Neil ‘Tomo’ Thomson shares a year of nighttime navigation and cosmic dread.

Painting by Freya Tate

Painting by Freya Tate

‘Te Po-te-kitea / The night in which nothing is seen / Te Po-tangotango / The intensely dark night / Te Po-whawha / The night of feeling / Te Po-namunamu-ki-taiao / The night of seeking passage to the world / Te Po-tahuri-atu / The night of restless turning Te Po-tahuri-mai-ki-taiao / The night of turning towards the revealed.’ — Christina Thompson, Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia

Another year of roads, mostly at night. These journeys (the longer the better as far as I’m concerned) always being the most mediative — at times even transcendental. The night always seems to hold more possibility than the day, thanks to the quietness certainly, but also the air clears at least a little from the furious traffic of the waking hours; there are fewer machines emitting electronic noise as their operators lie beneath jaundiced streetlights in their suburban comas.

The mind sees so much further in the dark than the light. I found an eccentric switch (on the dashboard of my car) that dims all the instruments, leaving the cabin in almost-darkness except for essential info, the idea being to amplify night vision. Racing through the darkness across Europe I could almost imagine the world outside crumbling completely away, becoming surrounded by void, geology itself even vanishing beneath the wheels, only the seemingly eternal deep time of the galaxies above to guide the speeding car. However, it’s not hard for me to imagine these wet motorways and autobahns being the modern mirror of the sea lanes of the past. I’ve read about Magellan, Cook, and Vasco de Game but Christina Thompson’s Sea People struck me, describing a pre-and-post European contact.

It’s the earlier Polynesian navigators who somehow crossed the vast Pacific Basin settling on pinpricks of land, voyaging for thousands of years before Europeans arrived with compass and sextant, that Thompson investigates in Sea People. Anthropology and modern science are still mostly at a loss to understand how these people populated such tiny specs of land amid the abyss of water of the Pacific Ocean. The 2600 miles of nothing between Otaheite (Tahiti) and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) for example, were home to thriving pre-contact populations. These navigators, or wayfarers, had no written language, no texts, just oral tradition. They could memorise thousands of impressions of the stars in the night sky in relation to their positions: they were people who understood the night with a profundity we can’t even begin to imagine. They saw information in currents and waves, could read the tides and ocean swells in what to us, from an aeroplane window perhaps, is just an eternal blue void. It’s overwhelming to imagine a world so pristine and elemental in this Anthropocenic age, riddled as we are with environmental guilt and angst. Researchers at the University of Hawaii have established that these navigators used sticks, twigs and stones to make a version of sea charts. We might picture them sharing the knowledge gathered with found materials on white Pacific sands.

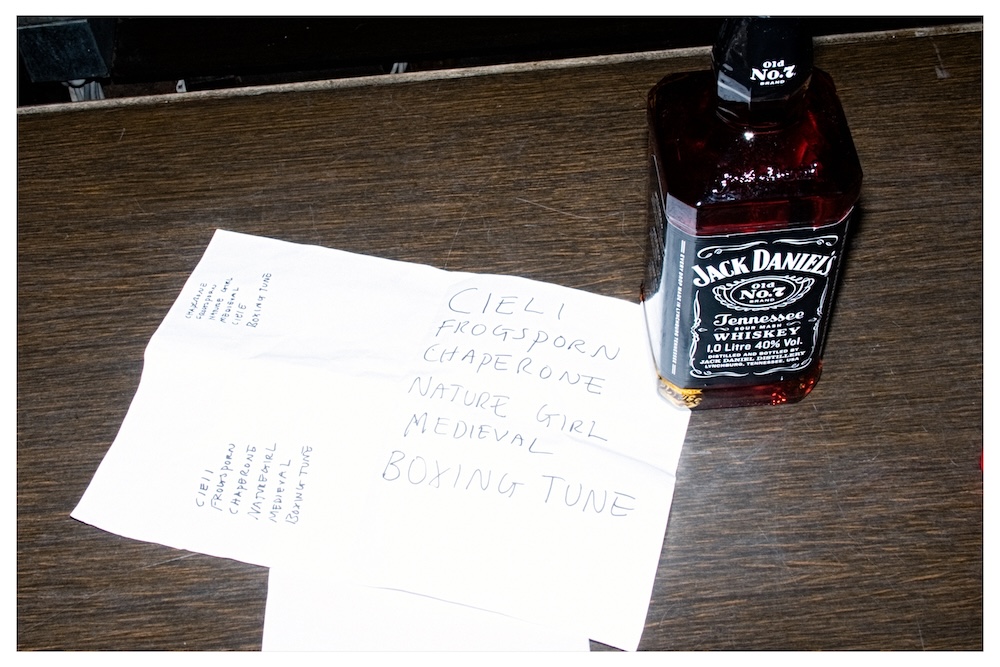

I thought of these charts one evening by a lake in Nijmegen. I’ve spent much of the year in elliptical orbit through the storms and the lights with a band called Mermaid Chunky, two brilliant artists and musicians (magicians?). We’ve shared thousands of miles together, from Total Refreshment Center in Dalston to the streets of Antwerp via the countless dark windowless rooms and bright festival stages in between. That evening Freya from the band and I sat on the lakeshore, attempting to make a map of that unfamiliar festival site from pebbles and twigs as LCD Soundsystem wailed from a huge stage across the water. Perhaps we were trying to make sense of our unfamiliar surroundings, charting our position, making patterns in the sand to anchor us somehow to these Lowlands neither of us had ever visited before and probably never will again. An act of recording time and place maybe, like the hundreds of photographs I have taken of them this year.

The cosmos visited again one summer afternoon on Margate beach. My friend Philly Kev died last year, and to mark the first anniversary of his passing, his friends and family held a fire ceremony on the beach below Cliftonville. Kev and I would sometimes sit by the windows on cold winter’s evenings at Bar Nothing (me wheels down after a long tour) and look out and watch the creeping coastlines of light (a title of my favourite Mark Lanegan song, also no longer with us). Kev would keep a pair of binoculars by the window and we would observe the ships at anchor. We’d check their names, cargo, destinations and departure points on the Maritime Traffic Apps on our phones, often with the porous desert rock of Kyuss’s ‘Spaceship Landing’ on in the background. That song was a favourite of both of ours.

At the beach memorial, Tree Carr presided over a ceremony shot through with magic and meaning. Surrounded by Kev’s friends and family, Tree summoned elements from all corners, water, wind, sun, reminding those present on the beach that fire is the original element — that the same fire we were gathered around is the fire of the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, that brought everything and everybody we know, have ever known and ever will know, into existence in a single detonation; a singular point of heat and light. She described it as “the first act of magic”. As I sat on the beach listening I let handfuls of sand run through my fingers, imagining each grain to be a star (which they sort of are) and, albeit briefly, felt a connection to the universe which I normally find cold, empty and unforgiving. That afternoon those in attendance shared cosmology and loss. It was very, very powerful.

Many Polynesian creation stories, as described by Christina Thompson, mirror that very first cosmic event. According to these mythologies, the universe began in something known as Te Pō, a period of chaos and darkness, the void where we still exist in the states before birth and after death. Te Ao is post-Big Bang perhaps, the period of light and warmth.

‘We live in Te Ao, but it is from Te Pō that we come, and to it that we ultimately return.’

Virginia Woolf once wrote in her diary ‘to walk in London is the greatest rest’ and, when in town, I walk miles every day with my dogs — our own two Staffordshire Bull Terriers, or my clients’ dogs. It’s not something I could do in the so-called countryside. The grinding boredom of the rural landscape of agricultural monoculture is pure sensory deprivation compared to the slow dance of the city. I love the drift and whine of the sirens and the constant low hum of traffic. “You’re never alone with a drone”, as Andrew Weatherall once said.

There is a tree on Hackney Marshes I pass several times a day. It’s always a small epiphany when I notice the first few leaves turning in early September, meaning cooler weather is finally on the way. On the other side of the turning year, the death of winter is signified by the tiny specks of colour of crocus, like light catching discarded glitter on the dancefloor. Headphones are a constant. My friend Annabelle Mödlinger (of The Umlauts) has a monthly show on NTS called Roadkill Ikebana which is always a highlight when out with the pack those Tuesday lunchtimes. Curation is almost an act of resistance now, the perfect antidote to the suffocating hegemony of our algorithm overlords.

Each year there continues to be astonishing music. I formed up with Atlanta’s Revival Season for a while. They are injecting new light into Hip-Hop, documented by the brilliant photos of Julia Khoroshilov. One day, just for the hell of it, we all drove down to Margate with Bones the puppy, windows down and wind howling, running through B’s very extensive Rap Rolodex. I recall we laughed all the way there and all the way back. We’ve adopted another dog — he chose us, we didn’t choose him, as it should be. He was in need of a new name. Revival Season suggested ‘Haint’ (an Appalachian term for ghost). He is snoozing at my feet as I write.

Bones, Tomo and Jonah in Margate, photographed by Julia Khoroshilov

My partner Rhian’s late mother was a very accomplished classical musician and teacher. One of the many sadnesses of her early passing was that her beautiful viola has languished since. We were delighted then to find it a new home in the super talented hands of Magdalena McLean, and she’s been playing it all year, including one magical night in Highbury when she joined The Breeders on stage for ‘Drivin’ On 9’ amongst other tracks, and we watched, blown away as that most charmed of wooden objects came alive again.

Moin, Butch Kassidy, Mandy, Indiana, Boy Harsher, Eye Hate God, the Iranian Punk of Shieva, among many others have soundtracked the year, but it’s left to Godspeed You! Black Emperor (of course, it had to be them) to articulate the many current horrors of our time. New album NO TITLE AS OF 13 FEBRUARY 2024 28,340 DEAD is an astonishing record to accompany the not very distant rumble of Near Eastern airstrikes, with track titles like ‘BABYS IN A THUNDERCLOUD’ and ‘RAINDROPS CAST IN LEAD’. I revisited Season One of True Detective, which articulates the cosmic dread of these times better than anything else still. I read someone describing it brilliantly as ‘Drunk cops battling Elder Gods’, which sums it up perfectly.

In 2003 humans created five billion gigabytes of digital information; by 2013 it took only ten minutes to produce the same amount of data. It can’t bring myself to look at the current figures. One bright beautiful Friday lunchtime in mid-Wales in August, I found myself on the main stage at the Green Man festival. Mermaid Chunky had been offered a last minute slot, and as I looked out into the crowd from behind the band, I tried to estimate how many people were watching but soon gave up. I did notice, however, most of the sea of people had phones in their hands, data streaming the performance at light speed across the Black Mountains, cascades of video racing upstream to the GEO satellites stationed 786 kilometres above the equator and then on to potentially envelop the world. These devices are a source of irritation to artists and audiences alike, but this collective sharing of performance seems astonishingly powerful to me.

Mermaid Chunky exist in the long tradition (albeit with the electronics of Roland drum machines and a Notation X Station) of the carnivalesque, from Twelfth Night to Todd Phillips’ Joker, where anarchy manifests, roles can reverse, authority is ridiculed and people gather. As Barbara Ehrenreich states in her book Dancing in The Streets: A History of Collective Joy,’The urge to transform one’s appearance, to dance outdoors, to mock the powerful and embrace perfect strangers is not easy to suppress.’ But don’t mistake carnivalesque for twee, for Mermaid Chunky’s performances are part of the tradition of resistance. There is also a sense of the uncanny — the Unheimlich is shot through in their art, with colour, noise and a little bit of potential violence. Surrounded on the stage by the flashes of colour and animalistic costumes of the dancers from Boss Morris and Vomiton Collective (both frequent Mermaid Chunky collaborators) I felt those ancient Polynesians would have found much of this Deep Time Universal Rave very familiar.

The crowd individually broadcasting these shows took me back to Larkin and his poem ‘Broadcast’. Long before the smartphone era, the poet found himself listening to a BBC Symphony Orchestra broadcast live on the radio, streaming to his flat in Hull. His partner at the time, Maeve Brennan, was at the concert and somehow they shared the experience, displaced geographically, yet sharing some form of collective joy. Empathy, loss, loneliness and longing in the maelstrom of noise. ‘The glowing wavebands, rabid storms of chording…Leaving me desperate to pick out / Your hands, tiny in all that air…’

The road is bright, the road is dark, the road is long…