Looking back on Apple Day at Wakelyns farm, Tallulah Brennan reflects on growing trees and building bridges.

As we are approaching Wakelyns farm, our taxi driver tells us that he has dropped off many visitors here over the last 15 years. He says that after one job, he was offered a little tour of the farm, where he learnt about Emmer, an ancient ancestor of durum wheat. It is the farm which leads us to talk in friendly, yet chaotic sentences about wheat, pesticides, and gluten intolerances, as the taxi takes us across the flat terrain of Suffolk. As strangers here, to hear the familiarity and fondness for where we’re headed is a comfort.

The next day, ‘Apple Day’, in the Wakelyns calendar, is perfect: an almost entirely clear sky, save for a few clusters of clouds staying low on the horizon. The journey from our home in Sussex, to Fressingfield, Suffolk, is not straightforward, nor cheap, but this says a lot about my feelings towards a good apple. We have come here to learn more about apples and agroforestry, to discover new fruits, and learn about the people growing them.

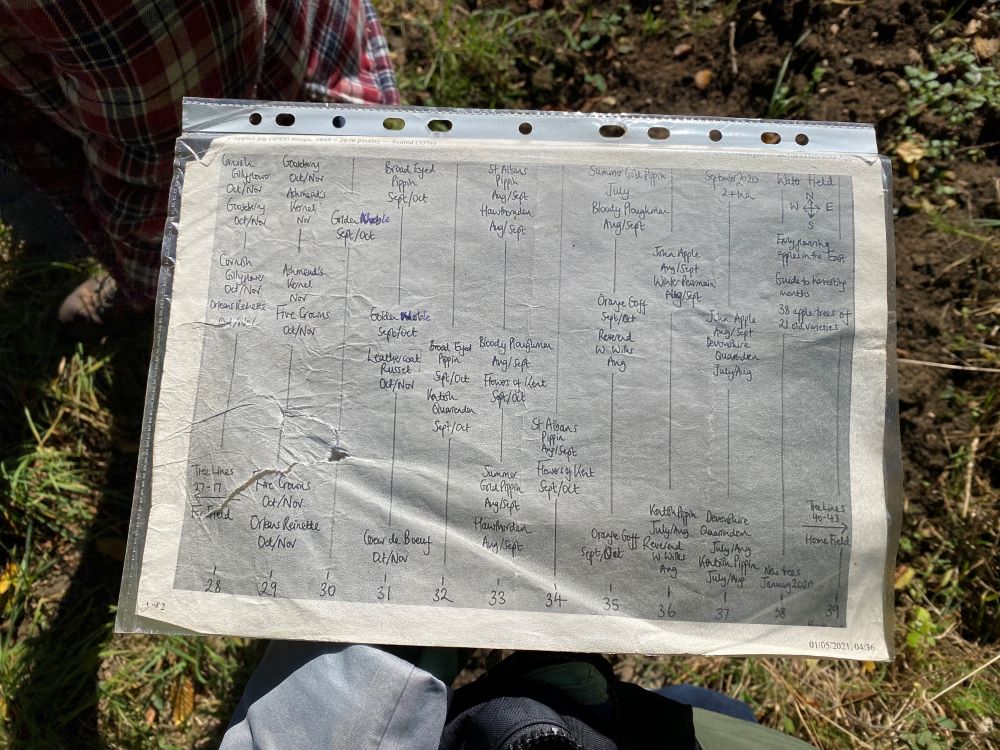

The first thing on the agenda is an ‘apple walk’. We listen to the dos and don’ts of pruning, we learn about apple tree diseases, and how to foster the traits of organic farming. On the second half of the walk, I notice the plastic sleeves our guide is holding, and show enough intrigue that he hands me one. The names I read from the handwritten map in front of me, Five Crowns, Orleans Reinette, Falstaff, Bloody Ploughman, are mostly unfamiliar. There is no point feeling sad for the years of not knowing, and so I keep directing excitable looks at my partner, who always returns them. I am thinking of the night before, when we walked home in the dark from the closest village, discussing which five trees we would prioritise for our garden, passing gardens already full of them.

The days we spend at Wakelyns are marked by a totally paradoxical mindset: thoughts about the future are constant, whilst the natural feeling of peace here pulls me into the present. My broodiness is intensified. As we are shown around, I have this lingering idea of a tiny, soft hand in mine, the other just waiting to pull the low-hanging ripe apples from the trees. Then, when we find the little Orange Goff apple on the stall table at the farm, I can see the potential of little teeth marks, of getting to eat what a child’s mouth cannot finish. As we wander the alleys, I cannot help but think, at least our child will know that caraway-ey, sweet and tart mouthful of the Ashmead’s Kernel.

In the morning, with our window propped open to listen to the birds, I try to loosen the grip that broodiness has on me, and start to think of this imaginary child as someone, or something, more worldly. Something that extends beyond ‘my’ or ‘our’ family. Of course I would like to hear the long names of these fruits struggling their way out of the mouths of my prospective grandchildren, but that would do very little to disturb the injustice of every other child’s unknowing, every other untingled taste bud.

Much like I struggle to identify what it is that makes a Leathercoate Russet or a Lord Lambourne so delicious, I struggle to articulate why exactly it is I need others to experience these apples. I belong to a generation for whom choice and freedoms and luxuries seem endless. ‘We’ve never had it so good.’ So why does everything feel so monocultural, so lacking in liveliness? Why is it only here at Wakelyns that I feel I am finally exposed to real diversity and choice? The crunch of the apples is unlike anything else. The smell they hold when they are in your hand, straight from the tree or not, is like fresh air. After comes the health of the soil; the care that went into this whole project in one delectable bite. We’re all searching for more, but more is here, in an apple. Or rather, more is found in these many apples, seemingly endless in their variety.

*

Once we have seen all there is to see at Apple Day, we take off for a walk around and beyond the farm. As we trace the edges of Wakelyns, we come to a cleared section of the bushes. We clamber over what appears to be some kind of makeshift bridge. A narrow, wooden pallet which is charmingly covered in moss, and positioned downwards and off-kilter, so I take care not to slip. A day later, when we are home from our trip to Suffolk, my partner scans the QR code which was taped to a piece of wood stuck in the ground nearby. The family who own Wakelyns have, over the past few years, built bridges around the farm’s edges, creating permissive paths for the public, to allow for greater access to the farm. One of their neighbours, however, took away this particular bridge, not wanting to encourage people to walk the paths near their property. After the initial frustration, it is the sadness which stays. What is lost by the chokehold of differentiating between what is ‘mine’, ‘ours’, or ‘yours’ — as if nature could ever respect such a differentiation? Later in the evening, we come back out to see the sunset from a break in the hedgerow we had scoped out on our afternoon walk. This view, and the noise of the jays which accompanied it, I remind us both on the way home, would be impossible without this makeshift bridge.

Returning to Wakelyns, through the path that some in this area would prefer us not to tread, the volume suddenly turns up. Out on the roads between the farms nearby, the world is silent. No engines, but very little animal life either. We see birds, we even see a hare and a deer, but the birdsong is unnervingly absent, and the animals we spot are making their way along only the edges of what are overwhelmingly barren fields. The path back to Wakelyns however, is much denser, and our world becomes crowded again. The shrubs and hedges are unkempt, and if we look up, our view of the sky is obstructed by the branches of the trees around us. We take recordings of the birds, just in case we are in the presence of an owl without knowing it. Being amongst the apple trees, walking along these paths, I am present in a way I rarely get to be. Life doesn’t feel monocultural: it feels calm, yet teeming with the possibility of life, when it is given a chance to thrive.

As I write about Apple Day, looking through my camera roll, and re-listening to the recordings I made, I am painfully aware that devices enable me to be everywhere at once, and yet I am only interested in being back on the farm. This trip is bittersweet. My partner found his new favourite apple, a Leathercote Russet, and I was reunited with one of my favourite things in the world, the juicy flesh of the Ashmead’s Kernel. “Do you have apple trees?”, asks a man who hovers over the map I am holding, back on our first apple walk. Before I can open my mouth, perhaps faltering from some sense of the feebleness of my response, my partner replies: “We’d like to, when we get our own place”. Most people on this walk seem to be growing apples already. They have land, and they have experience. We are here out of a desire to experience the abundance that most of these people already live within. It is a funny feeling, to have a taste of what you would like from the future, living with its lack in the meantime.

We have been home for a day, and missing the distraction of birdsong, and the swooshing of the trees, my mind is taken instead by the removed and replaced bridge. It is now that I start thinking of the other bridges that have been removed from our lives, and how many I know are worth crossing. All that we are excluded from; all of the apples most of us never know exist. I want to stop thinking about lack, and so I concentrate my mind instead on the smell that lingered in the air — the sweetness that exuded from the windfall apples, nectar for the birds, badgers, foxes and mice. I imagine I am back there, taking deep breaths of the perfumed air, reminding myself that the future is already here — for a small number of us. And if that is so, then it is bridges — of the kind strong enough to conquer both ignorance and the desire to exclude — that we must build.

*

Tallulah Brennan is a writer whose heart lives in Yorkshire, but is currently found in Sussex. She has written for climate magazines such as Where the Leaves Fall, and contributed to organisations like the Oxford Real Farming Conference. Her writing addresses connection to nature, and issues of access and inequality within an environmental and land justice lens.