Regular Caught by the River contributor Richard King’s second book – Original Rockers – is an incredible, transportational read. It takes place in a dusty recent past in an independent record shop (Bristol’s Revolver) and offers a glimpse of a hidden history – one where conversations and thought patterns drift mesmerically through film, art, the countryside, friendships and music. The book is published next week and it’s fantastic. We’re extremely pleased to be able to run this extract from the book thanks to Richard’s publisher Faber & Faber.

The illustration of the original Revolver bag is by the mighty Matt Sewell.

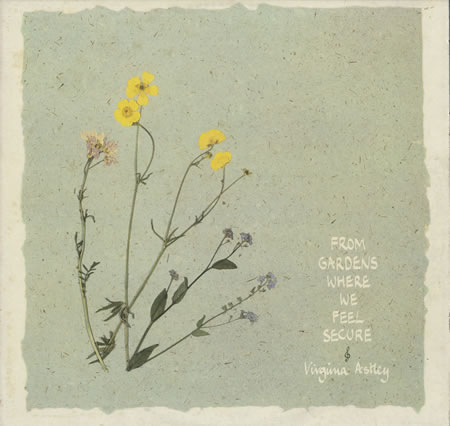

In the spring of 1982 the classically trained multi-instrumentalist Virginia Astley began making arrangements to produce an album, a recording that evoked the duration of a day in high summer from morning to nightfall. Astley had written the phrase ‘Sweet Third-Deep Grass’ in her notebook, from a memory of fielding at Third Deep during a game of rounders, a position where the ball is rarely in play and, unless playing against a strong team, the opportunity to become momentarily invisible and sedate among the long grass is assured.

Astley spent part of her childhood near the village of Moulsford in Oxfordshire where her father, a composer of film and television soundtracks, worked in a small recording studio-cum-study installed in the garage of the family home. An agreement was made that Astley could use this studio for part of the recording which, together with her degree from the Guildhall School of Music, gave her the confidence to recreate the passing of a day in the English countryside. She was also encouraged in the idea by Bill Drummond, who suggested he could release the finished recording on his Zoo record label.

She hired a portable Uher quarter-inch tape recorder and with her partner Russell Webb made field recordings of the wildlife and atmosphere of the Thames Valley. The idea for the record, to be titled From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, was highly original, although two records, she told me many years later, may have had subconscious influences.

The first was the 1971 recording of composer Gavin Bryars about a homeless man near Elephant and Castle singing ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’, a song whose origins remain unknown. Bryars edited the verses into a thirteen-bar loop that fell in slightly ragged 3/4 time. He used this discrepancy in meter to great effect by adding an orchestral accompaniment to the verse that accentuates the frailty inherent in the voice. The strings and brass in his arrangement rise and fall with an evenness so overwhelming it is difficult for the listener not to grow tearful. The original recording of ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ was released on Eno’s Obscure record label in 1975, three years before Music for Airports, the other subliminal influence on From Gardens Where We Feel Secure.

The music was written in the same key as the field recordings Astley made. These tapes of wildlife and rural hubbub were then cut and edited by hand into loops. Side one of the album, the ‘Morning’ side, begins with the dawn chorus recorded at 5.30 a.m. on Sunday 25th April; the title of this first piece, ‘With My Eyes Wide Open I’m Dreaming’, establishes the record’s somnambulant character as the birdsong is accompanied by Astley playing piano and flute. The piano part was then run backwards and added to the mix, a process that was repeated through much of the record and contributes to its unearthly atmosphere.

‘A Summer Long Since Past’, the piece that follows, is one of the few instances of vocals being used on the record. The wordless singing was by Astley and her eldest niece; their voices are in a high register and float behind the instruments as if sung by wood sprites.

The church bells recorded on the late afternoon of 6th June are a feature of the title track that follows. The tower to which they belonged could be seen from Astley’s family home. At the end of this piece Astley’s younger niece, who was in the room nearest the studio, can be heard crying. As her sobs were in tune it was decided not to erase them from the tape. Elsewhere in the piece the sound of a door being closed, recorded by accident, can also be faintly heard.

The final track on the ‘Morning’ side is titled ‘Hiding in the Ha-Ha’. Astley played a melody on the flute that was slowed to half speed, then pitched an octave higher and is heard as a motif throughout the song that concludes with the soft braying of Lilac, a donkey.

The ‘Afternoon’ side begins with ‘Out on the Lawn I Lie in Bed’ (the first line of Auden’s A Summer Night). The melancholy sound of a gate swinging on its hinges is heard through much of the piece, accompanied by xylophone and echoing piano lines.

A loop formed from the baaing of sheep, a noise that always sounds impatient or impudent, is heard on ‘Too Bright for Peacocks’ and is offset by the record’s most affecting piano part. The inherent eeriness in the record grows more conspicuous in the album’s final three tracks, as the hot afternoon of the day gives way to evening.

‘Summer of their Dreams’ is created from a tape loop of an oar creaking in its rollocks and brushing the surface water of the river. Many of the instruments added to the tape are played backwards. The overall effect is to suggest to the listener that while making their field recordings, Astley and Webb inadvertently captured the sound of a ghost river man rowing along the rural Thames.

‘When the Fields Were on Fire’ derives from a dream of Astley’s mother in which she saw stubble burning on a hill on the other side of the valley grow out of control. As her mother recounted the dream one morning, the Astley family heard fire engines driving in the direction of the same fields as in the dream. The sound of a telephone can be heard ringing in the piece, as can voices that carried across the water as Astley recorded the bells near the river.

From Gardens Where We Feel Secure concludes with ‘It’s Too Hot to Sleep’. The hooting of an owl recorded on Sunday 16 May is heard in counterpoint to a piano and rueful flute that fade slowly until the owl, a recording of electronic crickets and the ticking of Astley’s father’s study clock linger briefly, unaccompanied by instruments, before growing silent.

The nature and wildlife recordings Astley and Webb made on the portable tape recorder dated from the spring, 25 April in particular, a day that falls roughly a month after the vernal equinox. There is a sense that the sadness often felt during an English spring, a sadness that the light is starting to extend and in doing so is leaving one behind, was captured in these field recordings and their contents are filtered with vernal melancholy.

The eerie, otherworldly presence of From Gardens Where We Feel Secure in the listener’s imagination is partly explained by this elision of recordings of the spring countryside that is used to evoke the serenity of a day in high summer, as if the rhythm and progress of the seasons had been altered. In the year following its recording the album was released on 29th July, a fitting date for music of such reverie.

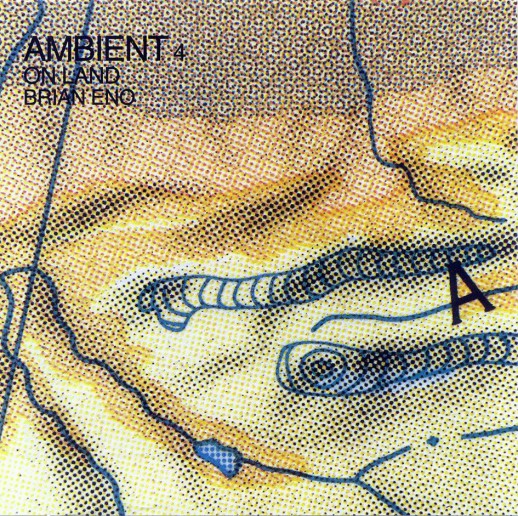

As Astley composed the music to accompany the field recordings made for From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, Brian Eno was recording his own evocation of an English rural childhood. The fourth album in the Ambient series, On Land, was an interpretation of his memories of the Suffolk coastal landscape. This was an interpretation Eno acknowledged might have been inaccurate, as he doubted the veracity of his memory.

Eno was concerned with the emotions prompted by memory, principally melancholy, a state in which he felt comforted by and associated with the Suffolk coast, rather than the accuracy of the memories themselves. Nor was he prepared to romanticise the English countryside as an idyll. In a 1982 interview he gave to promote On Land he was far from sanguine about rural life:

When you’re out in the country you hear sounds that seem quite lovely and pastoral, but those too are probably the sounds of emergency. That little bird singing is probably sounding some kind of alarm.

The producer built a fully sound-proofed studio, eleven by twelve feet, in his SoHo loft and talked of entering a ‘sort of sacred space’ as he began his working day in this sealed and controllable environment. Here, in this room that overlooked Broadway, Eno re-imagined the atmosphere of rural isolation he had experienced in East Anglia as a child, and as his eyes cast over the flickering monitors in his studio he created an aural equivalent to the Suffolk gloaming. He would regularly adjust and alter the lighting in his workspace and listen again to the pieces either in a diffused light or in darkness, as though by abnegating the temporal world he allowed himself a more direct route to the subconscious he was dredging for the record’s inspiration.

During the recording Eno manipulated found sounds, such as the rattling of discarded metal or wind noise, to create transient and uncertain undertones.

‘Lantern Marsh’ is one of the album’s more overwhelming pieces and is named after the marshland growing around Orford Ness, the twelve or so miles of shingle near Aldeburgh whose saltings are dashed by the unforgiving waves of the North Sea. The lanterns of the marsh were combustible gases rising from its mire that produced glowing wisps of light that terrified its inhabitants, and occasionally led them to their death as their attempts to grasp their luminescence led them into the quickening mud pools. ‘Lantern Marsh’ begins with an ominous cry one might associate with wildfowl. These bird cries, and the listener’s imagination, are then subsumed by an unnerving sound that produces a sense of electric horror.

The baleful presence of the lanterns had long been a source of trepidation. In the seventh century St Botolph decreed that the malodorous swamps around the Ness at Iken be drained in order to expel devils.

Orford Ness was commandeered by the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War then used by the RAF until the late 1950s ,when the area was permanently sealed off from the public. A decade later a network of hangars, bunkers and strange, pagoda-like edifices and rows of gaunt fan pylons were constructed on the shingle as the Ness became the headquarters for Cobra Mist, a backscatter radar system developed to detect signals of an incipient nuclear attack. The system had faults, unknown frequencies regularly interrupted the surveillance equipment with indistinct noise and the station was disbanded in 1972.

On the coast 140 miles south of Orford Ness is Dungeness power station, a more visible nuclear building standing on shingle, in sight of which Derek Jarman, when not working in London or in the city for hospital visits, lived at Prospect Cottage, a former fisherman’s lodge.

The final film to bear Jarman’s name was the posthumously released Glitterbug a collage of Super 8 footage that begins in the director’s early twenties when he lived in a warehouse on the wharf at Shad Thames. There, in what was unusual accommodation for the time, he had installed a greenhouse in which to sleep. A few seconds of footage of this glass bedroom and other details from this part of his life that he detailed in Dancing Ledge, his first volume of journals, appear on screen during Glitterbug.

Other moments from the ensuing decades, footage of friends, lovers and collaborators are cut together to form a remarkable self-portrait. The soundtrack that accompanies this footage with which it shares a discordant beauty is by Eno.

In Modern Nature, the volume of his journals that cover his life at Prospect Cottage, Ambient 4: On Land is one of the few pieces of non-classical music Jarman notes listening to:

28 August.

‘Eno’s On Land is the music of my view; a crescent moon under a dog star, clouds scudding in the grey dawn. I tidied the wood from the back of the house and spent the afternoon picking blackberries for jam. Noticed very few butterflies at the Long Pits, which have almost dried up; but a host of large dragonflies. The blackberries are just ripening and cascade across the light green bushes, blood-red like raw meat. It was hard work and I got torn to bits.’

In another entry Jarman writes of his admiration for the young author Denton Welch who wrote of the English countryside during the war years

10 February.

‘Finished my breakfast on the sofa, covered by my grandmother’s old travelling rug I read Denton Welch’s memoirs. Crystalline descriptions and acute observations. I wish writing came naturally to me.’

On first reading these lines I was struck by the symmetry of one writer of a journal commending another. When I finally came across a copy of Welch’s out-of-print journals I was similarly struck by a passage that might equally have been written by Jarman to describe his surroundings, (although the landscape Welch describes differs from that of Prospect Cottage):

15 June.

‘Raining, aeroplane droning, trees soughing,I am lying in bed now, so I imagine, as I have imagined how many times before, a stone cottage on some heath or moor. A cottage that is reached by a footpath winding through wet grass and heather, bracken, harebell, thistles.’

This evocation derives from a sense of the English landscape that includes the gardens where Virginia Astley imagined we might feel secure, the coastline of Brian Eno’s Suffolk childhood, and Prospect Cottage and its garden created by Jarman’s visionary imagination.

During the period when I was listening to Deux Filles, I visited the cinema to see Blue, the last film to be released by Jarman when alive, and noted from the poster that the film’s music was composed by Simon Fisher Turner.

As the film progresses the audience’s eyes learn to focus and focus again at the expanse of ultramarine monochrome that appears to float on the screen. While watching Blue I thought for a time I was staring at a river, and imagined a current and began to determine its strength. This must have been a common experience for those watching and as the film progressed a hesitant but noticeable empathy developed between those of us present, as though together we were learning to see in a particular way for the first time.

In quiet passages of the soundtrack I recognised a tone in Fisher Turner’s contemplative score and heard again the circulation of air hover like a breath over every note. In these reflective moments, when the richness of Jarman’s voice enhanced the poignancy of the memories he described, I was reminded of an entry in Modern Nature the book of journals he wrote while resident at Prospect Cottage.

He describes the intensity of the heat and languorous haze in which he finds himself drifting through a late summer’s day. At one point Jarman has achieved such a becalmed state that by some form of alchemy he appears to have altered time to his preferred pace. He is aware of little else other than the sound of seed heads cracking in the sunlight and scattering their contents on the pebbles below.

This serenity is all the more powerful for being interrupted by the pain and suffering evident in other passages in Blue.

Inspired by the soundtrack to Blue I determined to play On Land the following day in Revolver. A photocopy of an essay Eno had written to accompany the release had been inserted in the second-hand copy I found.

We feel affinities not only with the past, but also with the futures that didn’t materialize, and with the other variations of the present that we suspect run parallel to the one we have agreed to live in.’

As I read this sentence I was reminded again of ‘Burnt Norton’

Time past and time future

Allow but a little consciousness.

To be conscious is not to be in time

But only in time can the moment in the rose-garden,

The moment in the arbour where the rain beat,

The moment in the draughty church at smokefall

Be remembered; involved with past and future.

Only through time time is conquered.

The pastoral is inseparable from memory, as is the air circulating the subdued note played in isolation that, in the words of Jarman describing the effect of watching Blue, ‘transcends the solemn geography of human limits’.

Extract taken from Original Rockers by Richard King, published by Faber on April 2nd 2015. – the book is available for pre-order in the Caught by the River shop now. Virginia Astley will be joining us at Port Eliot Festival this summer.