Simon Costin, the founder of the Museum of British Folklore, on the work of the visionary English Artist, Barbara Jones:

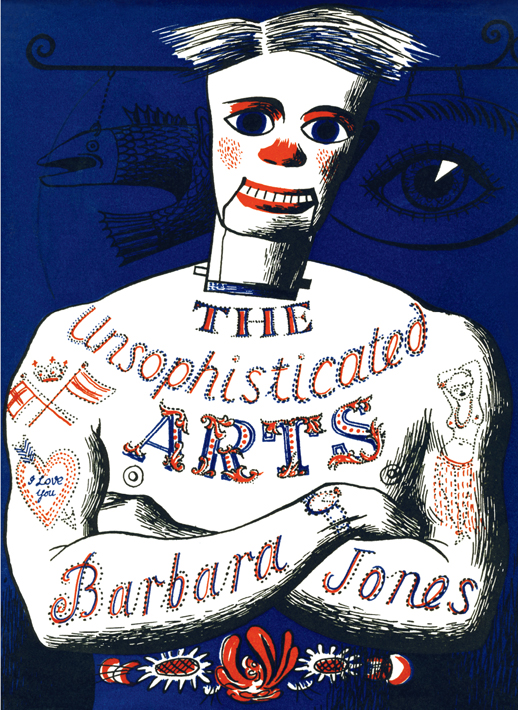

In about 1989, knowing my love for things quirky and British, my friend Graham Ward showed me an immaculate edition of The Unsophisticated Arts. I was immediately struck by the strangeness of the character on the jacket, what appeared to be the tattooed torso of a sailor, not with a human head but with that of a ventriloquist’s dummy. The content of the book fired my imagination too, and twenty-four years later I find myself at home surrounded by many of the objects Barbara Jones wrote about: fairground art, waxworks, Punch & Judy figures, stuffed animals, corn dollies, fireworks, shell-encrusted vases and, yes, a ventriloquist’s dummy.

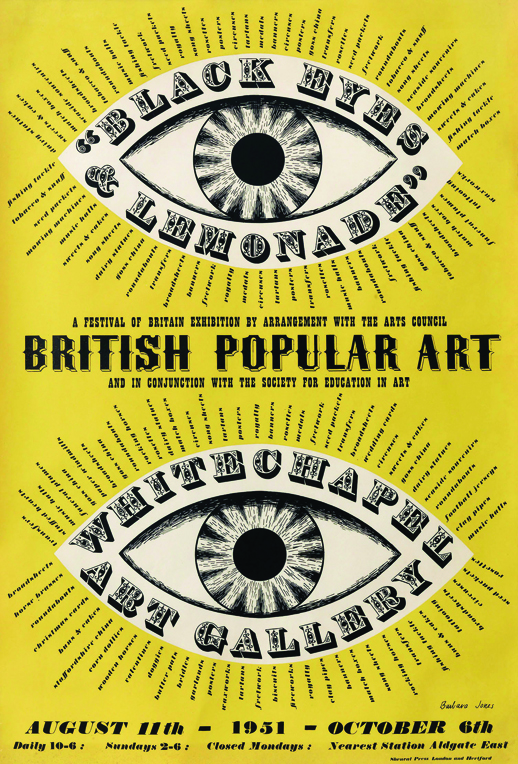

What I wouldn’t give to be able to hop aboard Mr Wells’s Time Machine and set it to arrive at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1951, so I could pay a visit to the ‘Black Eyes & Lemonade’ exhibition which Barbara Jones organised with Tom Ingram for the Festival of Britain. In many ways this book and that exhibition are the same thing. They both represent a drawing together of the everyday artefacts which Barbara Jones had been surrounded by growing up in Croydon, and both presented these objects in ways which had never been seen before.

But what exactly was it that she curated for the Whitechapel exhibition and illustrated in The Unsophisticated Arts? Is it folk art? Is it vernacular art? Is it pop art or outsider art? Tom Ingram, co-curator of Black Eyes & Lemonade, struggled to find a workable definition of the art on show in 1951, and in the accompanying exhibition catalogue Barbara Jones herself wrote that ‘we have not been able to find a satisfactorily brief and epigrammatic definition of Popular Art.’ Some of the objects Barbara Jones collected and arranged already had relatively long folkloric histories, such as horse brasses, corn dollies, canal boat artwork, ships’ figureheads, and the pearly King & Queen outfits. But these were shown alongside more contemporary, post-industrial advertising devices like the Idris Talking Lemon, beer mats, pest control adverts, shop posters.

In so doing she gave ‘folk art’ or ‘popular art’ a cultural currency, she made it relevant, exciting. And by putting the machine-made and the hand-made side by side, she blurred the boundaries between what was considered art, liberating a way of seeing that continues to widen our appreciation of the ordinary, the everyday.

She may not have seen it as such at the time, but on one level what Barbara Jones displayed was a cabinet of folkloric curiosities. These early Wunderkammer – ‘wonder rooms’ – were filled with objects which could not be categorised. For the exhibition – and one assumes for the chapters of this book – she did finally decide to set up a ‘series of arbitrary categories’. But these, she insisted, reflected ‘most forms of human activity without creating bogus sociological implications’.

Her instinct for the arrangement and display of objects was long-standing. In 1948 she painted panels for the Design Fair showing collections arrayed across a series of shelves and beneath glass domes. A display panel for the BBC from 1950 has a cabinet, doors flung open, with a series of niches housing a different musical group and flanked by two ornate display stands.

There is much to be learnt from the way in which Barbara Jones presented the work in ‘Black Eyes & Lemonade’ and The Unsophisticated Arts. She encourages us to re-evaluate everyday design and to see the liveliness and energy it contains. Describing the exhibition as ‘bold and fizzy’ and the content of her book as ‘unsophisticated’, we are able to contemplate the vernacular in all its audacious glory through Barbara Jones’s extraordinary eye. The sheer bravura she applied to her selections, the way in which visitors where allowed to interpret the material, the way in which she navigated the demands of the Society for Education in Art (who originally proposed the exhibition), her playful and striking graphic work for the poster, catalogue and throughout this book, and finally her sheer force of personality all meant that what was produced was a singular and unapologetic vision of Britain.

Simon Costin is an internationally respected art director and set designer. Since leaving Wimbledon School of Art, where he studied Theatre Design and History of Art, he has worked with numerous leading fashion houses, including Lanvin, Hermes, Yves Saint Laurent, Margiela, Gucci, Faberge and Alexander McQueen. Simon’s work has also been displayed in many exhibitions, including a forest in Argyll, the ICA in London and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He is the founder and director of the Museum of British Folklore and is currently writing a book about seasonal customs and traditions in Britain.

Black Eyes & Lemonade, co-curated by Simon Costin, is on show again (until September), at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. More information can be found here.

The Unsophisticated Arts has just been republished by the ever reliable crate diggers at Little Toller Books. Buy a copy here.