by John Hillaby

from Country Fair, April 1952.

I suppose you could blame Yeats, the poet, for a lot of my theories about this fishing business. I went to see him in Sligo when I was just beginning to get my wrist muscles adjusted to a fly-rod. I was a youngster; he was a white-haired old man, famous, friendly, fanciful, and interested, heaven knows why, in the lad who kept pestering him about the way of a trout with a fly.

He said, I remember, that a fisherman was of the old aristocratic line, like a man with a horse or a hawk or a good dog. He meant there was something in the lonely wisdom and skill of the craft that was related to the Renaissance tradition. I know what he meant.

I felt strongly the other day when I was watching a hatch of Dark Olives scrabbling out their larval shucks and gliding downstream, trying to set their leaden wings against the rigours of wind, water and life newly awakened. I knew what those flies were. I have tied dozens to Skues’ dressing but, more important, I know now that I can become one with the stream and its life and catch fish in their own element and with their own food. Points of identification with the objects of our affection such as these are important. It’s better to be able to spot the difference between a dun and a spinner on the water by the opalescent flash on the wings of the latter than to have half a dozen Leonards or Hardys on the rod rack at home.

Years later I caught perch with the two lengths of tonkin cane and a greenheart top before I turned to that vibrant composite called split-cane; and in just the same way my tonkin carried thirty yards of plaited double-nought silk thread before I learned to handle that pilant and all powerful lash called a double tapered fly line.

It was then and only then that I discovered that the taper of the thick line extended the taper of the rod, and that the taper of the cast perfected both until I had between fingers and thumb an instrument diminishing from the thickness of the cork grip almost out into infinity – or at least to a point within the hair’s breadth of the trout’s neb, which I count as near heaven as mortals can go. You know, fly gear really is wonderful stuff.

The way a good rod first flexes and then extends its muscles as the line quickens, tightens, rises off the water and does figure eights in mid-air is one of the miracles of humanly applied dynamics. It never ceases to amaze me. But if the rod is the instruments, the sensitive extension of the nerve and muscle, the fly is stimulus, the very fibre of the emotional gland, and as I watched the Olives sail down what is now my adopted southern river, I thought of my days when I first tried to sort out sense from the tangled hosts of the world of flies. Hang it, there are thousands of them!

I know that there are skilful men killing fish on our rivers today who imagine that a Blue Upright is a kind of bastard half-brother of the carnivorous flies which sneak into dustbins or air their green behinds in the sun, but nothing indeed could be further from the biological facts of the matter. The water-born or aquatic flies are far removed from the parents of pallid meat-boring maggots as an earwig is from a moth: they represent quite different orders (let alone families) of insects. Unfortunately the aquatic tribe are a jumbled assemblage in themselves and represent no clear-cut or easily definable group.

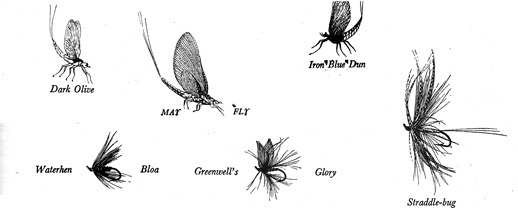

Broadly speaking they fall into two classes: the sedges, alders and needles with wings like a pent-house roof, and then upright-winged mayflies which have a complicated life-history. I refuse to discuss stoneflies and midge-like creatures, holding that they were sent along just to complicate matters.

The art of casting a trout fly (dry) above and over a fish so he imagines it is another helping of a meal he has been feeding on is no less difficult than flicking another fly (wet) above the fish under the water so it imagines (one hopes) that it’s a natural fly in difficulties. The principle is the same: natural representation.

Unfortunately, we don’t know what a fly looks like to the trout. We know they have monocular vision: that is to say, one glassy cornea can concentrate on a mid-morning snack in the shape of the water, whilst the other is warily watching a dunder-headed fisherman who foolishly imagines he looks like a tree. We know that water distorts the image of the fly, as I once found out in the bath with the aid of one of those breathing-tube affairs. From below I discovered that the hackle points of a floater break up the meniscus of the water into a multitude of facets prismatic fire of a diamond, and what that effect must be like in an unsmooth stream I leave to the imagination of anglers who are optically minded.

It is for this reason that there are schools of fly-tying more complex than all the divisions of the art world, Picasso and all. Surrealists on the Clyde and Tummel decorate their long, raking hooks with meagre wisps of hackle and dubbing; Yorkshiremen are fly-tying Impressionists who seek to suggest a jumbled fragment of an insect, swirling legs over tip in a busy stream. In Hampshire and the southern counties there are the exact representations, the piscatorial pre-Raphaelites who try to simulate the filigree transparency of flies’ wings with honey-dun hackles and pike scale. There are Cubists here and there with their square hackles, Vorticists, too, if you count Dunne’s “Sunshine” series. All effective artists and all sure they are right. See the full show in a dealer’s window.

My own views are betwixt and between. I don’t hold with those who fish the whole season through with nothing more than Greenwell or, in the south, an Olive dun, but I think it’s easy to become pattern-obsessed. I must confess that it’s some years since I put an artificial fly with wings on it, preferring all the graduations of the fur-bodied and partridge or landrail hackled insects for the glorious company of sedges including the grannom; and I think fishes feeding on Olives of all kinds can be tempted with a series dressed solely with cock or hen hackles and quill bodies.

And lastly, if I’m given enough seasons for experimentation. I think I might synthesise a confection of fur and feather to suit each one of the streams I know well. Just one! And I shall call my creation Beelzebub, the Prince of the Flies.

John Hillaby was a naturalist, a journalist and an enthusiastic walker. He died in 1996. Of his many books it is A Journey Through Britain from 1968 that we revisit most often.