Kirsteen Bell considers the movements of ravens across the seasons.

After a consistently autumnal summer, the season leaves quietly, gifting the north-west Highlands with a small, still window of warmth. Slinging washing out over a rope, I step past bright purple scabious and heather, and browned ferns gilded by morning light. Thin metallic threadpulls of chaffinch song come from the woods on the other side of the fence, an occasional scrawk from the jays, and little else. The steady punctuation of raven has seemingly vanished.

I always find the change from summer to autumn an unreasonably anxious time. Anxious: because of those quiet skies. The page is cleared oddly blank of ravens and their calligraphy. Unreasonable: because it happens every year. I should know by now they are biding their time, the young dispersing from their parents’ territories, joining flocks, waiting for the seasons to change, to begin anew.

The burbling conversation of two ravens drifts through the air around me, and I look for the birds with relief. It is hard to pinpoint their sound: it bounces off the hills and the house, so at first I think they are nearby, but no — they sail on an unseen thermal high above me, crossing the blue between my roof ridges and the trees. They are relaxed, just a couple of birds chatting on their way to pick up breakfast at the landfill, only giving the occasional wing flex to stay with the buoyant air. No displaying, no playing.

One reason I am so attached to these birds is that they are usually easy for me to observe. As I go about my day — hanging up washing, walking the dog, working at my desk — they tend to be large and loud, tantalisingly present despite their distance. Winter though is when they are most visible, when it feels like the gap between us shrinks.

Fifteen years of living on this croft, and I yearn increasingly for winter. Summer lowers a thick green veil and, as I am neither a naturalist nor have the time to hide myself and observe, I catch only the edges of those lives that exist alongside ours. It is sometimes possible to track persistent calls to a bobbing disturbance in the outer leaves of the nearest oak, and I might see a shining silhouette glide between the trees. Mostly I fill in the raven shape with my memories. In contrast, winter is windswept, exposed, and brings the ravens centre stage. When much of the world withdraws, ravens dance and thrive, finding mates, building nests, and hatching their young on the bare bones of Earth.

A day after the equinox, a north-easterly tears toward us over the loch. I follow it across the field and up through woods that sway and whisper with the wind. Through the back gate and onto the moor, I navigate hummocks and bog until I reach a sheltered dip in the earth. My heading is a small island of lichen-crusted rock, chunks of weather worn quartzite angled in a deep V like a stone hammock. Sitting, I tuck my knees over its sharp ridge. Here I am tilted back, my whole self shifted skywards.

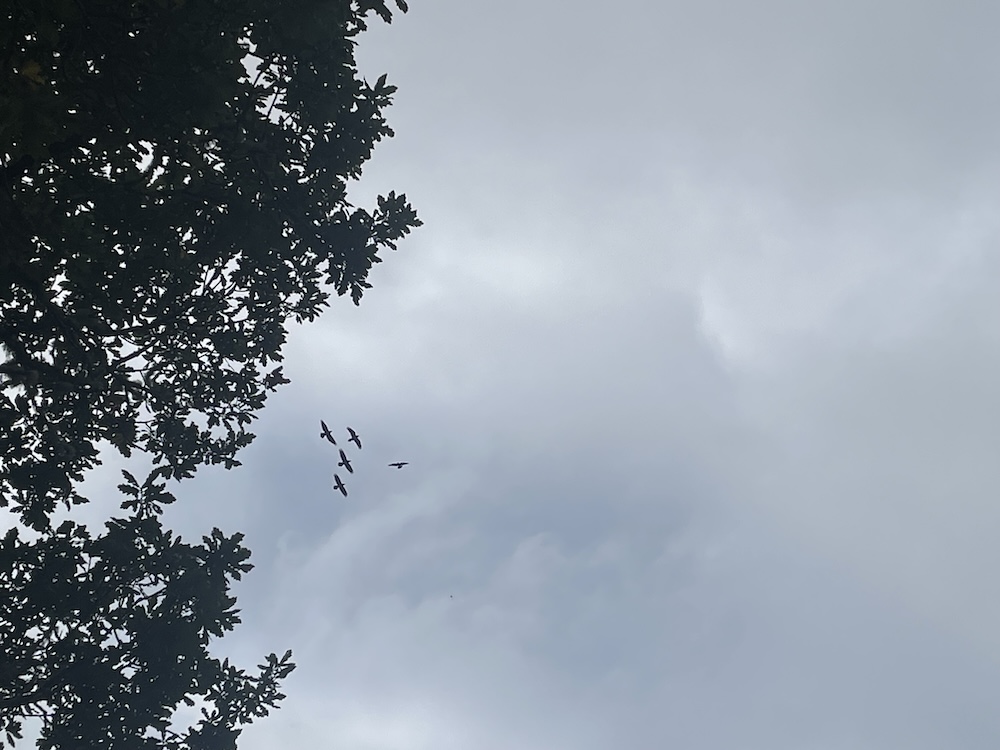

A flock of around thirty ravens surges and swells across the sky; gentle krrks fill the spaces that fluctuate between the birds as they rise and roll, dive, curl and loop, arcing and entwining through the gusts. Three crows have joined the fun, their high-toned caws grating alongside the deeper, guttural calls of their corvid cousins. The ravens swirl briefly into a group like a murmuration, then, as quickly as it has come together, the throng scatters. This is play, delivered with balletic precision and purpose.

Writing in Ravens in Winter, Bernd Heinrich suggests this is the dance of juveniles courting potential mates, often carried out over two to three years before they choose a partner. Those that are paired engage in territorial flights from October onwards, ready for nesting in February and March. But the acrobatics I so love take place almost all year round, and often in large groups of young such as I think these to be. If Heinrich is correct, these are exploratory flights — flirtations, if you like. Ravens mate for life and can live for 20 years, so these exuberant displays of energy are crafted to give each bird knowledge with which they might select a partner who can defend and nurture a family in the cold dark of all those winters.

I watch two separate from the crowd, wings levering with the effort of climbing a tower of air, followed by a fast helter-skelter flight down again.

One rolls below the other, long claws extended upwards then righted, before curving around to repeat the half-pipe performance. Their partner shows no apparent reaction, yet as they slide closer they grip claws for just a moment, like magnets barely touching, before withdrawing and coasting down into the trees, hidden once more.

*

Kirsteen Bell lives and writes on a croft in Lochaber. She can also be found at Moniack Mhor, Scotland’s Creative Writing Centre, where she is Projects Manager and Highland Book Prize Co-ordinator.