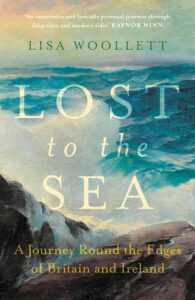

Soon to be published by John Murray Press, Lisa Woollett’s ‘Lost to the Sea’ explores where mythology and reality meet on Britain and Ireland’s margins. Its author has an eye for detail, finds Tom Bolton — and for the strange, the inexplicable, the funny and the unforgettable.

Britain is falling apart. Ireland is crumbling. From the far north to the deep south west, the coast is retreating and realigning, constantly on the move. This is not a new phenomenon. It is easy to forget that the current shape of the British Isles, imprinted in our minds, is just the way it looks now. In medieval England and before, great chunks of the land we now inhabit were missing. The Wash extended inland as a great bay, submerging the pre-drainage Fens. The sea extended long fingers into the Norfolk Broads. Long-silted estuaries made Rye, Tenterden and Winchelsea ports. The Somerset Levels spread a lake around the Isle of Avalon. But the coast has pulled back as much as it has expanded. Towns and villages have been dragged apart, excruciatingly and inevitably, by the sea and pulled down into the murky depths.

The reshaping of our coastline is entangled with tales of lost lands re-emerging from the waves, churches on the sea-bed, their bells inevitably still ringing, and places that may have once existed, or may not. Origin myths abound in our occluded seas which, dark with sediment, keep archaeologists at bay and create space for multiple versions of the truth. Lisa Woollett’s Lost to the Sea is an absorbing account of her travels around Britain and Ireland, looking for vanished and vanishing coastal places: from those that are known only through mythology, to those we can observe falling into the sea using the Google Earth Pro history function.

Woollett also visits places on the climate change-eroded edges of Britain, some well-documented and others much less well known. The villagers of Fairbourne, in Gwynedd, to be ‘decommissioned’ by 2054, have been described as the UK’s first climate refugees. The erosion of sea defences that keep their homes viable has been accelerated by rising sea levels and more frequent storms. Woollett, however, also places their story in the context of a long process of change that has left the prehistoric trees of Borth Bog preserved under Ceredigion Bay, emerging at low tide as a ‘dark, fairy-tale world’. Once known as “Noah’s trees”, they are evidence of a great inundation that probably submerged three Welsh islands. Flood stories abound. Lost to the Sea uncovers similarly fascinating stories linking the myth of Lyonesse to parts of the Scilly Isles that can still be seen just below the surface; locating the lost Isle of Fitha off the Galway coast; seeking the elusive Ravenser Odd off Holderness; and probing the sand dunes of the Aberdeenshire coast which buried the village of Forvie.

The book combines deep history with an insatiable curiosity about what is happening on our coastline right now. Woollett’s expeditions are defined by physical reality, and her writing neatly combines her extensive and impressive research work with the process of travelling to the far north of Scotland, persuading a boatman to take her to an unvisited island…and to pick her up again…or scrambling down abandoned coast paths on the Isle of Wight. The coast is retreating dramatically in places such as Happisburgh, in Norfolk. I am often drawn back to the Hill House Inn, where relics of Arthur Conan Doyle, who wrote a Sherlock Holmes story while staying at the pub, and literary legend Lorna Sage, hang on the walls of a 16th century pub that sits within the 20-year coastal retreat zone. Woollett tracks the astonishing discovery in 2013 of fossilised footprints on Happisburgh beach, revealed by erosion, which placed ‘humans in Britain at least 350,000 years earlier than previously thought’. She also walks the fragile Happisburgh clifftop, recording the terracotta drain pipes protruding from the cliff face below an abandoned campsite, and metal stairs that once led to the beach, and now lead nowhere.

Lost to the Sea contains clear, well-written explorations of the fascinating interface between history and mythology. However, it is Lisa Woollett’s own enthusiasm and eye for detail that make the book more than the sum of its parts. She has an excellent sense of the strange, the inexplicable, the funny and the unforgettable. Favourite moments can be found throughout her highly enjoyable enquiry into our edges. They include Jer de Bull, herder and fisherman, the last man to live on Mutton Island, Galway, who flew a red flag when he needed anything. There is the terrifying process of “dune blow-out”, when the marram grass anchoring a sand dune is undermined by winds and the dune becomes a sand cloud that can, and does, bury villages. There is the Broadstairs landlord who claimed his ‘oaken shuffleboard’ was made from a tree that grew on the legendary Isle of Lomea, in the Channel. There are the women of the lost fishing village of Old Hallsands, in Devon, who carried their husbands out to their boats on their shoulders so they could start the day dry.

Woollet does an excellent job of exploring the margins, and weaving a wider story around disparate times and places. She evokes the sadness of places that lost their futures and tells stories that are not yet concluded, and will in time melt into myth. Lost to the Sea is a fascinating and alluring book, and it explores stories we would do well to remember.

*

‘Lost to the Sea’ is published on Thursday and available here (£19.00).