Artist Sam Francis takes a firm, spiky hold of the Nettlecombe estate’s namesake plant.

First, be bold, as to be timid is to be stung. Practice a firm pinching motion with your thumb and forefinger in the air so that you feel a slight pressure between your fingertips when they meet. Test it out with something light and thin like a corner of a newspaper. Then, progress onto a non-stinging plant that you are prepared to sacrifice a leaf of. With a swift, sure movement grab the leaf around the centre of its blade between your fingers. Be sure to approach the leaf from its base, moving towards the tip in the direction of growth of the nettle’s hollow stinging hairs, as to move from tip to base is to suffer. Once contact has occurred, pull gently yet firmly until the petiole breaks the leaf away from the plant’s main stem. Stay vigilant. Release the leaf in an equally swift movement so as not to get caught out at the last moment.

You are now ready to grasp the nettle.

I’m sitting around the back of a tumble-down artist studio at Nettlecombe. Shorts on, shoes off, basking in the spiky June sun like a lizard, surrounded by towers of nettles. My ankles and neck fizzing with little stings. I do not yet know how to grasp a nettle without getting stung.

I first encountered Nettlecombe by chance. Finding ourselves with time to kill after a weekend in Exmoor, my companion and I follow the brown road sign that indicates places of interest to visit for leisure and pleasure, pointing to a cider farm. We drive down the long, grandiose driveway with its nettley verges, duck ponds, momentous copper beech trees, sweet chestnuts, and towering bamboo leading to Nettlecombe Court — an Elizabethan manor house (now a field studies centre) nestled into the crook of a small valley, surrounded by undulating parkland, stippled woodlands, and a twelfth century church. Wandering away from the main house, up the pot-holed track and through an ancient lichen-laden sessile oak grove, the atmosphere shifts. We discover a Palladian-esque courtyard; the walls seeped in the moreish-ly textured, dusty apricot-pink pigment of West Somerset’s rich red earth. There are no apple orchards to be seen. Curious, and uncertain if we should be here, we tentatively look about, wondering what this place is. The assortment of slightly ramshackle buildings, barns, cottages, stables, sheds and store-houses dotted around the courtyard are spilling with clues. I have been places like this before with imperfect edges, where the colour of things veers into a different tint. Shades of a place that hints of a particular spirit. Nameless stories rising out of the ground. Places on the sidelines, where their original purpose is a thing of the past. In this case, a place within a place where once the gentry, land, and animals would have been serviced from. Now transitioned into a new place where other-than things occur.

There are clues in the air of it being a special place; an-other place. I can smell counterculture wafting from the flaking paint of the wonky door frames. I have a nose for such things.

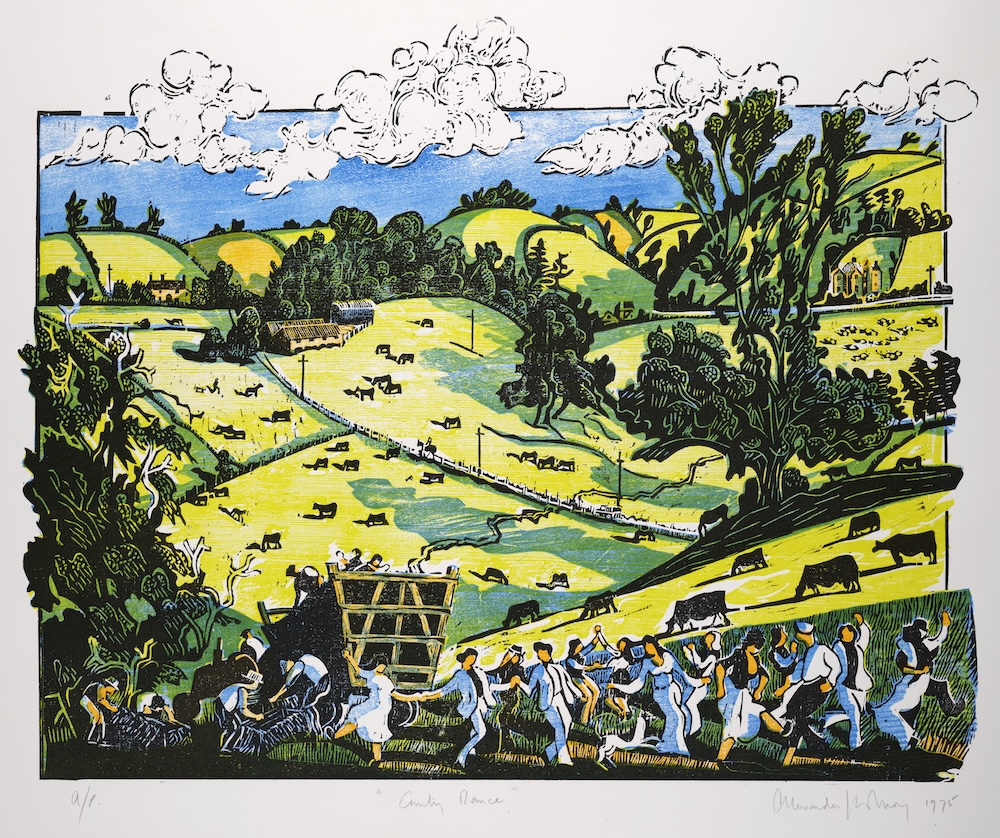

The studio I’m sitting outside is brim-full of the work of artist Alexander Hollweg — incidentally the grandson of acclaimed vorticist painter Edward Wadsworth — who lived and worked at Nettlecombe from the mid 1970s until his death in 2020. From the late 1960s, an artistic and creative community began to form at Nettlecombe through artist John Wolseley, the latest inheritor of the hundred-and-fifty acre estate. The cheap possibilities of space and rural life were appealing to artists, makers, and writers; dreamers keen to escape the restrictions of costly, close-quarter city living. Hollweg’s pastoral woodcut relief print ‘Country Dance’, which is in the Tate collection, at first viewing depicts an idyllic country scene, where this new loosely-formed community and the land’s labourers co-exist in some form of rural harmony, celebrating the hay wain in a nod to Constable’s painting that the artwork was created in response to. Yet it is what lays beneath this simplistic portrayal, and the contrary realities of working a landscape where fields must be ploughed and straw baled — alongside how a community of artists exists within the contrasts, conflicts, loves, lives, dreams, and messy realities of country living for the past half-century — that really interests me.

‘Country Dance’, Alexander Hollweg, 1976

This is why I’m here. To respond to the place, its lost time, an artist, a single artwork. It is not the first time I have been here in such a way. In 2022, I was invited to respond to another artwork; a ‘fabric performance’ piece from 1980 called ‘Year in the Life of a Field’ by artist Lizzie Cox (1946-2011) who lived at Nettlecombe for a decade from the late 1970s. Throughout that year, and marked by the solstices and equinoxes, I visited this field to attempt to get to know of it. To commune with its seasonal changes. I wrote a series of field reports, hand-made a book, and a new film work from my interactions with the field, in dialogue with the artwork and the life of the artist. And now I find myself drawn back to this place again. It is not lost on me that I seem to have become an artist who responds to places and artists who themselves have made work that has responded to the place I’m responding to. Like the wheel of the year; a continual cycle of responses responding in response to a response. It’s all rather meta.

Nettles, nettles everywhere!

In this valley of nettles it goes without saying that they are wildly abundant. They cluster around the edges of things; pathways, fences, treelines, thickets. Outliers, they thrive on the sidelines keeping an eye out for trouble like a protection racket. It is no longer a prim-kept, manicured place for the gentry; it is a place for common things, for regular and irregular folk, with its multi-varietied orchards, and throngs of nettles here and there. Nettles thrive in phosphate-rich soil found where humans have settled. In places where people gather and come together, in this case, a community of artists. Seekers of alternative ways of living and being forming a congregation of creative liveliness, for a mere moment in the long history of this place.

Where nettles grow, people go.

Nettlecombe gathering, c. 1980, from the Hollweg family archive

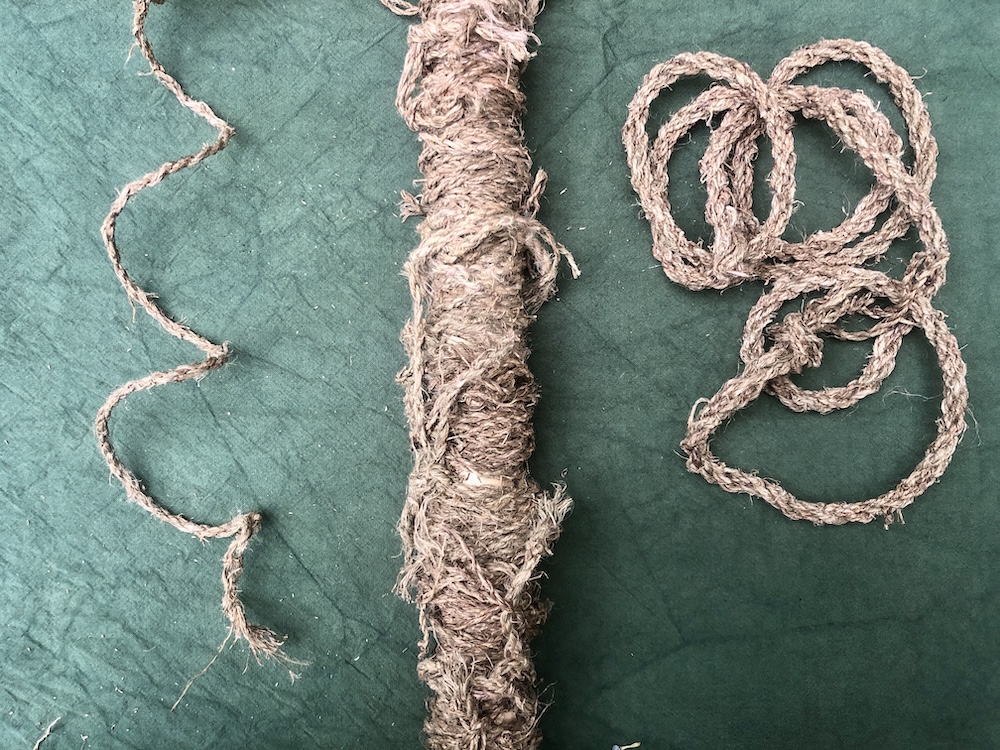

Gloves on, I lean into the dense bushes of nettles with their ankle-grazing stingers and green spears lurching into the sky. Nettles can grow up to 8 feet tall — taller than the tallest human — and these are the ones that I want and go in for, snipping off a few stalks near to the root base with rusty secateurs. I get stung on the neck several times, leaving me with a nettley love bite. In a long swift downwards motion I strip the leaves from the stem, rendering it stingless so I can now remove the gloves; though the leaves remain stingy until wilted either through means of immersion in water, or simply leaving to the will of the sun, air, and time. I start to try and work out how to remove the pith and strip the strings from the stem that will then be dried, then scutched, then twisted into the twine that will eventually make the cordage I am having a go at making. Nettle cordage and twine is an essential survival item, and the use of natural fibres is of course rooted in deep history. Cloth made from nettle fibres makes hard-wearing fabric, and steeping cloth in strained nettles gives various shades of camouflage — though my future experiments turn out to be a murky palette of near-brown tones. I don’t yet know what I am doing or why I am doing it, or where it will lead, or what it may become, or how I may use it, but I have a sense that not knowing is part of the process that I need to go through in order to make any sense of the what and where and why and how of what I will ultimately create for this project.

The many-parted process of cordage-making insists upon slowness. The continual actions that make up the activity — the gathering, the sitting, the constant movement of the hands, the clumsiness of un-dexterous novice fingers that will eventually find their rhythm with the fibres — all offer up room for the mind to be spacious and enlist in the silent doingness of thinking. To mull over and pay attention to all that is to be discovered about this place both in a physical sense, and what has been, and is unseen. The Tibetan word shul means the mark or imprint we make on the land — like a footprint that leaves an invisible trace which contributes to the unique atmosphere of a place, more felt than seen. The locus solus of it. I feel a sense of responsibility to the people, the place, and the activity that has and continues to take place at Nettlecombe. I shall tread lightly upon it all.

Autumn. I head to Nettlecombe to stay for three months and immerse myself deeply in the place that will further shape ideas that will turn into the work that will form the exhibition I’m working towards making. I can’t see how I would create work that is about an uncovering, a revealing of place, a stripping of layers, of time and of twine, without being physically here and living it. And my status as a free, independent woman who is on good terms with relative solitude means that I can be. I’m staying in a domesticated shipping container with an outside kitchen, sky-lit shower, and compost toilet. If it gets cold I can always rub nettles on my arms and legs to help me keep warm as the deviant Romans were said to have done. My temporary home is situated at the top of the valley overlooking the cluster of out-buildings in the valley bowl below. It is wide-viewed and spacious up here and I’m glad for it. My mum comes for two days to help clear out the pig-shed to make it habitable for use as a temporary studio. It has been used as a studio before by jeweller Geraldine Hollweg — Alexander Hollweg’s wife who he shared a life with at Nettlecombe — so it already has the bones and air of a creative work space. We fill cracks and gaps, move on the community of spiders who have made it their home, white-wash walls, string power from an adjacent building through the scratchy brambles, get rid of all the junk stuff that gets dumped in such spaces, light incense and chuck lemongrass oil about to mask the smell of damp. We try not to hit our heads on the made-for-pig-height door frame. The pig shed is surrounded by nettles that I am reluctant to clear and so must pass through a nettley realm on my way to the studio, which feels right somehow.

On stinging. The latin for the Common Nettle is Urtica dioica. It derives from the Anglo-Saxon word noedl meaning needle, while its Latin name urtica means to burn. I have come to get used to the light buzzing and bumping of the skin that can sometimes last all day. The widespread historical use of nettles in various medicinal forms are said to temper the pains of rheumatism and arthritis. Urtication encourages the sufferer to gather a bundle of nettles to lash the painful area for ten minutes (not too hard) — either by self-flagellation or by another, which may have elicited the fun nettle alt-name of ‘Naughty Man’s Plaything’. I discover an old pamphlet in this name by naturalist Roy Vickery, who I contact and who kindly posts one to me from his home. It contains wild tales and tall stingy stories from across the British Isles of the nettle’s uses and folklore. ‘Unspoken nettles’ gathered at midnight are a cure for the long-term sick. To carry a sachet of dried nettle with you will remove a hex cast upon you. While at the World Nettle Eating Championship taking place in Bridport, Dorset each June ‘the trick is to roll them up in a special way with the tongue, making sure that there is plenty of saliva to coat them’. I’m not brave enough to test this out even with a single leaf, let alone be a participant in such torturous sounding shenanigans, though I am looking forward to observing the spectacle of it some day.

Nettle cordage and rope

From up on the hill, I settle into the short days of the valley and drift into a reverie of nettles whose wilting clumps are now thinning out; stems thickening and darkening as the end of the year draws steadily in. I sit outside the container in the winter-chilled sun with my crow friends for company, and move my fingers with more ease now around the nettle fibres making thread that will become the cordage that will become part of something else eventually. I drink jugs of nettle tea with a twist of lemon, and think about labour. About art-labour, land-labour, manual-labour. I think about art-making, and place-making. About the old ways, the slow ways, and crafting. About community, and gathering. About stinging. About the relationships between all of these things as they rise viewless out of the land that I wander upon, my own steps leaving a small trace; a shul. I while away strands of time in this way, eventually twisting nigh-on one-hundred-metres of cordage; my finger-tips hard-skinned and splintered with shards of wintering nettle. Skin that has now long recovered. Skin that no longer avoids the non-optional tingle of the nettle’s magical sting.

*

Sam Francis is a North Somerset based artist and creative producer who writes. This piece connects with her recent solo exhibition ‘People Came for Tea and Stayed Forever‘, at East Quay, Watchet. She is available for nettle workshops and other stingy and non-stingy things such as responding to artists and places.

You can buy Sam’s booklet ‘It Were all Muck and Nettles’ here. Listen to an audio piece telling a collective story of Nettlecombe, with interviews gathered from family and friends of Nettlecombe past and present, here. Watch ‘Harvesting Scutching Rubbing Twisting’ — films of the cordage making process – here.

The World Nettle Eating Championship takes place on 22nd June in Bridport, Dorset. Naughty Man’s Plaything: a nettling workshop takes place at Supernormal festival, 2nd-4th August, Oxfordshire.

Find more information about Nettlecombe Field Studies Council / Nettlecombe Craft School / Stay at Nettlecombe.