Richard Foster recounts a year of etching, editing, and dances with danger.

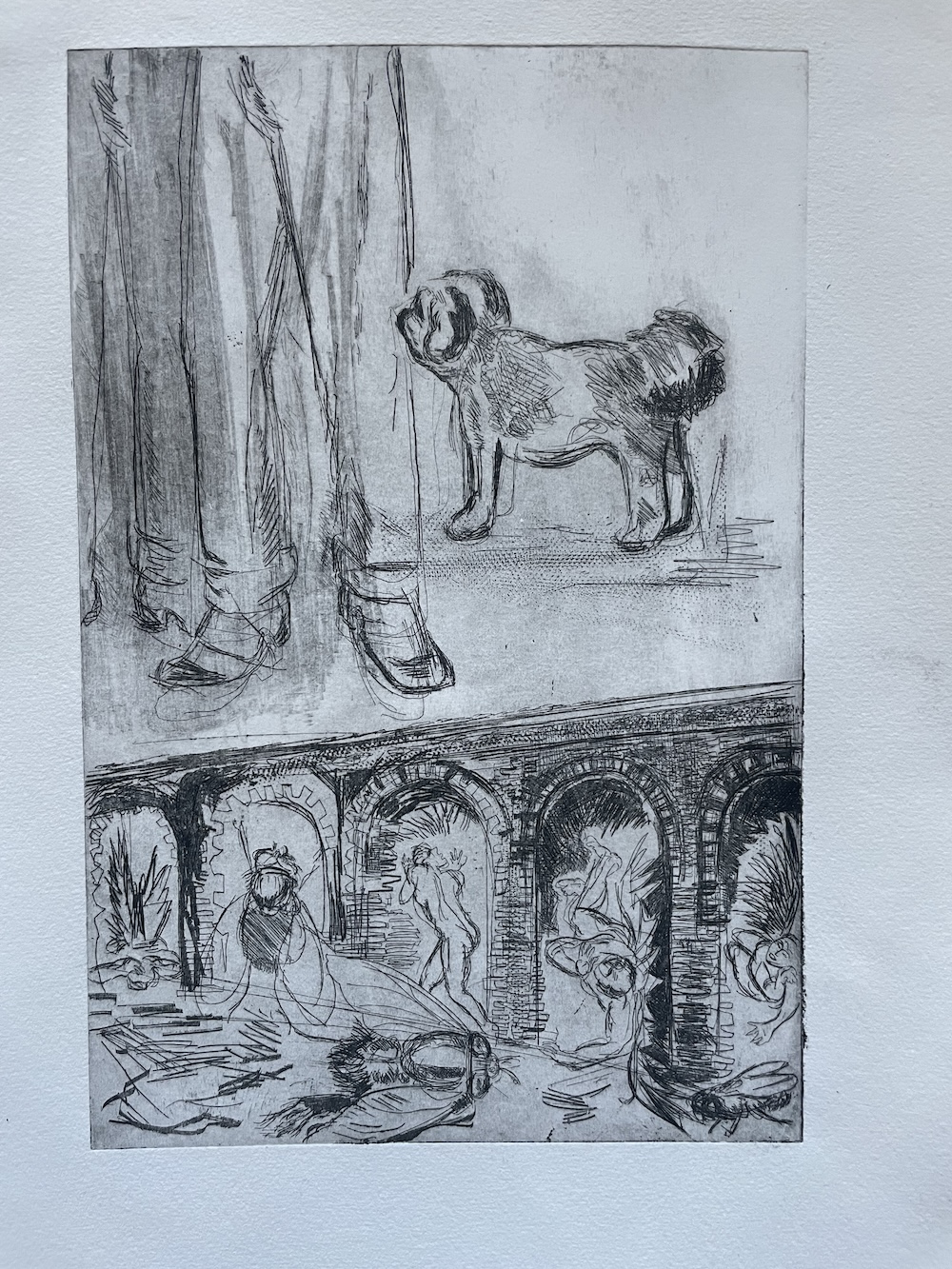

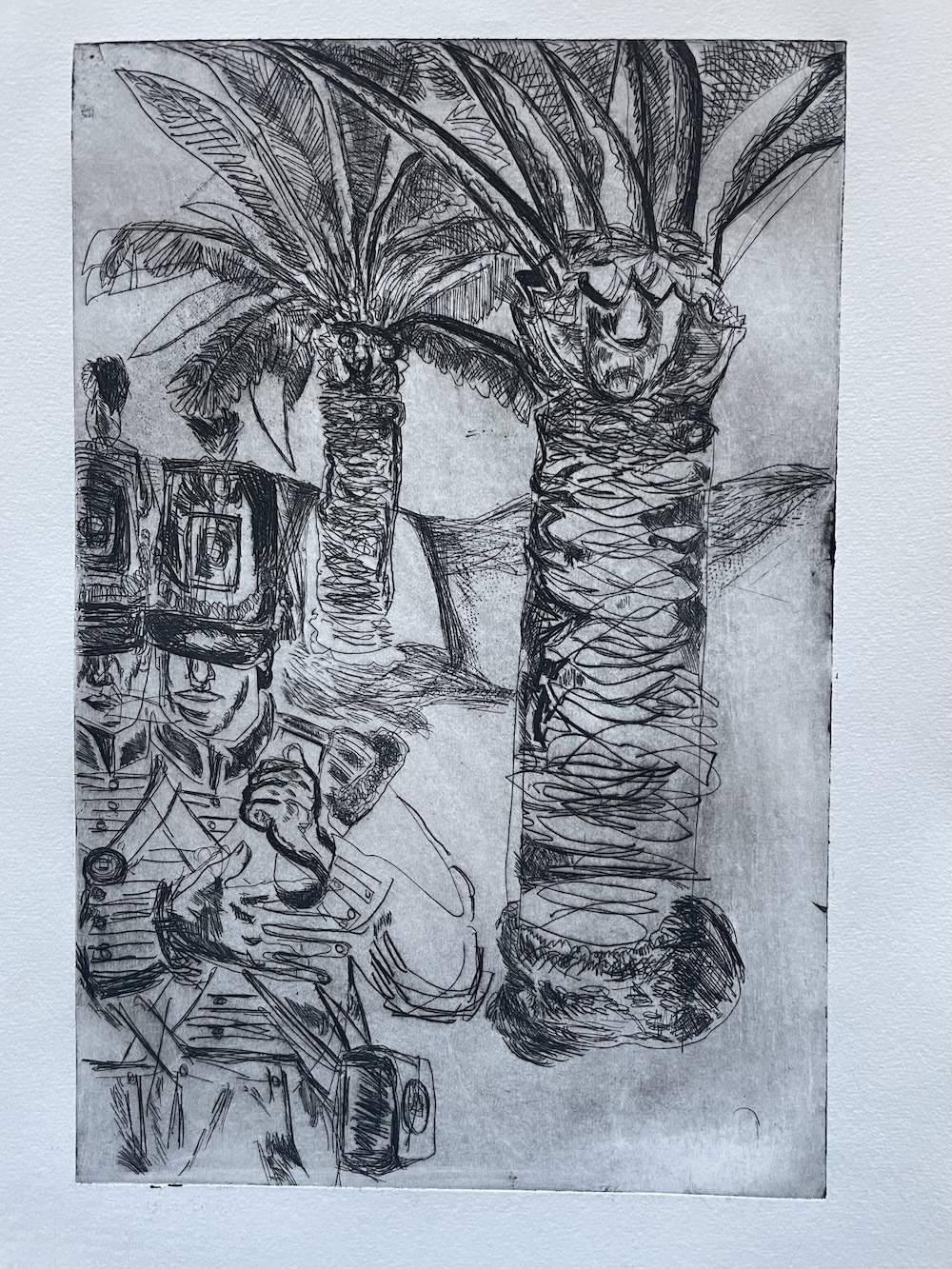

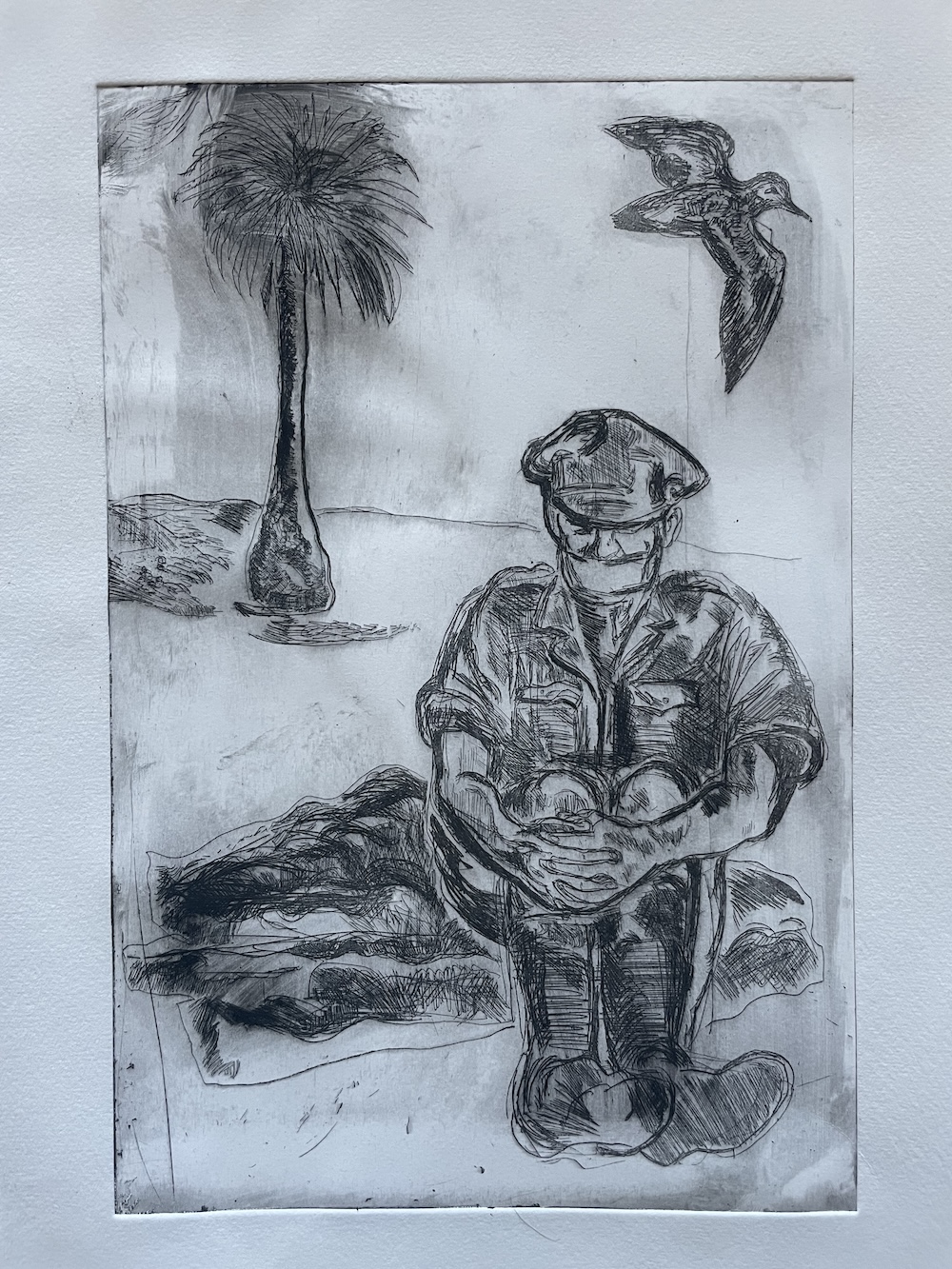

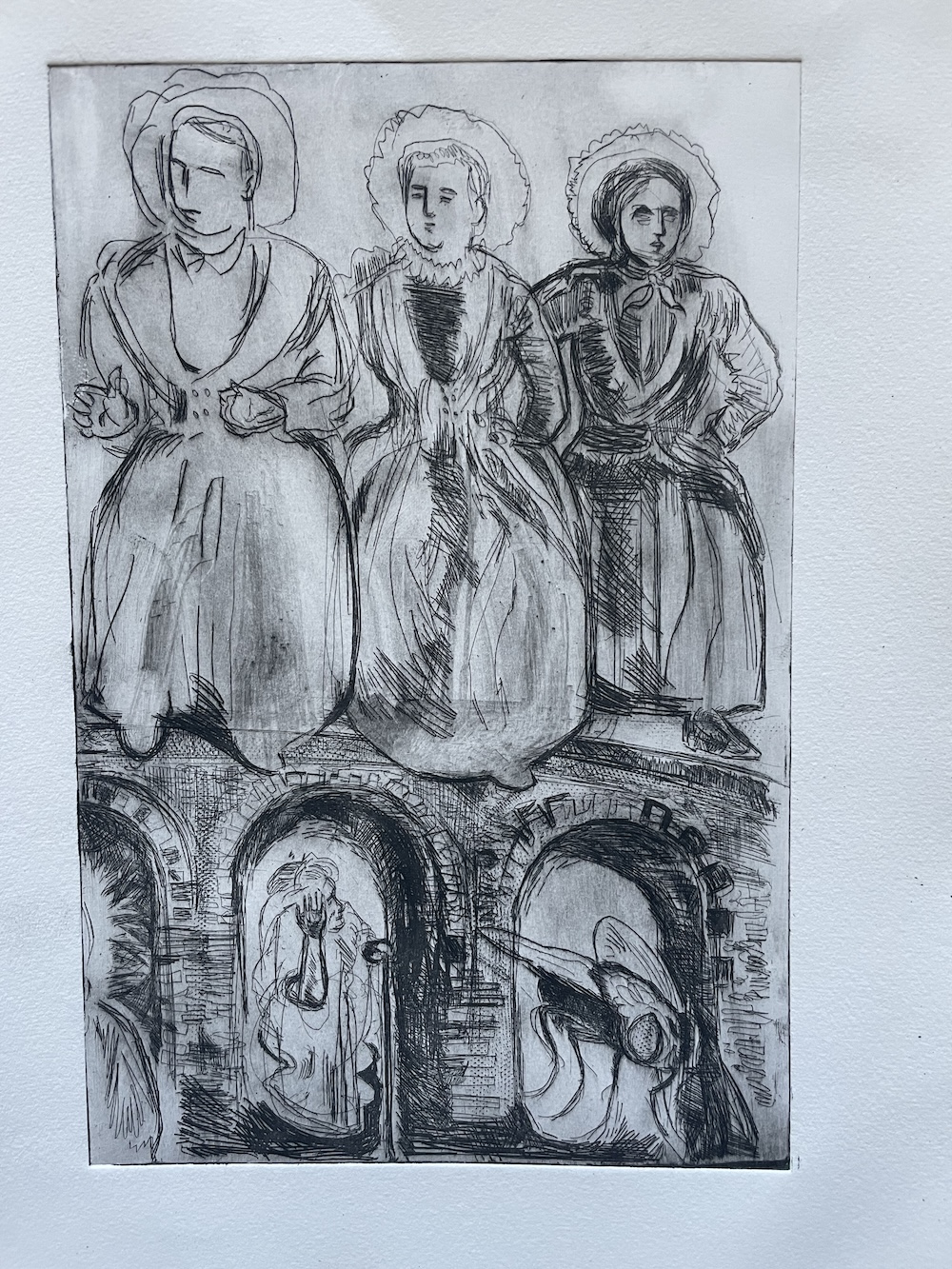

All etchings from Richard’s series ‘The Afternoon Men’

I just can’t seem to remember much…

Yet, how? Why? This last year has, at some level, called upon my memory like few others. The process of editing a book I had written in late 2023, with all the microcosmic adjustments and reappraisals that process demanded, felt like carving a rood screen with a penknife.

Soon after finishing the book, and trying to shake out all the extra words I had in me into something useful, I joined the then untried, soon dreaded, now hated, S*bst*ck, to write a family memoir of sorts called PINS: a game of memory using the rules of a wargame my late autodidact father had started to make but never finished. The plan was to marshall everything I could remember my departed family and friends ever having said, and use those phrases to make, or shape, new rules. (It was meant to be a catharsis of sorts, after a depressing parade of years full of quarrels, funerals, probates and house sales, and the initial idea did sound good in the pub, I will grant you.) PINS became a grandiloquent exercise in — to quote Billy Mackenzie — message oblique speech. Fun, but also knackering. Not least because I made an accompanying post of illustrated photocopies and memorabilia on my website, The Museum of Photocopies. (Something else I happen to do for no apparent reason…)

Writing begat reading: somehow I have read — and I’ve just checked — fifty-five damn’d, thick, square books so far this year, including one that details (with the sober brevity given to those who have facts at their fingertips), the development of French agriculture under the Vichy administration. After all that, there was the usual business of reviews, articles and opinion pieces for a number of publications; some on CBTR, too. Over one hundred thousand words written, numberless read. My brain, with whatever cortexes, campuses, lobes, pathways and depositories it comprises, should be able to pick up a telephone directory unaided.

My hands got a workout, too. I started etching classes in Leiden with a huddle of septuagenarian enthusiasts, all experienced hands in the game. At first it was a wildly intimidating experience. It wasn’t just the learning of a complicated and sometimes demanding creative process that went against all my impatient impulses to just “make something”. Seeing my classmates’ subject matter — uniformly nice and beautifully executed seascapes, wildlife portraits and wonderfully intricate floral decorations — had my heart in my boots. Here’s me, thinking I could draw. And this bunch of quiet, dedicated Dutch pensioners were doing it for fun. One gorgeous headshot of a grebe nearly had me in tears of embittered envy. Still, the tangy fume of the etching ground, seeing — and quietly rejoicing in — the claggy remnants of ink under my nails, and the excitement of seeing a damp piece of paper suck up the ink from a new plate under the press, is addictive now. And, better, my class inducted me into their secret after-hours snifter in the studio canteen — at reduced prices. Emboldened, I have joined the linocut and woodcut classes. This is proving more difficult: for one thing it takes ages to cut things out. And — maybe it’s my battered, Eeyorish old soul — I like my marks to be dark. We will see…

So there we have it, quite a bit, actually, if you leave normal life and work out, and I am in theory all ready for bringing my new book into the world.

And yet everything, still, seems a blur.

“I can’t see like I used to.” My wife fiddles with her reading glasses. Suddenly short-sighted, she’s unsure what to make of wearing glasses, constantly adjusting them on the bridge of her nose, or trying to stop them falling from where they are perched on the top of her head: that kind of thing. I quite like them. They make her look cuter.

Talking to her, I am drawn back to our wedding anniversary in January, a miserable Monday, sleet falling, cold. The radio on, bucking us both up for the day ahead.

And the call, barely ten minutes later.

“Can you come and get my bike? I’ve been hit by a truck. By the lights.”

Then silence.

After that, a neon-infused blur of ambulance lights, medics and policemen, concerned passersby and the sight of my wife’s bike, with its thin wheels playing footsie with the huge tyres of a stationary lorry.

One thing does stick out from this year, then, yes, there is one thing I can remember, now that I remember to remember: the sight of the hospital clock, and the attendant thought of me, there, realising I have been staring at the clock for an hour, wondering what kind of person would return as my wife. Ahead, and yet unbeknownst to me, a few days’ worth of amazed, barely ingestible relief and lark-like happiness at the near-total escape she had, then months of mental and emotional and sometimes comical physical rehab, anger at a police force that said they couldn’t do anything, anger at a driver from somewhere else who had driven through orange turning to red, probably because he was going to miss his connection and his load-in, and therefore his job. Anger at the way a facade of decency, and social care, and “I pay my taxes me” expectance of societal responsibility, and at the meaningless words thrown around corporate spaces without a by-your-leave mean nothing in real life. Just another story from the vast, increasingly-soulless and tarmaced transit park that is Western Europe where people, increasingly isolated and sedate, just want their products on time. Roll on 2025.