Journeyed and lively, Luke Thompson’s latest book reveals the trap of ventriloquism we often fall into when attempting to converse with other animals, writes Abi Andrews.

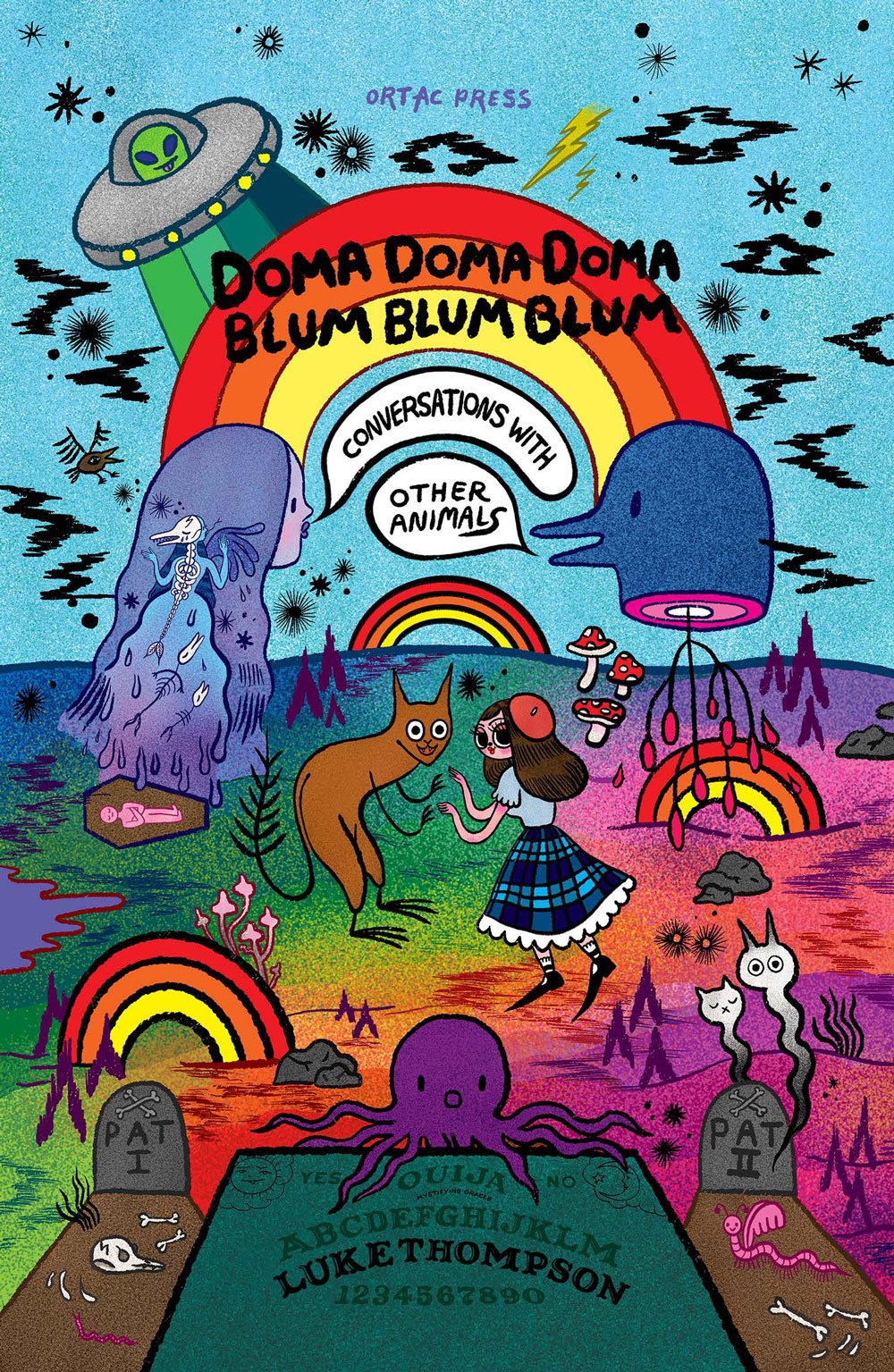

In the beginning, I misread DomaDomaDoma-BlumBlumBlum by Luke Thompson, so I’m letting you know in the hope you won’t then fall into the same trap of expectation as me, and therefore feel more at ease in its playful absurdity. The cover, illustrated by comics artist Donya Todd, is something to behold, and truer really to the spirit of the book, as is the nonsensical title, without its more diverting subtitle: Conversations with Other Animals. Because there really are no conversations with other animals in this book. In fact, there aren’t even many other animals. I may have been stumped by the pinned endorsement on the jacket from the Vice President of the RSPCA, because this isn’t a book much about animal ethics or welfare either. It is not a science book of the An Immense World kind. What it is, is a spirited and humorous tracing of our mostly imagined conversations with other animals, and what these reveal about the root of our desires for them to speak back to us. The ongoing litany is, it turns out, truly wacky.

Dr Doolittle; an investigation into a mongoose poltergeist called Gef; witches’ familiars; ouija boards; King Solomon & ghost dogs. This is not interspecies communication of the Alex the parrot kind. There are spirits and literary figures and fictional characters, and more is revealed of ourselves and our one-sided and very self-centred ‘conversations’. It might have been called Humans Talking for Other Animals, in that it troubles itself with the ventriloquism that we so easily fall into the trap of. Journeyed and lively, Thompson is commendable in his entanglement with his subject, which takes him to the site of a house haunted by Gef the mongoose on the Isle of Man, and into a flotation tank, as well as engaging in experiments with ouija boards and crystal balls.

What often rises up in these investigations, is the dark undercurrent to our desires. Often in our attempt to force communication from other animals, we have caused them nothing but suffering. In most of Thompson’s examples, we haven’t been very good at showing the respect with which we would expect to approach a partner in ‘conversation’, if they were to want to speak to us. The most damning example of this is one of few real animals Thompson approaches: John Lily’s dolphins, experimented on in the 1970s in an attempt to truly engage in interspecies communication. Lily’s approach was seemingly to torture it out of them. He killed up to 8 dolphins over the course of his experiments, which included keeping them captive, shooting them up with LSD and ketamine, and masturbating them. If these are some of our most significant attempts at communicating with other animals, what this reflects back is a glaring lack of empathy or respect. Why should they want to talk to us, then?

Like beat poet Michael McClure shouting his poem at a caged lion in 1966, respect and autonomy has often not been factored into our approaches. If McClure had been inviting a true response from the lion, with no metal bars to uphold a division, the lion’s response may well have been to eat him. To call this artificial human / more-than-human interaction collaborative smacks of the blindsided anthropocentrism that appears to be our default. And nor is this of an era, some arrogance of the avant-garde. Just last month, Cambridge’s Museum of Zoology claimed to give ‘the gift of conversation’ to its taxidermy, enlisting AI to allow visitors to ask questions of the bodies of the deceased animals in their collection. We see ‘conversation’, used as generously here (without any of the probable irony with which Thompson utilises it) as in Conversations with Other Animals. There is a parallel estrangement; like talking to dead animal pets via a medium as Thompson describes, AI acts as a supposed medium, only with the same disguised trap: are either of these really conversations with animals, when humans still sit with their hands up the ventriloquist-puppet’s arse?

Cambridge ponder, ‘Can we change the public perception of a cockroach by giving it a voice?’. Thompson’s book asks a similar question. Do we feel closer to animals when we animate an imaginary mongoose called Gef? We are conflicted beings, as Thompson shows; during the heyday of animal language studies with apes in the 1970s “language”, Thompson quotes Alex the parrot’s Irene Pepperberg, “seemed to be defined as whatever it was apes didn’t have.” We might make absurd attempts to approach animals, but we also go out of our way to redefine the parameters of language in order to exclude them. Scientists who observed responses to complex sentences in animals faced attacks on their methods and even their patriotism, because of the threat towards human uniqueness. Central to Thompson’s book is what this all might tell us about ourselves and our farcical reactions to feeling jealous and lonely on the island of sentience and meaning we have constructed for ourselves.

In their most hopeful slant, Thompson’s accounts tell us about paying closer attention to other animals. If we do, he suggests, we might glimpse a genuine communication, like in the case of the true and understanding bonds we form with our pets. And Thompson insists that there is something important in our attempts and our desire to reach out, suggesting it reveals our yearning to gain access again to a world that has been sealed off from us, a realm of nature we have been disconnected from. ‘Conversing with animals is an expression of this desire for connection, for entangled kinship’, is his generous way of putting it. If you recall some of the ways we have gone about it, this seems a bit of a stretch. Cambridge Museum of Zoology hope their gimmick might go some way towards ‘reversing apathy towards the biodiversity crisis’. If our best hope is human-programmed AI speaking for stuffed animals, then I feel pretty hopeless. Surely we should be able to muster respect, even if other animals never, and with good reason, want to talk to us.

*

‘Domadomadoma-Blumblumblum: Conversations with Other Animals’ is out now and available here (£12.34), published by Ortac Press.