From their respective crofts in Wester Ross and Lochaber, Annie Worsley and Kirsteen Bell embark on a new joint column — bringing their lives and landscapes into conversation.

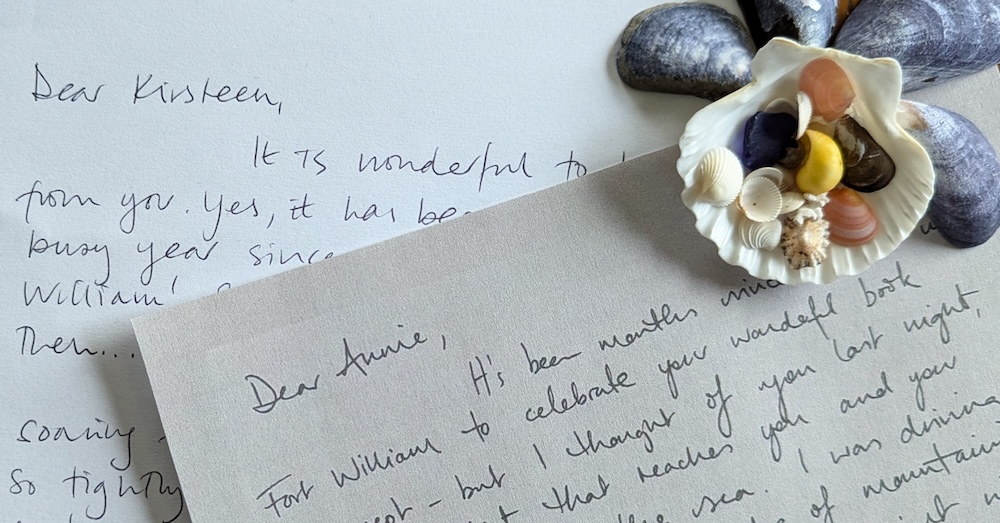

Dear Annie,

It’s been months since we met in Fort William to celebrate your wonderful book Windswept – but I thought of you last night, and the light that reaches you and your croft, so close to the sea. I was driving west inside the amphitheatre of mountains that cradles us, towards a sky alight with hues of violet and gold. The sun glistened on the blackening hill-line for a moment, before it dipped away to finish its light show on the sea twenty miles away. Its flushed light continued pouring up over and between the dark hilltops, gilding the orange bracken on the high slopes above the road, and landing luminous on the loch below.

I was tempted to keep driving, race against the sun and get through those mountains in time to see it dip into the Sound of Sleat. But, it was dinner time and hungry weans don’t feed themselves. So I turned onto the single-track road at the head off the loch as usual, travelling east away from the sun and towards home. Impossibly, I found myself driving towards the same soft light reflected on the Ben. Hill-girt though we are, the light finds us still. I thought then of our two crofts, our wee corners of land and light; mine tucked into the Lochaber hills, yours looking out over the sea from Wester Ross to the tip of Skye and open across to the Hebrides, and both with the same sunset.

Our croft is just a few acres, its east and west boundaries marked out by centuries-old drystone walls on the steep side of a long step of moor. The north boundary is the rock-strewn shoreline, then you must climb up through rushes and bramble, past birch, rowan and hazel, to meet our south boundary, 190 feet above sea level.

I think I remember your croft is in a flat strath? Here, everything grows skyward against the gradient: hens, pig pen, woodland, even the polytunnel tilts to stay upright. Everywhere there are ditches like veins, overgrown with forget-me-nots in the spring and clogged with tiny gold birch leaves now as we approach winter. Despite these attempts at channelling the rain, the peaty ground is perpetually wet, and every surface of stone, bark and soil is soft with moss.

A digger had to clear level ground into the hill when we built our house. Its wide windows, pebble dash walls and grey slate roof are flanked by the roofless ruins of previous crofthouses. These tiny, thick rectangles of stone were built strategically on little knolls or at the tip of a bank to keep their dirt floors dry, and so as not to encroach more than they needed to on arable earth. My father-in-law told me that this whole croft was cut for hay once and had to be scythed by hand as parts were too steep for a tractor — hard to imagine as it is such a hodgepodge of habitat now.

We still call the largest of the ruins ‘Mary McIntyre’s’, regardless of the fact that Mary moved away in 1915. Her family had been here since the croft’s creation during the first, less brutal, wave of the Highland Clearances. She signed the croft over to a neighbour, who passed it to my husband’s grandfather, and it meandered its way down through time to us. Mary’s doors and windows are now gone, just the shape of them shown in the worn, lichened stone, and her thatch roof has been replaced by the long arms of an old oak that wasn’t even an acorn when she left.

You will have stone ruins on the croft too, won’t you? Or maybe yours are still an active part of the croft’s life. I say ‘yours’ — what an idea, that we could ‘own’ the remnants of so many lives. You and I are just another layer in the palimpsest of these little pockets of land and time.

It won’t be long before the zenith of the winter sun sits below the south hills and we will only be able to catch the light askance through the short winter days. I might travel north to you then and breathe in what I imagine to be your sea-swept skies. But if you ever take a notion to coorie inland, you know where to come.

With love,

Kirsteen x

*

Dear Kirsteen,

It is wonderful to hear from you. Yes, it has been a full and busy year since we met in Fort William! So much has happened since then.

Your letter sent my mind soaring to the mountain tops. I’m not so tightly wrapped in the embrace of high summits but the Torridon ‘hills’ are the backcloth to life here. I see them every day, standing tall and proud at the head of our valley, often glowering but at other times bursting with light and colour. When winds pour in from the west, they carry all kinds of weather (and thoughts) inland. I am now wondering what direction they would take to fly straight to you? (I must seek out a map!) As the golden eagle flies, the distance to your croft won’t be huge will it, but oh my, what a journey by road. Yes, one day I will come!

As I write, the afternoon light is spilling down the mountain slopes, all copper and bronze. The air is sharp — there has been a sudden drop in temperature — so the finer details of shape and form, the landscape’s intimate terrain, is revealed. I think I can smell snow in the air but that may just be a fancy!

I know Loch Eil and the amphitheatre of mountains you describe. I love the notion of being cradled by them, light seeking you out wherever you are. We are so lucky to live in clean, clear air, aren’t we! Here in the Highlands, light and colour are so true and honest. And as the days are shortening quickly now, we need such spells of sunlight more than ever. By the time midwinter comes, we’ll be grasping tightly to the daylight hours. No wonder you were tempted to chase the light to the Sound of Sleat!

Yes, our skies, our croft, our lives here are sea– and wind– swept. There are very few days without wind of some sort or another, but it enhances the light somehow, both gentling it and making it fiercer.

Red River Croft is open to the elements. There is very little in the way of shelter here apart from a ring of hedges and a small woodland. Together they protect our house from the worst storm winds of autumn and winter. Home is in an old river valley about 100 metres from the shore and roughly 30 metres above sea level. And yes, the lower valley was once a strath at the edge of a small estuary. Over millennia the River Erradale (Abhain Dearg) cut its way to the sea creating a series of river terraces, and on one of these sits our wee house. The croft, about ten acres in all, straddles the river, from one high embankment to another.

So, our ground is flat compared to yours. It made me smile, to think of everything on your croft striving to stay upright. Most crofts here in this part of Wester Ross are fairly flat with small de-crofted plots for houses, and all but one or two in my crofting township are plain square fields of grass. Ours is different; perhaps because of the river, but also because of us and how we have managed it. The topography is interesting and uneven, but nowhere near not as sloping as yours. There is a mosaic of environments — wet and dry meadow, peat banks, riparian and scrub habitats, and naturally rewilding patches along ditches and embankments.

There are ruins here too. One rectangular structure still contains a fireplace and must have been a beautiful house once. The internal space is full of aspen and when the wind blows the leaves whisper. If I close my eyes and listen, it’s hard not to imagine they’re the voices of people who once lived here. There are much older piles of stone, some cleared by crofters in their efforts to improve the ground, and others even more mysterious. Two circles of stone may have been roundhouses predating any of the crofts. The tales these boulders and field boundaries could tell! Memory stones, covered in moss and lichens.

Is your croft part of an estate? I would love to know more of its story, of your story. The relationship between land and people fascinates me almost as much as the history of these great mountain landscapes, their geology and geomorphology and so on. Here, the social history is as tangled and troubled as anywhere else in the Highlands but you wouldn’t think it this afternoon. The late burst of golden sunshine is a soothing balm.

The days are shrinking fast, aren’t they? On dull grey days I love to head out to the shore to let the winds blow my thoughts and cobwebs away. Do you have a special place away from the hubbub of home and work to fly to?

Loch Eil is a sea loch, yes? I imagine it to be a gentle place where the water is patient and calm and full of bounty. Ach! So many questions! Please say more when you have time and your bairns allow.

With love,

Annie x

*

Kirsteen Bell is a Scottish writer of narrative non-fiction and sometimes poetry. All her words are gathered from the croft in Lochaber where she lives, and the surrounding Scottish Highlands. Her writing and reviews can be found in such places as Paperboats, Caught by the River, The Guardian Country Diary, The Lochaber Times, and Northern Scotland Journal. Kirsteen can also be found at Moniack Mhor, Scotland’s Creative Writing Centre, where she is Projects Manager and Highland Book Prize Co-ordinator.

Annie Worsley is a writer, crofter, grandmother and geographer with an enduring love of the Scottish Highlands. In 2013 she and her husband moved to the crofting township of South Erradale near Gairloch. While her husband was a community pharmacist, Annie worked on Red River Croft. She began a blog about life on the croft and then wrote essays on nature and environment for various publications including Elementum Journal, Women on Nature, the Seasons’ Anthologies edited by Melissa Harrison, Caught by the River and Inkcap Journal. Her first book about life on Red River Croft and the natural history of Wester Ross, ‘Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands’, was published by William Collins in 2023, and is out now in paperback.