As she looks back on the year her Nature Library found a permanent home, Christina Riley celebrates libraries as places of limitless potential.

It’s often said, and rightly so, that libraries are more than just books. It’s usually said when highlighting additional services the modern library offers communities, such as ‘unofficial creches, homeless shelters, language schools and asylum support providers’1, but even when all a library does offer is books, it offers more than books. From the moment the first person walks in, the first conversation or the first turning of the page, it becomes limitless.

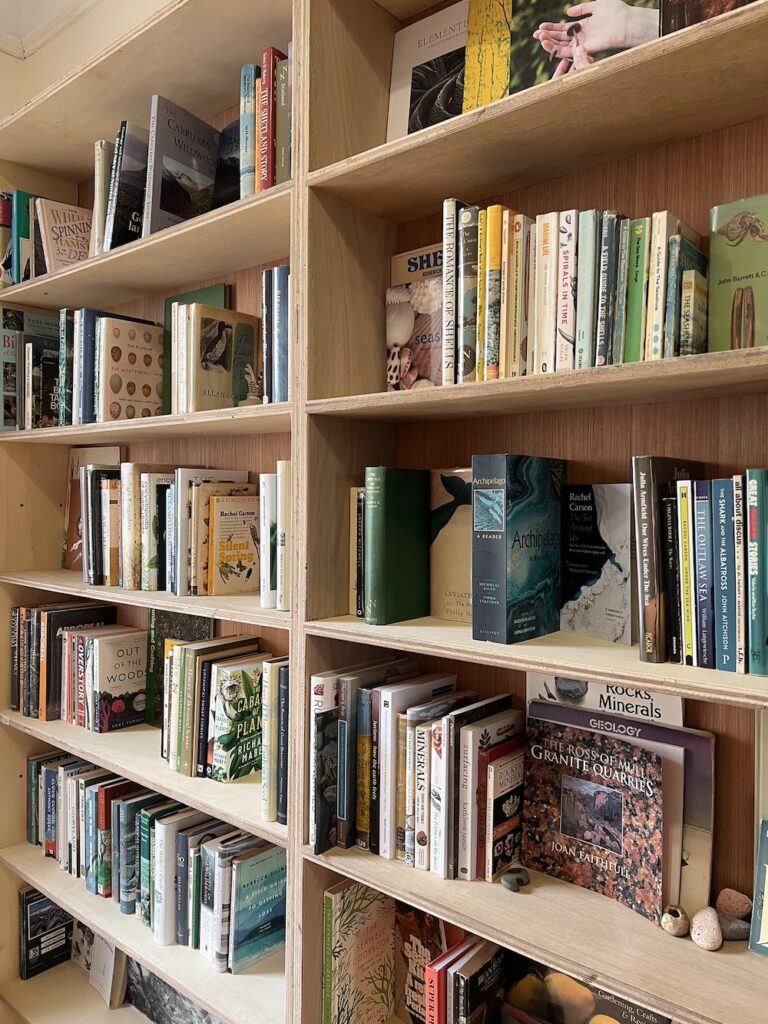

When I started The Nature Library it was because I had a collection of books about nature I wanted to share. By putting them in one place they formed, by nature, a library. A library by definition. A single word (I just wrote ‘a single world’ by accident). For the past five years it’s been popping up across Scotland, from Moniaive to Ullapool to Ayr to Dunbar, for a few days or weeks at a time and my goal — a loose one with no route or time frame given that I’m a librarian by happenstance as opposed to by temperament or training — has always been to one day find a permanent space for it. For the library to become a “proper library”. (By that I mean, you can take a book home and if you come back to return it a few weeks later, the library will still be there.)

Following a series of fortunate events and serendipitous meetings, in spring the library took up residence in one of the Scottish Maritime Museum’s old shipyard worker’s flats at Irvine harbourside, just up from my gran’s old house and just down from where I’d buy two Gregg’s sausage rolls for 80p on my lunch break at my first job. The public library of my childhood, since moved, sat somewhere between the two. For the past seven months The Nature Library has been, forgive me, rooting itself as a “proper library” in this small square of Ayrshire.

It’s unsurprising, then, that I’ve been thinking a lot more about libraries this year. My understanding of them, the forms they take and the communities they shape, their malleability and their magic and their value. What is surprising is that I’ve thought about the books less. Sort of. In a way. Of course, the books are there. They hold the library together. They’re beautiful and enriching and they smell good and one of them might change your life. But when I look back on this year I don’t necessarily see the books, I see people. It stuns me to think that they were unknown to me before May. Artists, activists, gardeners, horticulturists, filmmakers, poets, vets, chefs, students, politicians, arts workers, conservation workers, volunteers, geologists, bookbinders. Readers. Bringing knowledge, humour, kindness and company every time they buzz that door. I find myself thinking that this isn’t a fair exchange and recall a statistic: ‘for every £1 invested in a library, the community gains £7 in social capital’2. There’s one visitor who, every time we say goodbye, leaves me frantically typing in my Notes app the things he’s said or told me to look up. These include but are not limited to (unedited): joseph boyce dance cage, west kilbride glen, mkilwinning abbey records disappeared, im in a forest the shape of a ship, anthony gormley, edgar allan poe was in irvine, irv new town artists, behind dundonald castle, female photographer hitlers bath, send link to sue mushroom sounds.

One day, a family of five comes in. They disperse between the two rooms and the youngest, barely beyond toddling, butter-blonde curls and eyes like blue moons, runs back and forth like she’s trying to win a prize for it. She picks something off the shelf and shoots full pelt back across the hall, grasping the book with both hands. Back and forth and back and forth, showing what she’s found to as many people as she can and as fast as those tiny stomping legs can take her. Passing my desk she stops in her tracks and smiles with that glint acquired around age two, beginning to understand the concept of limits and, specifically, that they can be pushed. I smile back — a green light — and off she runs again. Eventually the girl and her book settle on the lap of mum, who points to the pages and reads the story softly into her ear in German. They took home a children’s book which had been donated earlier that morning.

There have been 57 books borrowed and more donated than I can count. The generosity is staggering, and the gratitude often goes both ways (too many books and too little space, usually). Since May, on top of books, the library has been gifted: ten small bird nests, one large bird nest, a rowan tree seedling, a jar of rosehip jam, a bottle of wine; a bag of perennial seeds, one photo of a butterfly, a poster of a privet hawk-moth, a poster for listening with, a CD, an ammonite fossil, a handmade sketchbook, a tiny bouquet of wildflowers, a welcome wreath, two wooden chairs (reupholstered in hand-weaved fabric by the donator), a plant; focaccia and a great number of canapés; one floor cushion made of old ties, one unidentified fossil, a tea towel, a fragment of a wasp’s nest. And time. Precious time!

It’s a small space but opening the door at 122B Montgomery Street this year has pried the world open a little more, letting the good come out. It’s like when, as a kid, I’d watch my step-brother play Civilisation where the world revealed itself as you walked out to its edges, filling in the blank spaces. (I also feel this way when I walk down a street I’ve never walked down before, especially if it’s in a town or city I’m otherwise very familiar with.)

A library is more than the books it holds. Of course. A restaurant is more than the food it serves. If eateries were taken away I don’t think the public would cry out “Where, now, will we eat?” but rather “Where, now, will we go?” Where will we gather? This year I’ve been more concerned than ever by the eating away of support for arts and leisure spaces and the normality, the perceived inevitability, of an increasingly individualist society. Cuts and closures to libraries is just one example of communities having places to gather (for free!) taken away from them. In the library, a friend told me with some despondence about a company — I believe it was a bank — advertising how many of their features were now “contactless”. Contactless. I hadn’t thought too much about the word before, and now I can’t get it out of my head. What does a trajectory towards a contactless society mean for a social species? Who has asked for it? Who does it serve? One of my last books of 2024 was Heather Parry’s Electric Dreams in which she writes: ‘the underlying economic system for four decades now has been one that encourages a turn away from communality generally…For all my life, the underlying economic policy has been this; profit for the capitalists must reign supreme, and the idea of human cohesion is a threat to the margins.’

Access to communal spaces, self-led education and leisure, a warm space we don’t have to give someone money to be in, should be a given. It’s not actually a huge ask when you consider what else the government funds. In the last 15 years, one in five public libraries in Scotland have closed. In the middle of a cost of living crisis, a climate crisis and with rising misinformation, I and many other librarians (proper ones) would argue that there should be stronger legislation protecting public libraries from closure. Talking about “the power of words” in the middle of a crisis, climate or humanitarian, feels futile. But irrefutable. Access to trusted information is becoming more important by the day. Worth repeating again and again and again. Actions speak louder than words but words inform and inspire actions and connect those whose paths would otherwise never cross. Closing libraries cuts off this access to information, and withholding information is a form of social oppression.

Thirteen public libraries have been damaged or destroyed in Gaza. The fate of others — those part of cultural or educational institutions – is impossible to clarify. One which remains standing at the time of writing is the Maghazi Library, described by Shahd Alnaami as ‘not just a library; it is part of my identity…The occupation is targeting our minds and our bodies, but it does not realise that ideas cannot die. The value of books and libraries, the knowledge they carry, and the identities they help shape are indestructible.’4 In August, Spellow Library in Liverpool was victim to an arson attack in the far-right fuelled riots. A fundraiser started by a local library user set out to raise £500; they raised £250,0005. One of my most repeated anecdotes of the year comes from an afternoon in spring. As Environmentalist-in-Residence with West Dunbartonshire Libraries, I was standing outside Dumbarton public library five minutes before it opened. In that handful of minutes seven women, one baby and a teenage boy gathered, waiting patiently for the doors to unlock. A library is more than the books it holds.

*

1 https://www.theguardian.com/news/article/2024/jun/25/how-britains-libraries-provide-more-than-books

2 https://www.scottishbooktrust.com/articles/why-are-libraries-important

3 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c30np8re5rqo

4 https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/12/14/gazas-libraries-will-rise-for-the-ashes

5 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cgl2z7xzw68o

*

Visit Christina’s website here. You can also follow her on X and Instagram.