Richard Williams pays his respects;

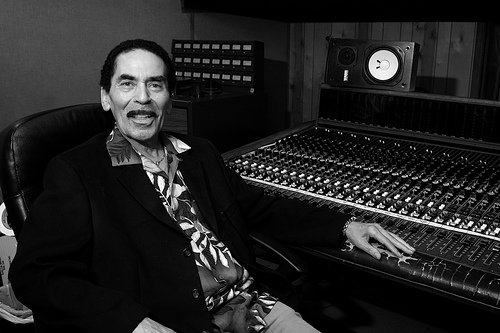

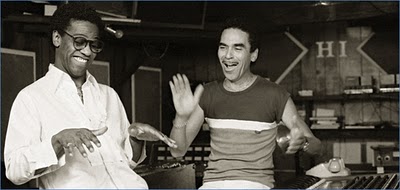

It was when Al Green sang “Back Up Train”, his first record, during a rehearsal at a club in Midland, Texas one afternoon in 1968 that Willie Mitchell realised the singer might have something special. Mitchell, who died in Memphis on January 5 at the age of 81, was then on the road with his own band promoting his hit version of King Curtis’s “Soul Serenade”, and was struck by the effect Green created when he sang at low volume. He invited the singer to relocate from Flint, Michigan to Mitchell’s base in Memphis, having persuaded the owner of Hi Records to take the risk of giving the young man $1,500 with which to go back home and pay off his debts first.

The gamble paid off. Mitchell told Green it would take 18 months of hard work to make him a star, and so it proved. After a initial series of unremarkable singles, the producer’s campaign to persuade a sceptical Green to sing softer and softer finally paid off in 1970 with“Let’s Stay Together”, in which the lazy slap of the drummer’s backbeat, a watery Hammond organ, a loping bass line and a minimalist arrangement for grainy horns and sweet strings created the backdrop for Green’s superbly restrained vocal. This was southern soul in excelsis, as Jerry Wexler would have said. Green and Mitchell never looked back.

“We used some nice diminished 9ths with Al,” Mitchell told the author Peter Guralnick, giving a hint of the musical sophistication that went into the making of Green’s simple-sounding records. Like so many of the musicians who were at the heart of R&B in the 1950s and soul in the following decade, Mitchell had received his training in jazz. Where the Mayfields and the Marthas came from the church, the Mitchells – and the King Curtises, the James Jamersons and the Maurice Whites – emerged from the crucible of swing and bebop, in which technique was highly prized and assiduously developed. Their instrumental skills and sight-reading ability made them particularly useful to arrangers and producers with only three hours in which to cut a handful of sides on a untutored and perhaps indisciplined singer. Initially a trumpeter who led his own band, the ambitious Mitchell made an early move to the studio control room, becoming one of the most successful and influential producers of soul’s golden age.

As a jazz trumpeter and bandleader turned million-selling soul producer, his career in many ways resembled that of his near contemporary Quincy Jones. He was born in 1928 in Ashland, Mississippi, and became part of the Memphis scene while he was in still in school, joining the big bands of Tuff Green and Al Jackson Sr. His early studio experience as a sideman included B.B. King’s first recordings, and like that great blues guitarist he spent some time studying the Schillinger system of composition, popular at the time among young black musicians bent on improving themselves. After a spell in the army in the early 1950s he started his own band in Memphis, attracting some of the best of the city’s young musicians, including the trumpeter Booker Little and the saxophonists Frank Strozier, Charles Lloyd and George Coleman, all later to become prominent figures in modern jazz, and the drummer Al Jackson Jr, the son of his former employer and a future cornerstone of Booker T and the MGs and of many of Green’s recordings.

Mitchell provided arrangements for Sam Phillips’s Sun Records in the late ’50s, but it was his association with Joe Cuoghi’s Hi label, beginning in 1959, that defined his career as an A&R man and producer. As well as “Soul Serenade”, his own hits included “Everything is Gonna Be All Right”, a Jr Walker homage which, with its equally powerful B-side, “That Driving Beat”, provided perfect material for British dancers in 1965, taking its place between “Road Runner” and “Mr Pitiful”.

Just as Motown was losing its edge and Stax was falling apart, Mitchell’s recordings with Green, Otis Clay and Syl Johnson revived a genre in danger of going stale. Moving away from the drive of Motown’s Funk Brothers’ drive and the strut of the Stax house rhythm section, that soggy, swampy backbeat, contributed by Jackson Jr or Howard Grimes, meshed with the instruments of the other Grimes brothers – Teenie on guitar, Leroy on bass and Charles on Hammond organ, all groomed by Mitchell to become masters of understatement – to take the music in an entirely new direction. That irresistibly slack, deep-toned backbeat was transferred by another producer, Thom Bell, to his work with the Stylistics and the (Detroit) Spinners, and thence to disco.

Apart from Green’s masterpieces – of which “Simply Beautiful”, in which Mitchell creates the illusion of catching the singer in the midst of a private reverie, may be the most extraordinary — for this listener the producer’s work reached its apogee with Ann Peebles’ heartwrecking “(I Feel Like) Breaking Up Somebody’s Home” and “I’m Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down” and O.V.Wright’s covers of Mable John’s “Your Real Good Thing (Is About to End)” and Benny Latimore’s “Let’s Straighten It Out”, in which his artistry and innate musicianship are most sumptuously deployed. What Willie Mitchell understood, perhaps better than anyone who ever lived, was how to sweeten a down-home record without forfeit its soul.