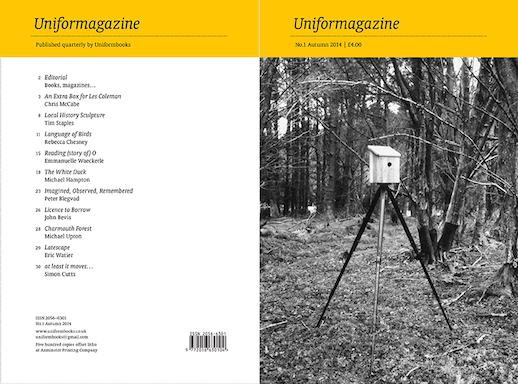

One of our favourite publishers, Uniformbooks, are launching a new quarterly magazine, Uniformagazine, and to mark the occasion, here’s something founder Colin Sackett wrote back in 2001. An essay originally titled “Ask the Librarian… a preamble concerning the ‘atmospheres’ of colour, height and subject”, and published as the introduction to the anthology The Libraries of Thought & Imagination, Edinburgh 2001.

“The first collection of books that I can recall as a singular accumulation—that is to say, a selection gathered together as a ‘resource’ for a particular concern—was a glass-fronted cabinet containing several shelves of books on the subject of physical geography. This was housed in the corner of a school classroom devoted to the teaching of the geography curriculum, at ‘ordinary’ (11–16 year-olds) and ‘advanced’ (16–18 year-olds) levels. Open access to the books in the cabinet was granted to those studying at the advanced level, encouraged by the code, that “knowledge is not remembering facts, but knowing where to find them”—an endorsement of both the inquisitive motivation of the auto-didactically inclined, and of the practical advisory role of the librarian.

My own ‘use’ of the books in this small and specialised annex to the main school library consisted usually of ‘flicking-through-looking-at-the-pictures’. As I remember (with hindsight), most of the books were published in the period from the 1940s until the 1960s, and while only being able to remember a few particular titles, I can vividly recall the tone and atmosphere that surrounded the collection (or at least, my impression of the collection). Several titles were from the Collins ‘New Naturalist’ series, mainly published in the 1950s, with their (then) high-quality colour plates; often of strange colour balance, curiously retouched skies, and sometimes distressingly out-of-register printing. There were books that dealt with the subject of ‘field-work’, describing a didactic purpose and methodology of observation ‘out-and-about’ in the landscape. Memorably, one or two of these field study titles were illustrated with topographical line drawings, where the line of the landscape and the hand-rendered textual ‘legends’ were wholly integrated. As drawings they sought to dispense a particular function, acting as an aid to the understanding and ‘reading’ of the landscape, as opposed to depiction for artistic purposes—the brevity of these compositions more like transcription than impression.

During the twenty-five or so years since I last examined this collection of books, I have bought copies of many of the titles for depositing amongst our own bookshelves, not as a distilled memento of that selection, but as separate parts of a broader and active personal collection. For instance, books illustrated by Geoffrey Hutchings (responsible for the line drawings described above) sit occasionally next door to childrens’ books illustrated by Edward Ardizzone—near contemporaries, but draughtsmen of conflicting purpose. Similarly, whereas titles from the ‘New Naturalist’ series would ordinarily be placed within their own subject category—birds with birds, botany with botany, etc.; my half-dozen or so are placed together as a uniform group, the meaning and purpose being that they represent and illustrate a particular historic manner of publishing, both editorially (as a series) and physically (as uniform objects). The coexistent, and equally justifiable logic of both of these systems of categorisation—by subject, or by type—suggests that there are, in effect, always two (or more) possible versions of order using one and the same thing. One of the ‘more’ versions being the possibility of practical dis-order: manifest paradoxically in the apparent order of a shelf of mixed-category books arranged by height or colour.

I remember noting at an early age, that to search amongst the shelves of the junior library for a book on a particular subject, might present only an incomplete selection of the available holdings; a further gathering of ‘oversize’ books could be examined elsewhere. Certain areas of illustrated non-fiction dominate these shelves: art, natural history, regional geography, etc.; while fiction is published almost entirely in ‘normal-size’ formats—apart from scaled-up ‘large-type’ versions for the hard-of-seeing, who usually have their own exclusive library-within-a-library. The practical reasoning behind this segregation by format, is of course to avoid over-height shelving for under-height books; that books of the maximum height would determine the gaps between shelves, leaving irregular and wasteful airspace above the more common, smaller formats.

Another segregation, in the larger public libraries is the ‘stack’, a sometimes mysterious holding of older titles, again arranged subject-by-subject, but often requiring permission to be examined. It is as if both an historical and a geographical boundary exists between the holdings in the stack and those currently in the main body of the lending library. Given that in most public libraries there is an optimum number of titles that can practically be available at any time, and as new titles are acquired, the notional break-off point moves chronologically forward. Books that I examined in the stack of my local town library in the 1970s, that had been published in the 1930s and 1940s, would now have been joined by titles from the 1960s and 1970s; then part of the active lending library. The notable difference between the stack and the current, is therefore one of age—that the books in the stack contain old or out-of-date information, now superseded by newer publications on the same subject held elsewhere. Books on outmoded subjects would certainly be found in the stack—technical works about radio involving glass valves, for instance; or books on geology and earth science unwittingly absent of any mention of ‘plate tectonics’—while the majority of books required no justification or excuse for having been published thirty or more years earlier. However, with the problems of differentiating that which is still definitive or current from what is not, this demarcation and grouping based on publication date is the most logical and reasonable slimming-down method for an expanding holding of titles.

Very few people would divide their own books into pre-and post- a particular publication date; and very few people—apart perhaps from professional librarians—arrange the books in their homes according to the Dewey Decimal System of Classification. Further, unlike a public library, very few people actually possess collections of books that range across the scope of subjects defined by such a complete system. The most common, the average domestic collection of books, is probably imbalanced towards fiction and novels, and these might be arranged alphabetically by author; or chronologically, as read (the earliest sometimes separated as a personal ‘stack’); or by publisher (the old orange-spined Penguin, the green-spined Virago) or genre (crime, horror, romance, etc.); or not arranged particularly at all. In addition, a non-fictional interest might form another grouping that would demand a practical placing within the house—recipe books, for example, housed separately in the kitchen or dining room; and if extensive, by country or course: Indian, Italian, soups or desserts. Likewise, erotica might find its most comfortable location in the bedroom, while the lavatorial reader is a niche-genre of its own.

In this house the bookshelves in the downstairs front room accommodate books on art, history, literature, music, philosophy, etc.—broadly cultural subjects. While in the back room, there are books on birds, gardening, geography, weather, etc.—the natural world, as such. The division is as much practical as it is thematic; the quantity of books divided with the bulk (and also the bigger, but not necessarily ‘oversize’ ones) in the front room. However, the classifications described above are not always definite—there being no need for them to be—and therefore anomalies and what might seem to be misplacings are many. Because it is a house, for living and working in, and the books are for using day-to-day, rather than a library or an office primarily for study or work, there is no imperative for a system of ordering and grouping beyond a familiar active use. For instance, a public library will usually separate the titles of local interest into a ‘local studies’ section, whereas our ‘local’ books are by subject, whether they are to do with topography, or architecture.

Upstairs, in what purports to be an office, there is another accumulation of books and printed material that is shelved, or piled, without any obvious logic or arrangement: source material, and books of miscellaneous subjects that are of particular interest in terms of design and format and production; catalogues and lists; typographical specimen books and material samples; dictionaries and other reference books. Common to this type of singularly practical, but seemingly haphazard collection of material, is the ability of the owner—or home librarian—to locate anything almost instantly.

A further distinction is often made between the already housed and the freshly acquired. In a public library new books will initially await the procedures and devices of registration, to then be shelved and labelled for a short period as ‘new acquisitions’. Domestically, the new and as yet unread might be grouped together, in some cases perhaps as ‘trophies’, but generally in anticipation of being both started—and finished. The book-laden coffee-table presents a complexion of the owners current interests, inasmuch as an entire collection offers a compounded view of previous interests—an historic complexion; although parts missing by ‘de-acquisition’ will present a manipulated and partial view. (It is an unusually stable individual that chooses to consistently resist the temptation to pare at an accumulation of books—to adopt a policy of complete acceptance of all past reading.) Consciously or not, the ownership of bookshelves is a constantly active licence for addition, arrangement and removal—the processes of editing inherent in the making of books themselves.”

Copies of Uniformagazine are available to buy from the Caught by the River shop here, priced £4.00