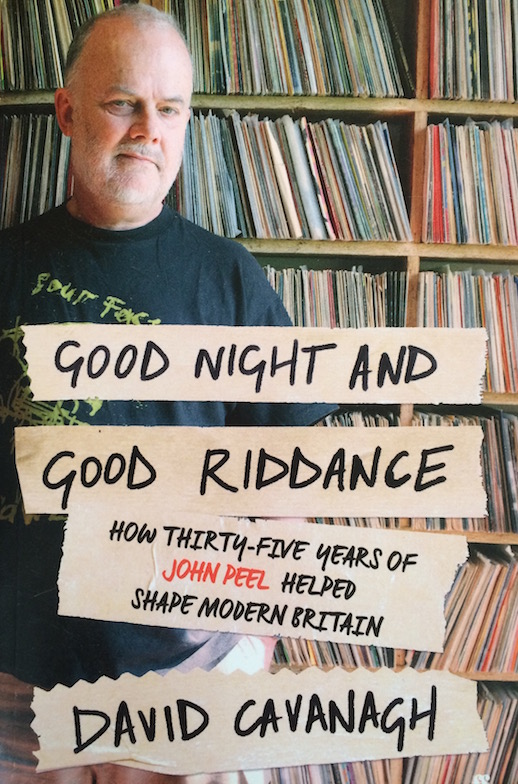

GOOD NIGHT AND GOOD RIDDANCE : How Thirty-Five Years of John Peel Helped To Shape Modern Life by David Cavanagh.

GOOD NIGHT AND GOOD RIDDANCE : How Thirty-Five Years of John Peel Helped To Shape Modern Life by David Cavanagh.

Faber & Faber, 620 pages, paperback. Out now.

Review by Andy Childs

I have a file somewhere of steadily degrading sheets of paper containing playlists of John Peel’s Top Gear programme from the late 60s and early 70s with my rudimentary comments scrawled beside each track. In a box somewhere there are tapes of some of these shows as well. Even though it sometimes felt like it, I was obviously not alone in my particular obsession. I knew a few like-minded souls – one of them had even managed to obtain a copy of the first Soft Machine album and a couple more had, like me, had their heads turned inside out by The Grateful Dead’s Anthem Of The Sun. But “listening to Peel” and discussing what he played with my fellow enthusiasts formed a large part of my social life back then as well as unwittingly helping to sabotage my formal education. It was easy then and it’s even easier now to over-estimate the importance of a lot of things in life – Eric Clapton, anything that football managers say and Adele’s new album – being but a few that immediately spring to mind, but should anyone wish to dispute the unprecedented and far-reaching impact that John Peel had on the development of popular music and the shaping of contemporary cultural life, theirs will surely be a lone voice in the wilderness.

Peel’s reputation as the ultimate musical taste-maker has, if anything, been steadily enhanced in the years since his untimely death in 2004, and in this hefty and absorbing volume David Cavanagh emphatically reasserts this self-evident truth with a prodigious amount of research, a level-headed analysis of Peel’s many qualities and contradictions, and a sardonic sense of humour that the man himself would probably have approved of. In a breakdown of the music that was chosen for the extravagant opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympic Games Cavanagh astutely deduces that “Britain was presenting itself to the world as a John Peel nation.” Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, Dizzee Rascal, Frank Turner (ex-Million Dead), Pink Floyd, The Sex Pistols, New Order, Frankie Goes To Hollywood – music chosen by director Danny Boyle, music that was first aired and often supported by Peel when hardly anyone else seemed to care. Without Peel it’s arguable whether any of these acts would have survived and flourished. Would it have been as surprising (but rather more satisfying) to him, as it is to all of us, to know that the music he almost single-handedly pioneered is now so embedded in mainstream contemporary culture? More pertinently, do the various clueless Beeb bureaucrats who regularly tried their best to marginalise Peel and diminish his influence have any idea how pinched and arid our music and our lives could have been had they succeeded in their evil machinations? One hopes they read this book, chastened and humbled.

The opening chapter, Peel Nation, neatly encapsulates Peel’s career from his early days as a DJ in the U.S., through his stint on pirate Radio London with perhaps his most innovative show, The Perfumed Garden, and then his move to the BBC and Top Gear, Night Ride, and the John Peel Show. Not forgetting of course his very comfortable foray into the homes of middle England, Home Truths. But it’s Peel’s music programmes that are the real subject of this book and without, thankfully, attempting to compete with the various websites that have archived every playlist and session that Peel’s thirty-seven uninterrupted years on radio have yielded, Cavanagh instead strategically handpicks a number of shows from across those years, lists some of the music that Peel played, prefaces each show with a random, often political news item from the time and then weaves in a summary of Peel’s current musical discoveries with his ongoing love/hate relationships with the BBC, his fellow DJs, and various artists including Marc Bolan who, along with The Byrds, Neil Young and probably Rod Stewart gave him a lesson in the emotional pitfalls you’re likely to encounter when you start assuming artists are your friends. There’s also a more significant and ongoing theme of conflict in the narrative as well. Whilst we’re all aware now of how seemingly prescient Peel’s musical taste was, it’s still surprising to learn of the constant struggle he had to endure to convince the hierarchy at the BBC that he was worth his time on air and that the music he played deserved to be heard. For years his was the show that was re-scheduled, shortened, threatened and generally mucked about with whenever change was in the air, but through a combination of smart political manoeuvering, bloody-minded bravado and luck he succeeded in keeping his job and retaining his position as Radio One’s supreme outsider. As Cavanagh cleverly details with his choice of programmes, one of the secrets of Peel’s comparative longevity on ‘pop’ radio was his willingness and eagerness to embrace new musical trends well before anyone else on radio realised what was going on, thereby staying ahead of the game and firmly on the cultural high ground. He was actually ruthless in his rejection of music that, to him, had outlived its relevance, no matter how enthusiastically he’d suported it in the past. For nearly a decade his was the voice of ‘underground music’, the cultural spokesperson for hippies, prog-rockers and folkies alike, but then punk came along and Peel’s programmes changed, not overnight but stealthily, even cautiously, to lead his mostly bewildered audience into territory unknown. And he continued to introduce his faithful flock to new musical genres – some fairly extreme and hard to stomach I would suggest – throughout the rest of his career. It is this radical sense of programming that distinguishes him as a DJ but also, somewhat inevitably, it poses questions about the authenticity of his chameleon-like behaviour. When he remarks of bands that he once championed : “I can’t believe I ever thought that they were any good at all. I hope that’s always the case”, we surely have to ask ourselves whether he played the music he did because he genuinely thought it was good or because, as no-one else was playing it, he felt duty-bound to do so. One could argue that this periodic re-appraisal of his taste in music is evidence of a premeditated strategy to ensure his pioneering reputation remained intact (an accusation that one-time arch enemy Tony Blackburn has predictably posited). Cavanagh poses this question in so many words but of course it’s one that can never be satisfactorily answered. He talks of Peel’s “capricious taste” in music and cites examples of bands, like Felt for instance, who blame their lack of success on never being able to appeal to him. But Peel never liked Springsteen, Ry Cooder, Tom Waits or Blur and they seemed to have managed OK. And he regularly played records from the years before he took to the airwaves – old rock’n’roll, R’n’B, soul classics that were apparently immune to his own idiosyncratic brand of revisionism. Peel was almost gleefully curmudgeonly and unpredictable to the end. One of his producers and soul-mate, John Walters, once said that Peel’s taste was that of an adolescent forever excitedly discovering new music and that when he finally reached puberty we’d all be in trouble, or words to that effect. In the context that Walters suggests I don’t think he ever did and for that, whatever our musical tastes, we should be grateful.

David Cavanagh, author of the excellent history of Creation Records My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry For The Prize, has performed a valuable service in documenting, in such an entertaining and accessible way, the career of one of the country’s greatest broadcasters, period. Almost in homage, the BBC have created an entirely new radio station to try and fill the void he has left, but we still miss him.

Good Night and Good Riddance features as one of Rough Trade’s Books of the Year, and is available to purchase here