Simon Goddard (Ebury, £16.99)

Reviewed by Pete Paphides

Thirty-three years have elapsed since the wildly prodigious Roddy Frame volunteered Aztec Camera’s most impressive song to date for release on Alan Horne’s Postcard label. And, before you even factored into the equation that this was the work of a 16 year-old, Just Like Gold was impressive. Cramming more chords into just over three vertiginous minutes than his idols The Clash had managed on the whole of their first album, Just Like Gold sounded like Love, if had Love grown up in a rainy Scottish working-class new town on a diet of white bread and magic mushrooms. “I don’t think I could improve Just Like Gold in any way,” Roddy proudly told the woman from the NME. “I spent a long trying to sound unclichéd. There’s no chorus in it. Nothing’s repeated.”

A couple of months ago, I interviewed Roddy. Now 50, he is, in many ways, a more reasonable man than he was in his teenage years. But there are some things you have a duty to never forget. The two singles that Aztec Camera released for Postcard have never been reissued or licensed for use on any subsequent records. Neither will you find them on iTunes or Spotify. For Roddy Frame, Just Like Gold and its successor were perfect mementos from an unrepeatable moment in time. Such stubbornness also acts as a tribute to the man who Roddy calls his Warhol. A self-contradicting ideas man who defined himself as much by what repelled him as excited him. A schemer whose ambition far exceeded the scale of his operation. When I met Roddy, he told me a story concerning an exchange he had a couple of years after Postcard went under, with “one of the guys at Rough Trade”, shortly after Aztec Camera had signed to the label. Called to one side for a gentle reprimand over some reported comments about Rough Trade’s distribution capabilities, Roddy was told, “we’re not in the business of making pop stars here.” Roddy’s retort was pure Alan Horne: “I’ve noticed.”

At some point, someone was going to write a book about the history of Postcard Records and barely a chapter into Simply Thrilled, you realise it would have been a tragedy if anyone other than Simon Goddard had taken on the job. Goddard is perhaps best known for his two Morrissey/Smiths books Mozipedia and Songs That Saved Your Life – but without any apparent contrivance, Goddard’s vernacular seems to have descended through the rabbit hole into the thriftstore Wonderland of Glasgow in the late 70s, not as the ruling tribes of neds or “juvenile hobgoblins of local gang The Maryhill Fleet” might have seen it, but as Horne and Edwyn Collins saw it. Way before the arrival of Postcard’s remaining roster – Josef K, Aztec Camera, The Go-Betweens – this often reads like an extended treatment for a buddy movie fully befitting of the “preposterous” in the subtitle. And, of course, in any buddy movie, there has to be moment where eyes meet eyes and animosity blurs into curiosity, which in turn morphs into a mutual dependence. The moment where the gangly offspring of arty middle-class Mr and Mrs Collins meets Alan the Diana Ross-and-Velvet Underground-obsessed son of an ICI Factory worker:

“Somewhere in the back of his head, Alan remembered the face. It was a gauche face attached to a proud neck, poking out of a checked shirt, above a couple of wiry legs in blue jeans… It was a funny face. Not funny ugly or funny weird, but funny in an odd jack-in-the-box readiness that showed its springs even when the mouth was shut. Alan chose this moment to flip it open.

‘That’s a shit shirt.’ He jutted his chin at Edwyn’s checks. ‘Who’d you think you are, John Boy Walton?’

‘Shut your mouth, fat boy!’

Alan’s heart flip-flopped. Edwyn blazed with wonder. The air between them crackled with silent static and Detroit strings.”

Goddard’s interviews with the extended Postcard family yield an absurd yarn for pretty much every page of Simply Thrilled, but his decision to forsake direct quotes is a shrewd one. His authorial voice is akin to that of the narrator in the Disney animations of Winnie The Pooh, merely reporting goings-on among a most unusual group of people that seem no less remarkable for the fact that they happened a so very long time ago. As he concedes from the outset, some people’s memories contradict each other – for instance, Robert Forster flatly refutes having had long hair and smoking dope when he and fellow Go-Between Grant McLennan first encountered Alan – but then, these are the anecdotal add-ons that come with any story that has been finessed over decades.

And in the case of Postcard, the business of separating myth from fact is made more complicated by the fact that, even at the time, fibbing was part of the perpetual wind-up. Perpetually amused by everything, the young Edwyn takes extra-special delight in telling people that Alan’s own band Oscar Wild have a song called Woah, Woah, Dustbin – and reminding Alan that his own musicianly ambitions “began and ended in a village hall in Troon, trembling before a local chapter of Hell’s Angels which, by the time Edwyn got hold of the story and inflated it into the weather-balloon-sized farce he desired, ended in something approaching Altamont on the South Ayrshire coast.”

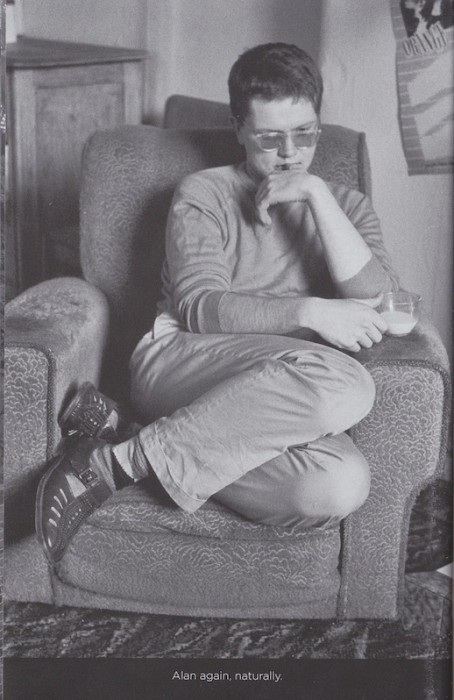

Photograph by Paul Slattery

Though Goddard doesn’t say it, it seems that the engine of the pair’s friendship in the early part of the book is the gobby Alan’s simultaneous delight and mortification that he had finally met his match. His first visit to Edwyn’s parents’ house in Northwest Glasgow is yet another scene screaming out for celluloid treatment:

“Morning brought a bigger shock to Alan’s system when they went down for breakfast and were greeted by Edwyn’s mother, Myra

‘Morning Edwyn!’

She wasn’t like any mum Alan had ever seen before. She seemed too young, too pretty. Too much like Wendy Craig, from Butterflies.

‘Hi mum, this is Alan,’ smirked Edwyn. He’s a homosexual Nazi.’”

Personally, I can never read enough accounts of young people who, marginalised by the prevailing sensibilities of their parents’ generation and, indeed, most of their own generation create their own culture. To read Simply Thrilled is to be reminded of the fearlessness of all the teenage outsiders who, travelling in the slipstream of punk, converged together to form micro-tribes, which more often than not, resulted in bands who didn’t quite know what they were. It’s no surprise that, two albums into their career, Derry’s Undertones clapped eyes on Orange Juice and immediately recognised them as one of their own. Most post-punk bands weren’t shocking. They were too awkward, too self-conscious to wear clothes that upset their mums and dads. Those, like Edwyn Collins, who dressed up, went about it rather like seagulls at the seaside, picking through the scrag-ends of whatever most folk had left behind.

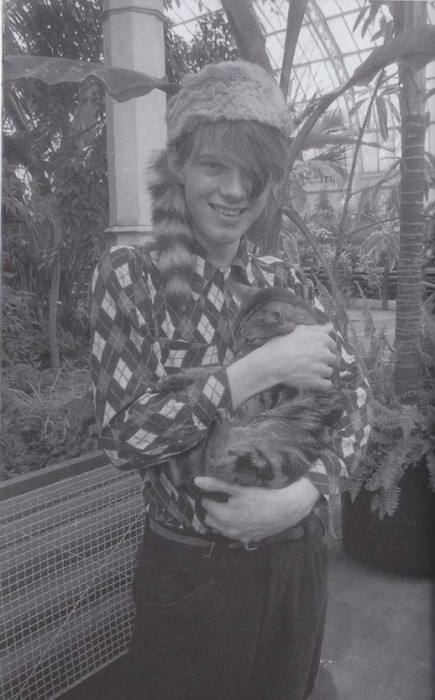

Photograph by Francesco Mellina

The atmosphere of post-punk, pre-vintage Glasgow is beautifully captured in Goddard’s description of Paddy’s Market with its smell of “something over-boiled, something which may once have been meat, something definitely more dead than alive… A cloudy broth of humanity sloshing its tide from one end of Shipbank Lane to the other. There was nothing that mankind and its machinery had ever made which could spoil the taste of such a broth. There was no vase so cracked, no toaster so plugless, no kettle so crusted with the lime of half a century’s hard-water brewing, no shirt so buttonless, no suit so unloved, no felt hat so unwearably olive, no left shoe so alone without its right, no book so stained of page, no record so sleeveless and greasy, no album cover so vandalised by crayon, no dining fork so twisted, no spatula so melted, no saucepan so scorched, no object however small so begging to be otherwise consigned to the nearest skip which wouldn’t have added something to the flavour of Paddy’s market.”

Also unearthed at Paddy’s Market, the drumming picture book cat – the visual calling card of once-loved but long-forgotten Victorian illustrator Louis Wain – now became the visual calling-card of Postcard Records. From this moment on, the truth most clearly highlighted by Goddard’s book is that: (a) every emerging scene needs a loud-mouthed, would-be impresario with an aesthetic and a plan; (b) everyone in any emerging scene wants to impress someone who has an aesthetic and a plan. According to Goddard, Alan Horne’s aesthetic was an inadvertent source of torment to him. In what becomes something of a leitmotif, every new Postcard release – be it the the hyper-adrenalised opening shot of Orange Juice’s Falling & Laughing or Josef K’s It’s Kinda Funny is placed on the turntable and found wanting next to The Velvet Underground. In Horne’s mind, each band he signs should sound like The Velvet Underground at a different point in their career to that represented by any of their Postcard labelmates. But by the time he signs Aztec Camera, Horne is running out of Velvet Undergrounds, until it occurs to him: “Has anyone ever told you you’re the eighties version of sorta supper club Live At Max’s 1970 Velvet Underground?”

Other leitmotifs are similarly inspired, perhaps no more so than the one about Robert Forster and an X-Ray of Nicolas Roeg’s knee. That the main participants of Simply Thrilled have survived to tell their (conflicting) sides of the story is a minor miracle. The image of The Nu-Sonics having to spontaneously play Showaddywaddy’s Hey Rock’n’Roll to appease a baying crowd of Glaswegian meatheads is as terrifying as it is funny; the return journey from London back to Glasgow conducted in driving rain in a car whose windscreen had been smashed to smithereens further fattens the myth. It’s a testament to Goddard’s masterful storytelling that – once you’ve hooted at the last preposterous tale in Simply Thrilled – the myth looms larger than ever, the music a little more breathlessly brilliant than ever before.

Simply Thrilled is available in the Caught by the River shop here at the special price of £15.