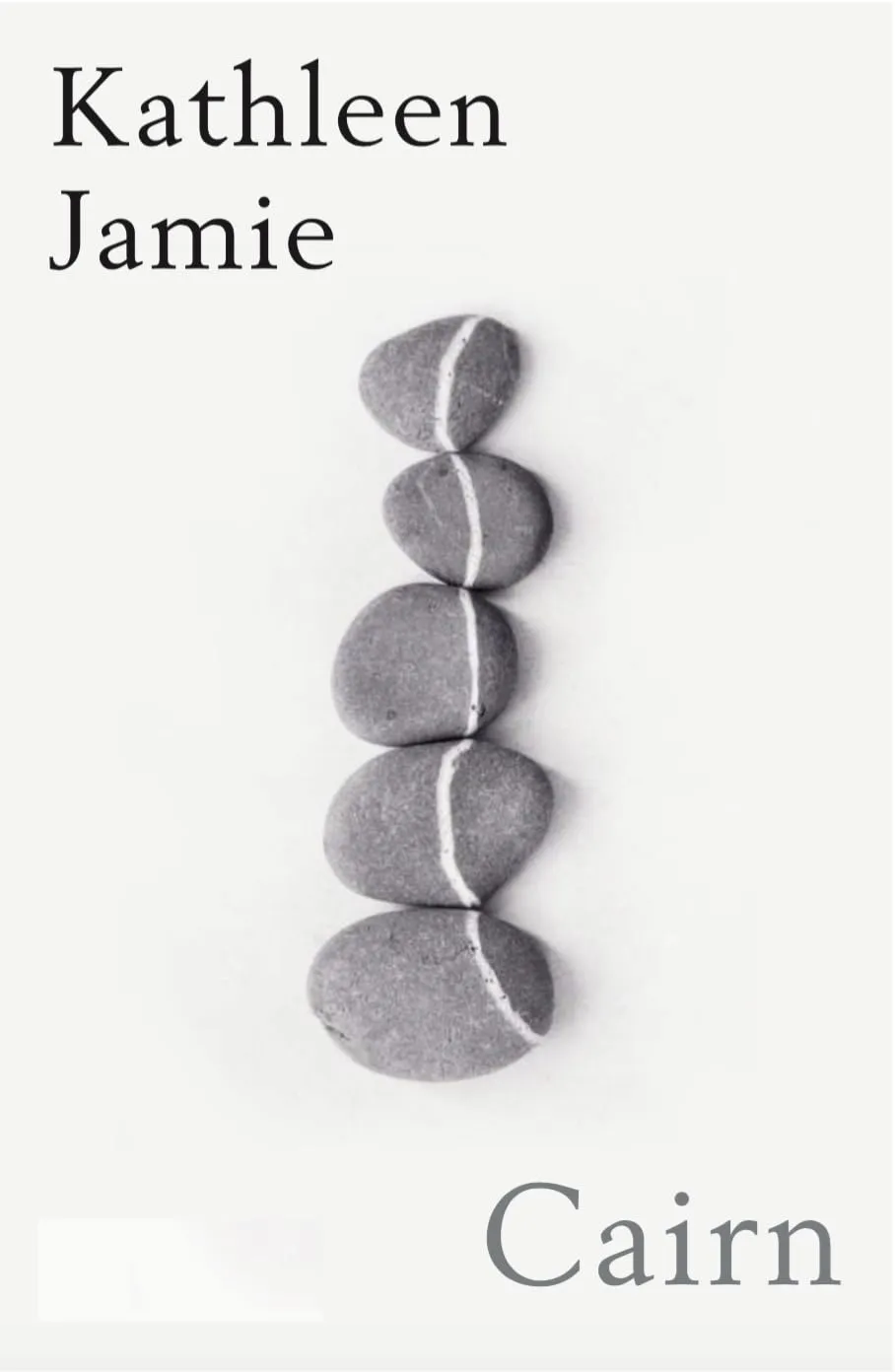

Kathleen Jamie’s ‘Cairn’ — a collection of micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments newly published by Sort of Books — is our Book of the Month for July. With its bursts of beautiful brilliance, it is something akin to lightning, writes Annie Worsley.

Over the years, I have found relief finding cairns in high places, along difficult mountain paths, and joy wandering around ancient cairns while puzzling at their making, their meanings. And I have placed small fragments of rock on stone heaps almost as a gift of thanks. For so many of us cairns are summit identifiers and landmarks, guides and way-makers on remote trails; they are memorials and burial sites. In every sense of the word, Katheen Jamie’s new book is all these things and more, actively and passionately.

Cairn is not weighty in physical terms; it is slim and light, but I stagger under its heft. Crafted from ultra-short essays, poems, and notes, its pages are filled with some of the most profound prose-poetry I have ever read. There are 137 pages of deeply personal pieces of writing gathered into a cairn of words and images.

In the same way cairns made of stone may be special, so too is this book. It is created from delicious fragments of thought, experience, feeling and acute observations, the kind of writing that Jamie does so well and for which she is so well known. Her acuity is special and here she turns her gaze and her mind to the peril and insecurity of life on earth, to the great natural challenges facing us all today and most especially, to her own sense of fragility and ephemerality.

Jamie’s previous books – Findings (2005), Sightlines (2012), Surfacing (2019) – brought nature writing into my life at a time when I was publishing my research in scientific journals. Here was a writer who not only described natural phenomena, she made explicit all the ordinariness of life, laying it out as part of a greater whole. I was reconnected to nature through her works when my own science had me looking dispassionately at physical earth systems and environments. As ‘nature writing’ bloomed, I could not see anyone like me amongst the descriptions of bravado and daring explorations in ‘wild’ places, but here was a woman explaining the nature(s) of the ordinary, the personal, of simply being.

Now Cairn has done something even more profound. Through small but interconnected fragments, the links between poems and prose, comes the realisation that we too are short-lived, tiny parts of an immense whole. When Jamie begins by saying in her prologue that the shape of her ‘life’s arc is becoming visible’, that no longer is life’s ending ‘beyond the horizon’, I cannot fully express, as a grandmother several years older than Jamie, how much those words struck home. She made me sit up.

In ‘The Phone Wires’ Jamie muses on how our time on earth is encapsulated in the ‘uncertain water droplets’. As they begin to vanish, they become ‘a winking out here, a tiny extinction there’. There are ghost folk in ‘The Moor’, flowers of this summer only, passing into memory. In ‘The Whaup’s Skull’, she mourns the loss of curlew (the whaup of the title) with a ‘bill like a long nib that could write its own epigraph’, whose ‘sobbing trill’ glides ‘into silence and bone’. Ah! The profound sorrow is thick and heavy and beautiful. How tiny and ephemeral we are!

Throughout the book, Jamie evokes a strong sense of place, something geographers write about, often falling short because it is hard to truly express the emotional, the fundamental. Yet she brings all this together — place, space, time, emotion — it’s her ‘arc of life’. From ‘The Summit’ near her Scottish home, Jamie feels that she is the last one alive, that her task (set by the mountain?) is to go and ‘clear the hill’, clear the cars and turbines, clear everything’, but she then asks what use is ‘that sort of thinking’, rather, if this world ‘is ours to dismantle, it is ours to make.’ So, within the sorrow and worry, there is the hope.

Kathleen Jamie has put into words what many of us think as we grow older, as we question life and nature, and our place in it all. What is our legacy? How will we be remembered? How do we help our children face a world in which so much has changed in so short a time? She says, in a few words that shook me to my core (why, when I know about the science of these things?), that the early 1990’s was the ‘last of the before times’. She picks up and runs with similar sentiments to Andri Snær Magnason (On Time and Water, 2020) who also bound and braided timescales we can understand into the natural environmental timescales of our planet. Jamie, in that one short sentence does the same thing. Nothing in any of the academic tomes and scientific publications have made my heart beat so fast. Yes. And yes again. The ‘last of the before times’. And then she asks, what will the world look like without me, without you, without us?

These small, short pieces of prose and poetry are like lightning, bursts of beautiful brilliance, at times shocking but recognisable, put together and balanced on top of each other. And just as the wind blows through stones heaped on a mountain-top, the delicate art of Miek Zwamborn both threads through and ties together every piece.

We are more than the sum of our parts, Jamie writes. Her new book is so much more than the gathering of words on pages. It is a cairn made from love and loss, sorrow and joy. Her words may occasionally feel quiet but they are profoundly penetrating, with the power to pull our legs from under us.

This book, I think, is Kathleen Jamie’s greatest work so far.

*

‘Cairn’ is out now and available here (£9.49).

Annie Worsley is the author of ‘Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands’, published last year by William Collins, and much loved by all at Caught by the River. Buy a copy here (£16.14). Read an extract here / Kirsteen Bell’s review here.