Reforestation, bread babies, and owls from the underworld: Honey Davis-Wilkinson tries alternative living in the Andes, accompanied by her 35mm camera.

In 2008, two British women set up an eco village in Equador called Rhiannon Community, named after the mythical Welsh goddess. It’s situated in the Andes Mountains, at an altitude of 2,650m, one hour’s drive from Quito. The motto at Rhiannon is “Otro mundo es posible”/ “Another world is possible” — a life sustained by off-grid energy, rainwater collection, waste recycling, reforestation, organic farming, cross-cultural exchange and cooking and eating together. I recently stayed at the community for a few weeks and documented the trip on my 35mm film camera.

I arrived to a circus show, plus moussaka, beetroot brownies and a birthday being celebrated in four languages (English, Spanish, French and Romanian). It was a wonderful initiation — lots going on and minimal focus on the newcomer. Under a sky of shooting stars and a smiling horizontal crescent moon, I walked to my adobe cabin for a dream-filled sleep.

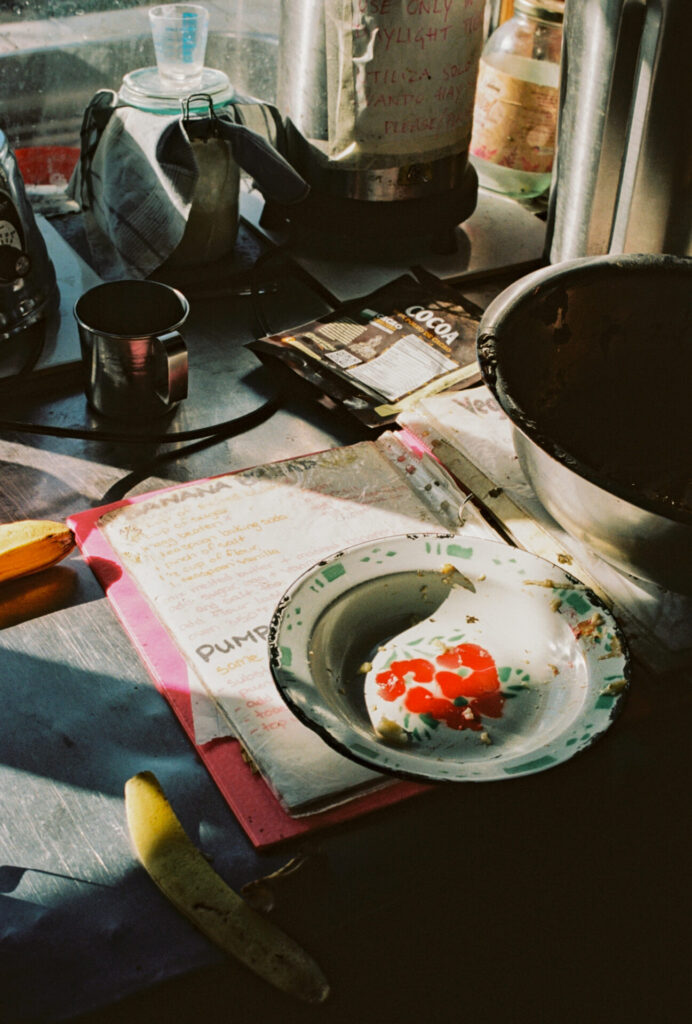

In exchange for three meals a day and a bed, the other volunteers and I would work for five hours a day, five days of the week. We cooked and helped make a new building out of adobe and old bottles (which became windows in the adobe walls). We also fed the cat, dogs and donkeys and did laundry. I was slightly worried about cooking for 15 people in an unfamiliar kitchen with no fridge and a lot of dried goods needing overnight treatment. The nerves vanished thanks to 12-year-old Satya — Sanskrit for “truth” — one of the two children living permanently at Rhiannon. One evening, I found Satya cooking for everyone with the stereo turned up full blast. When I asked if she wanted an assistant she politely declined and we had a grown-up conversation about why teenagers have mood swings. She prepared the meal effortlessly; I needed to stop worrying.

As I got into the swing of things at Rhiannon, I weeded and watered, harvested vegetables, made compost, collected mulch for the eco toilets and sorted seeds — including corn, plum, beans and heirloom melon. Our free time was filled with card games, sewing, hide-and-seek, dancing, plus drinking games, guitar-playing and singing. We also featured in a film directed by Arundel, who is the other inspiring child living permanently at Rhiannon, named after the “eagle valley” in West Sussex.

We had a tobacco ceremony – soliciting the spirits for acts of kindness. And a lot of bread was made. There were quimbolitos, pastry speckled with raisins and steamed in an achira leaf. There were also guaguas de pan (Ecuadorian bread babies) for Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Plus vegan French toast, Romanian cabbage pies and sweet-and-sour dough (sourdough bread with cinnamon, raisins and brown sugar).

I saw lots of geckos and birds, including the huiracchuro (golden grosbeak), mockingbirds and hummingbirds, such as the violetear. But it wasn’t all sylvan beauty. There was water theft (farmers illegally diverting water into their reservoirs, reducing the supply to a trickle for other residents). The Ecuadorian Post Office is now defunct. And local buses screen films en route – strange and transit-inappropriate movies. On one bus ride a film called Unstoppable played, a disaster thriller about a runaway train; not for the faint-hearted on the cliffside local roads. There was also a gory Second World War film about a Finnish soldier turned gold-prospector who was fighting off a brutal, murderous SS unit. Family viewing! But, while Trump winning the US election circulated the news outlets and socials, I relished the days in this alternative reality.

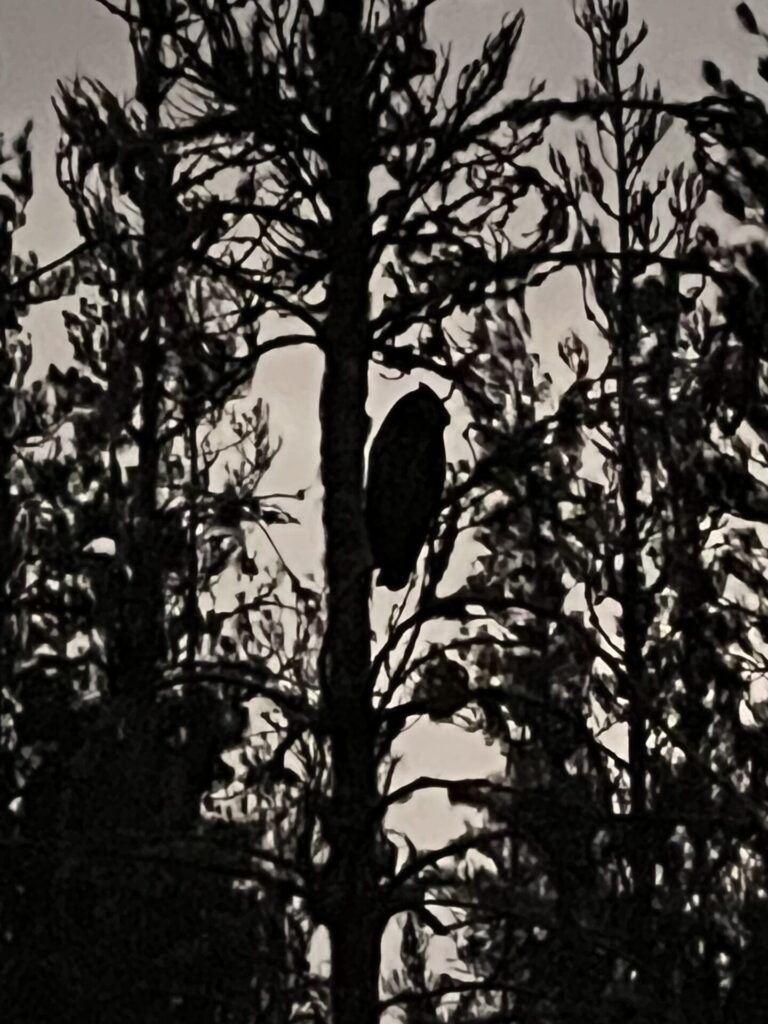

On my final evening in Ecuador, eight-year-old Arundel and I walked to a nearby pine forest with the intention of seeing a specific owl. This had been my dream since day one at Rhiannon. I wasn’t particularly hopeful – the dogs had joined us and were barking loudly. But it didn’t matter because everything felt magical under the light of the Beaver Moon. I suggested we head back, but Arundel wanted to persevere. I followed him down a less-trodden path and, as if on cue, an owl soared over us and perched on a tree. And not just any owl, a Stygian owl – a big bird with piercing eyes, its name connecting with the River Styx, the underworld waterway in Greek mythology.

After I got back to the UK, I found out that Arundel had set up an owl business, taking volunteers to the pine forest with the possibility of seeing the other-worldly Stygian beauty. It was $2 for the experience and a $1 refund if the owl was a no-show. Here was a young man achieving the perfect work-life balance.

*

Visit the Rhiannon Community website here.

Honey Davis-Wilkinson is a photographer. You can follow her on Instagram here.