The chapel at Capel-y-ffin. Its crooked belfry follows the contours of the mountains behind.

The chapel at Capel-y-ffin. Its crooked belfry follows the contours of the mountains behind.

Richard King

High in the Honddu Valley in Powys, below Gospel Pass from which on a clear day it is possible to see the length of the Wye Valley, lies Capel-y-ffin, a hamlet that is little more than a scattering of properties: a farm, a former monastery and the chapel from which the settlement derives its name. A single-track road, hazardous in the mildest of winters, passes through the buildings and encroaches on the intimacy suggested by the adjacency of the farm to the chapel.

The road carries cautious traffic from Hay Bluff in the North to Llanvihangel Crucorney and its twelfth century inn, The Skirrid, twenty miles to the South. A short, arduous hike Westwards from Capel-y-ffin leads to the Silurian rocks of the Black Mountains, whose brooding contours prevents the sun from reaching the hamlet in the foothills below. To the East is the uninterrupted ridge of Offa’s Dyke. As one looks up towards the earthworks its presence so near the clouds seems ethereal.

Fifteen years ago I drove the twenty or so miles along the road from Hay towards

South Wales. We descended the pass from Hay Bluff and approached Capel-y-ffin then, as if in a vision, six white Cob ponies appeared suddenly, running together across the field near the monastery. Such was their effect on my subconscious I often reflect that it was at this moment, entranced as I was by their fluidity of movement, that I took the decision to move to Mid Wales.

For four years in the nineteen twenties the monastery at Capel-y-ffin was home to the peripatetic sculptor, typographer and craftsman Eric Gill and his extended family.

According to his biographer Fiona MacCarthy, Capel-y-ffin was the most inhospitable of the sites Gill chose for his continuous attempts at establishing an ideal of communal, artistic cohabitation:

“Of all his destinations Capel-y-ffin…. was by far the furthest off, the most remote, the wildest.”

Gill converted the monastery’s many dilapidated chambers into workshops and living quarters and there, however temporarily, created an environment where the distinction between work and play did not obtain. Although the practical difficulties of life in the Black Mountains often frustrated him, it was amidst this rural isolation, among the sheep, the rocks and clouds, that Gill designed his best-known work, the now ubiquitous Sans serif typeface, for the Monotype Corporation in 1926.

An English translation of ‘Capel-y-ffin’ is ‘Chapel of the boundary’ or ‘Chapel at the end’. In the churchyard of the Chapel are headstones carved by Gill. The graves lie at the edge enclosed by a low stone wall perimeter; beyond are open fields and hills whose distance from the Chapel is hard to judge. The gradient steepens and darkens towards the permanent horizon of Offa’s Dyke.

The interior of the small chapel includes a wooden choir and windows of sufficient proportion to allow the whitewashed walls to be bathed in sunlight. The stillness of the surrounding fields enhances the cell-like atmosphere. On the wall nearest the chapel door is a reproduction of a crucifixion ‘Sanctus Christus de Capel-y-ffin’, a gouache by David Jones, the Welsh poet, illustrator, calligrapher and artist who lived with the Gills at the Monastery from 1925 and who, for a short period was engaged to their daughter, Petra.

Gill was an influence on Jones, particularly in his calligraphy. In return, Jones considered the ‘Unconsidered artefacts, the little crucifixes on the forgotten gravestones, the holy-water stoups, small things done for realistic purposes’ of which the gravestones in the churchyard are an example, to be Gill’s most successful work.

It takes little more than an hour of exploring Capel-y-ffin to become aware of the strong sense of metaphysical energy encircling this secluded, magical site. The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams who visited the Honddu Valley regularly, often referred to what he called ‘thin places’ where the distinction between the physical and incorporeal is slight. The boundary alluded to in its name might easily refer to the manner in which the hamlet seems to stand between two worlds. At night under the clear winter skies we have recently been experiencing, Capel-y-ffin is set in radiance by the moonlight and appears, to borrow a phrase from Jones’ epic narrative poem In Parenthesis, under ‘starlight order.’

Although the climate may have been harsh, David Jones doubtless took comfort from the singularity of Capel-y-ffin as his weakened lungs drew in the mountain air. While resident at the monastery he painted and illustrated prolifically and later reflected that the landscape had allowed deeper understanding of his Welsh identity.

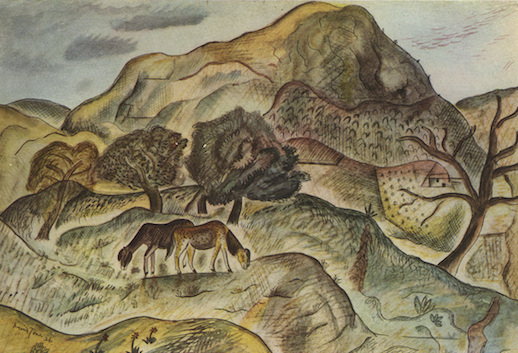

David Jones ‘Hill Pastures’ 1926

David Jones ‘Hill Pastures’ 1926

In the nineteen twenties Jones was attempting to come to terms with his experiences of the First World War. The reconciliation evaded him and the following forty years of his life were spent enduring and navigating successive bouts of mental and physical collapse.

Jones nevertheless found catharsis in writing In Parenthesis. The poem juxtaposes the horror of the Mametz Wood, in which he fought as an infantryman in the Royal Welch Fusiliers during the battle of the Somme, with allusions to landscapes from Shakespeare and from Welsh mythology, including those found in The Mabinogion, Preiddeu Annwfn (‘The Harrowing of Hell’) and Y Gododdin, a medieval Welsh poem written as an elegy for the defeat of the Welsh at the battle of Catraeth in AD 600.

The following passage from In Parenthesis describes the uneasy drift of time in Mametz Wood and might be equally apposite to life at its harshest during winter at Capel-y-ffin:

‘The sudden violence and the long stillnesses, the sharp contours and unformed voids of that mysterious existence, profoundly affected the imaginations of those who suffered it. It was a place of enchantment’

A front at Mametz was given the name ‘Acid Drop Copse’. As an undergraduate I was struck by this name and its similarities with a profoundly different sense of enchantment, one beloved of British psychedelic groups about to endure an altogether more benign, psychedelic, horror than that experienced by their antecedents of a similar age fighting in the trenches decades earlier.

There is a terrible symmetry to the lives of Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas and their fellow War poets who died on the battlefield, one that allows for a simplification, or perhaps even a reduction of their tragedy; as if their sacrifice at so young age can be mistaken almost as a form of romanticism.

Jones completed In Parenthesis in 1937, almost twenty years after the Armistice. Upon publication W.H. Auden described the poem, written by a man in his middle years, as “The greatest book about the First World War”.

As a year of commemoration draws to an end, to read In Parenthesis is to be reminded of the on going waking dreams, the unknowable, liminal thinness endured by those who survive. Anniversaries may be a necessary marking of history, but as the years recede the ravaging, psychological effects of war are harder to comprehend.

The beauty and isolation of Capel y-ffin, where Jones sketched and wrote and wandered the hills between worlds, is a reminder that for those forced to participate in its savagery, war is a permanent condition. And there is a richness from which to draw solace and memory within its haunted landscape.

In Parenthesis has been republished this year as part of Faber & Faber’s Poets of the Great War series.

Richard King is the author of How Soon Is Now? The Madmen and Mavericks Who Made Independent Music, Original Rockers is due to be published by Faber & Faber in April 2015.