbia. These are spaces that by definition look both inwards and outwards, forever ripped and torn by duelling impulses that create a certain kind of neurotic anxiety. Agatha Christie recognised this in her 1969 Poirot novel Hallowe’en Party, a book which Kenneth Branagh made almost unrecognisable as the 2023 film A Haunting In Venice. Christie’s writing in the novel may be a long way from her finest, but although there is a distinct clumsiness about everything in the book, Christie does at least recognise the sordid repression of suburbia and the incipient mental health conditions it might generate.

It is this duality of existence that epic45 capture in the closing track on You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone. A six minute post-shoegaze, ahem, ‘epic’, called, appropriately enough, ‘Finality’, the song suggests movement and stasis at the same time. Travels to find “another place, another town” are plagued by both the disappointment and relief at finding them all the same. Suburbia being by default about uniformity. Everything is nowhere and nothing is everywhere. You can hear the echo of adolescent anger in the almost buried, shouted, vocal that counterpoints the same electronically treated sung lyric. It is both heartbreaking and oddly celebratory, like the work of David Lynch or the peculiar surrealism of Skids’ ‘Sweet Suburbia’ whose single sleeve oddly predicted New York anglophile band My Favorite’s ‘Detectives of Suburbia’. 17 years and an ocean apart. What was that about nods, whispers or whatever? Blink and you miss them.

You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone then is a punctuation mark in the creative journey of Ben Holton and epic45. A period perhaps, but only time will tell. It may unfurl in the future as a semi-colon, an elongated pause for breath before another plunge. One certainly suspects that even if this record sees the ‘end’ of epic45 there will be future Holton projects. His ‘Twelve Months’ work of music and photography as Birds In The Brickwork for example is already at volume three and must surely promise more. I admit I have not purchased the accompanying calendars (like most of the limited runs of physical artefacts from Wayside and Woodland, they tend to sell out quickly), but the cover image for the 2023 edition is thoroughly entrancing, like a West Midlands suburban Todd Hido outtake from House Hunting or Robert Adams’ Summer Nights, Walking in Water Orton instead of the Colorado Front Range. Looking for the echoes of Lawrence and Maurice Deebank rather than Emily Dickinson. Crumbling the antiseptic beauty, indeed.

You’ll Only See Us When The Light Is Gone is out now on Wayside and Woodland. Don’t blink. Don’t miss it.