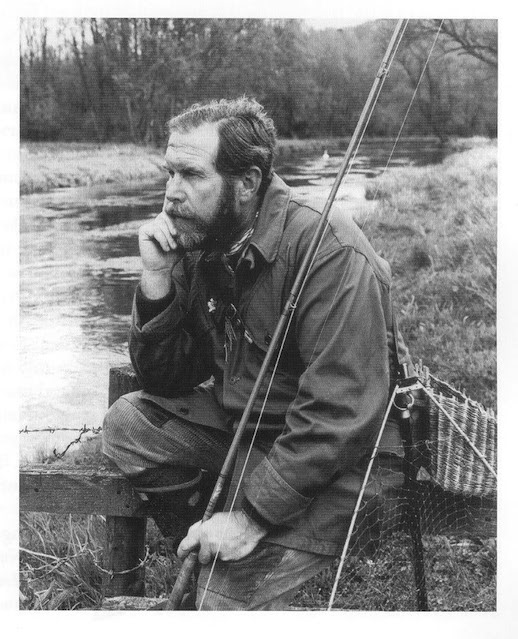

Oliver Kite, master fly-fisher and presenter of Kite’s Country

Oliver Kite, master fly-fisher and presenter of Kite’s Country

Joe Moran, author of Armchair Nation, takes a look at early TV fishing programmes:

Fishing on television began in earnest with the launch of the ITV regional channels in the late 1950s. Southern Television’s catchment area ran along the south coast from the New Forest to the agricultural prairies of Kent. Its chalk streams were some of the best fishing waters in the country, and the programme controller, Roy Rich, wanted a series about the region’s speciality, fly fishing, then a rich man’s sport and thus attractive to advertisers. So began, in 1959, Jack Hargreaves’s Gone Fishing, which mutated the following year into a much-cherished series about the countryside, Out of Town. Its format barely changed in 21 years. Viewers discovered Hargreaves in a set made to look like a shed, dressed in tweeds, gumboots and a fly-festooned cap. Sat at a trestle bench and smoking a briar pipe, he would simply start talking, without introduction, about an old country skill like cider making or onion stringing, before leading into a film about fishing for roach or cutting the Winchester water meadows.

Hargreaves avoided that glassy, eyeball-swivelling, autocue stare at the viewer, for he had intuited that the most successful television presenting is really a form of soliloquy. He had no script, believing that stumbling over words and repeating himself was more natural, and he did not always look at the camera because he felt that people in conversation often looked away from each other. ‘I’m not talking to two million people 20 miles away,’ he mused. ‘I’m talking to three people exactly 14 feet distant. That’s the average size of any TV audience, and the distance they sit from their set.’ His sentences had a comforting, epigrammatic quality. The countryside would fall apart without baler twine. There’s nothing more dopey than a dopey cod. Freezers have taken the fun out of beans. In the Southern region, Out of Town regularly beat Coronation Street in the ratings.

Another local programme, In Kite’s Country, presented by a former army major called Oliver Kite, was also regularly in Southern Television’s Top Ten. At the age of 35, Kite had suffered a coronary thrombosis and the army had sent him to write training manuals at the School of Infantry in Netheravon, which had one of the finest chalk streams in the country, the Upper Avon, nearby. He set about learning all he could about trout fishing from his mentor, Frank Sawyer, the Upper Avon river keeper and inventor of the pheasant tail nymph. Kite proved to be a natural, aided by superb eyesight which allowed him to see what was happening under water without the aid of sunglasses, which he refused to wear because he thought it was unfair on the fish. Southern Television got word of him and he began appearing on Day by Day, its early evening news programme. In June 1965 he was invalided out of the army. The next day, Southern offered him a weekly 15-minute programme, In Kite’s Country, starting in September, on the day his army pay ran out.

Like Hargreaves, Kite was a ‘spieler’, simply ad-libbing in his slow, rich voice over film of him catching grayling, sometimes while blindfold or with a paper bag over his head. He had a warm Wiltshire accent with a slight lilt from his Welsh childhood, and his style was bluntly poetic: ‘You throws it in, you pulls it out, and when you can’t, you’ve got one.’ He received about 350 letters a week from viewers, a huge number for a programme not shown outside the region. One man, who wrote to say how sorry he was that he would no longer be able to watch In Kite’s Country now that he was leaving the area, turned out to be awaiting release from Parkhurst. When Kite died of a heart attack on a river bank in Overton, Hampshire in June 1968, aged just 47, 2000 people came to his memorial service at Netheravon church.

The only problem with these early fishing programmes was that they were in black and white. 405-line black and white was not high definition enough to show a fishing line clearly, so viewers could only really see the presenter waggling the rod in the air. But when BBC2 began colour transmissions in 1967, one of its most popular early programmes was Anglers’ Corner, with Bernard Venables, which conveyed beautifully in 625-line colour the choreography of rod and line against the changing light of a day on the water. Venables had done much to make fishing popular in the postwar years with his ‘Mr Crabtree’ cartoon in the Daily Mirror. This character had originally been devised by Jack Hargreaves, as a strip about gardening drawn by Venables. In the winter, with little to do in the garden, Mr Crabtree went fishing, and so evolved Venables’s bestselling book, Mr Crabtree Goes Fishing, published in 1948, which became the world’s bestselling fishing book after Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler. Venables thought that fishing should be as much about enjoying the flora and fauna as about catching fish. ‘Angling is applied natural history,’ he said. ‘It seemed to me that the whole of nature was sewn up in fishing. It was the biggest expression of my delight in nature. It was my principal delight in life.’

By the 1970s, Jack Hargreaves’s Out of Town was in colour and being shown not only in southern regions but throughout the country. It now aimed at being evocative as much as informative, giving urban viewers what Roy Rich called ‘a dream of the green fields beyond’. Outside the Southern region they saw Out of Town episodes out of synch and long after they were made, happily watching fish being caught in the middle of winter or lambing in August. Noting that Hampshire, where he lived, emptied in the morning as people travelled to London for work, Hargreaves realised that many of his viewers no longer had any real contact with rural life. ‘I’ve got to hook every sort of viewer, particularly the ones who have never held a fishing rod,’ he said. ‘You can’t do that just by showing them a lot of floats and telling them how to breed champion maggots.’

The Clydeside trade union leader, Jimmy Reid, watching in Glasgow, thought Out of Town ‘a gem of a programme’ and ‘the answer to those TV moguls who plead poverty as an excuse for diminishing standards’. Another fan of the programme, George Harrison, now living in semi-rural seclusion near Henley-on-Thames, had the idea, while watching one episode on restoring old leather books, of publishing his autobiography/lyric book, I Me Mine, as a hand-bound limited edition.

Fishing, with its relative lack of drama and incident, is not obvious material for television. Nowadays, fishing shows tend to be presented by celebrities and to focus on ‘extreme fishing’ in exotic locations. But the success of these earlier fishing programmes shows that television viewers, when they are given the chance, can be just like anglers – patient, attentive and amenable to slow, incremental pleasures.

Joe Moran is the author of Armchair Nation, a history of TV viewing, and he blogs at joemoran.net