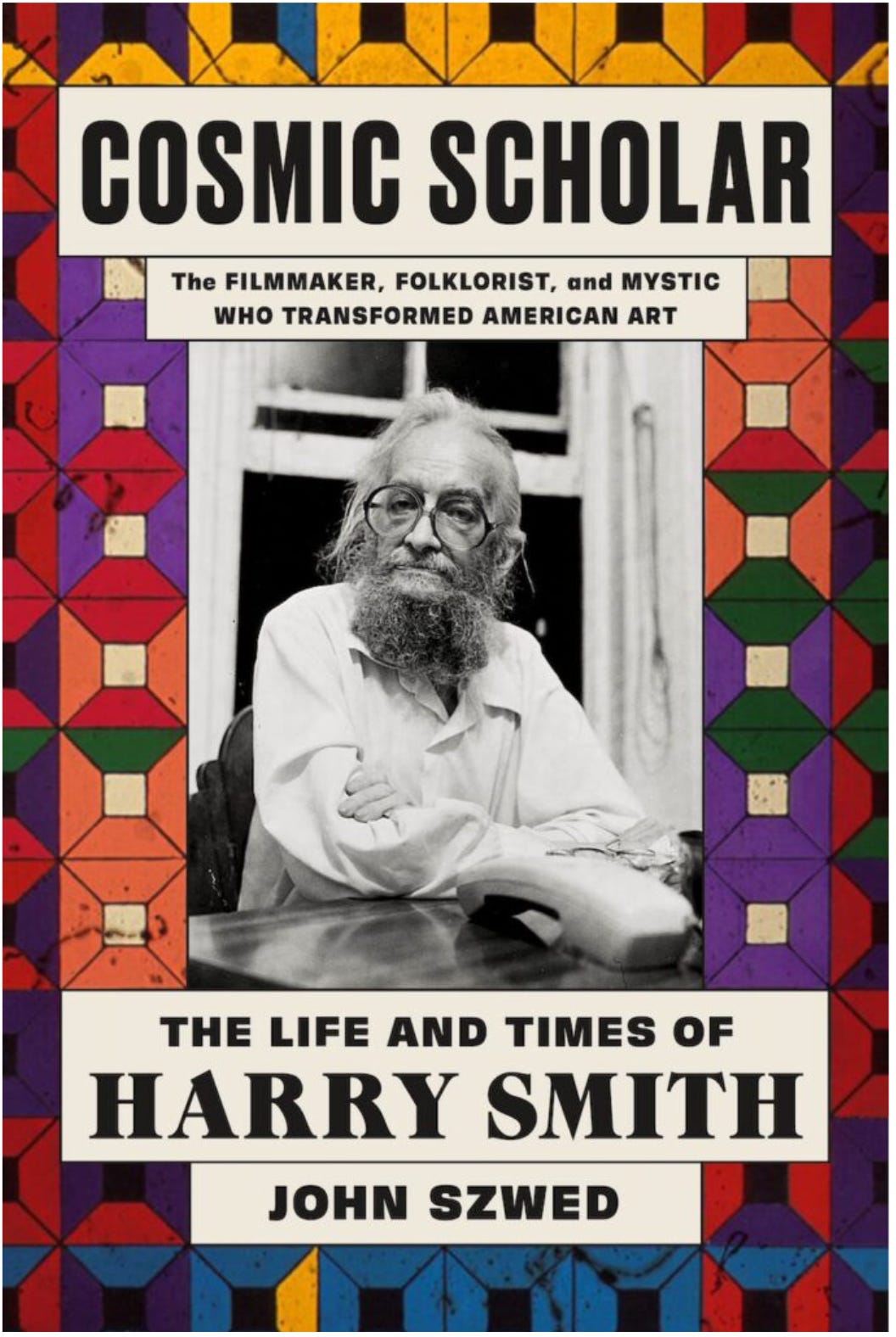

With a little help from biographer John Szwed, Andy Childs dives into the life and times of painter, filmmaker, jazz aficionado, multi-media artist, anthropologist, poet, folklorist, archivist, record producer, scholar, book collector, student of the occult, inventor, translator, hermetic alchemist and polymathic autodidact Harry Smith.

The role of biographer must surely be the most perilous and arduous one that a writer can assume. It’s self-evident that no biography can ever give a complete picture of a life or a life’s work, and memory is a slippery research tool, but the act of investigation, documentation, contextualisation and depiction, especially in the arts, has added immeasurably to our appreciation and understanding of how culture, as we now perceive it, has evolved. John Szwed has previously, and by general consensus successfully, tackled the lives of Miles Davis, Alan Lomax, Billie Holiday and Sun Ra so he’s no novice at untangling and illuminating the complex matrix of work, personal relationships, talent, character (inherited and otherwise), preoccupations, addictions and inner demons that constitute an important and enigmatic artist’s life. But as Szwed says in his introduction: ‘Though I thought I’d never encounter anyone as mysterious and undecipherable as Sun Ra, along came Harry’.

Until I’d read Cosmic Scholar I only knew of Harry Smith as the shadowy, eccentric figure who compiled the hugely influential Anthology Of American Folk Music. This is the 6-LP set of recordings, released in 1952 that inspired and provided material for a whole generation of aspiring folk singers, Bob Dylan famously included, and shaped the future of a significant strain of popular music for decades. The set consists of recordings of traditional, old-timey country, blues and folk songs that had never before been curated as a comprehensive overview of traditional American music. Such was its scope and academic thoroughness (Smith wrote copious notes for each selection) that many thought Harry Smith was a pseudonym for the great song collector Alan Lomax. Furthermore, Szwed calls the Anthology ‘the Rosetta Stone of music for the writers who were re-inventing popular music criticism’. Greil Marcus coined the term “old, weird America” to describe this music that for him was ‘a point of entry into an alternate, darker, and more complex history of the country’.

I had no idea that the man responsible for this milestone in popular music was also, at various times throughout his life (hold your breath) a painter, filmmaker, jazz aficionado, multi-media artist, anthropologist, poet, folklorist, archivist, record producer, scholar, book collector, student of the occult, inventor, translator, hermetic alchemist and polymathic autodidact. He has also been described as a natural fabulist, a shaman, a scrounger, crazy, evil, nasty, manipulative, destructive, abusive, and ‘a panhandling drunk, a frequently homeless polymath of the streets and the flophouses who could discourse sagely on any subject…’ In other words, a formidable challenge for even the most conscientious and even-handed biographer. That Szwed manages to successfully balance an exhaustive chronicle of Harry Smith’s unceasing inventory of achievements with an incisive, unsparing assessment of his character and an astute analysis of what made the man tick is a formidable accomplishment.

Smith was apparently always vague and inventive about his parents but we do know that he was born in 1923 in Portland, Oregon and suffered with rickets as a child which left him with spinal problems and gave him a slightly hunchbacked appearance as an adult. Partly as a result of this, his inability to take part in sports activities, and his precocious intelligence, he was a self-confessed lonely child. He read extensively from an early age and his latent creativity was undoubtedly nurtured and encouraged at an elementary school noted for its progressive education policy ‘focused on exploration and freedom of movement and thought’. Smith’s subsequent life is pretty much defined by these attitudes, indulging in and contributing to a phenomenal range of experimental arts and crafts. One of his over-riding passions as a precocious teenager was the study of the culture of the indigenous peoples of the northwestern U.S., an interest that led him to quit school in order to further his knowledge and later to study anthropology as a career. A “career” as such was never going to sit well with Smith’s restless curiosity and other preoccupations intervened: on moving to California he developed intense interests in avant-garde filmmaking, painting (which he considered some of the most important work he’d ever done, even though most of his art has been either accidentally or deliberately destroyed), and jazz. Perhaps Smith’s greatest talent was his visionary approach in combining these disparate interests to create forms that were fresh and innovative.

His abstract art was often an attempt to visually depict “the sound of music” for instance, and his films often incorporated bebop jazz. His talent for invention and artistic transgression produced the first ‘light shows’ in the late 40s, early 50s for a San Francisco jazz club — more than a decade before the celebrated light shows of the 60s San Francisco rock scene, and his life-long scrutiny of Native American traditions and immersion in ceremonial psychedelic drug culture resulted in a box set of 3 LPs on Folkways Records titled The Kiowa Peyote Meeting: Songs and Narratives by Members of a Tribe That Was Fundamental in Popularising the Native American Church — ‘a serious anthropological contribution, something noted by enthusiastic reviewers. Along with his paintings of course, Harry also thought his Kiowa research was the most important work he had done, and his record notes are the longest piece of writing by him that still exists’.

Smith’s film projects were equally complex, ambitious but frustratingly transient. His uncompleted re-interpretation of The Wizard Of Oz in animated form could and should have been a masterpiece of the genre, surpassing in scope and creative power anything that Disney had thus far produced, and his “collaboration” with Conrad Rooks on the drugs/Native Americans/ethnic music-themed Chappaqua, which won a Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival would, had its release not been delayed until 1967, been the first “trip” movie of the sixties.

Smith’s often belligerent behaviour however was, in the main, not conducive to durable artistic collaborations and so a lot of his film work especially remained unfinished. Also his itinerant lifestyle and his insistence that the act of creating art was more valuable than the resulting art itself meant that he adopted a somewhat cavalier attitude to finishing, preserving and curating his work. A great deal of what Smith created is now lost and dispersed — burnt, trashed, abandoned and discarded, which is probably why the enduring Anthology Of American Folk Music is what most people will know him for.

His extravagant expenditure on materials essential for his various artistic ventures and negligible interesting financial matters meant that Smith was always broke and in need of support. He was a notorious freeloader who nevertheless enjoyed the unquestioned beneficence of a number of people during his life; notably the writer and filmmaker Jonas Mekas and famed beat poet Allen Ginsberg. And when Ginsberg was unable to support Smith anymore, he approached The Grateful Dead’s manager about a possible grant from the band’s Rex Foundation. Forever grateful to Smith for the Anthology Of American Folk Music Jerry Garcia agreed to give him a grant of $10,000 a year. As influential as some of his work proved to be, official accolades were a rarity for a non-conformist outsider like Smith, but in later life he did receive a Grammy — a Special Merit Award, in 1991 — and that same year found him living at The Chelsea Hotel in New York, where he died the following year from bleeding ulcers and cardiac arrest, aged 68. That he’d lived that long was considered by some to be one of his greatest achievements. The speakers at his memorial service included Allen Ginsberg, Patti Smith and Dave Van Ronk.

I have in this review, you will deduce, only skimmed the surface of this enigmatic subject. Harry Smith emerges from this absorbing book as an impulsive, unwitting mover and shaker, half-mad genius, occasionally charming, often thoroughly objectionable, sociopathic, and yet as a result of his many achievements, able to command the respect and admiration of generations of musicians, filmmakers, artists and creative Bohemians. His life was a chaotic blizzard of obsessions pursued with a manic ferocity and a fierce intelligence but blighted by a self-destructive disposition that for the most part left him forever outside the mainstream of popular culture and without a comprehensive legacy. John Szwed does a remarkable job in re-positioning Smith and his work within the context of the cultural history of post-war America, and is a compulsive reminder that beneath the veneer of popular and homogenised social history that is thrown our way these days lies a neglected, profoundly influential world that is fascinating and deeply strange.

*

Published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, ‘Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith’ is out now in hardback, or available to preorder in paperback, out in September.