review by Tom Fort.

If your idea of a fishing book is a specimen on every page, with lashings of rod-bending action, screeching reels, rods bucking like a wild horse and so forth, then this is very definitely not the book for you. In fact I’ve never encountered a fishing book with fewer fish: two trout, to be precise, one of about a pound and a half, the other less than a pound. And 300 plus pages to tell the story.

So this is no conventional addition to the library. The fishing is key to it, but it is about many other matters, some of them even more important than fishing. There are rocks and mountains, fathers and grandfathers. There is friendship and love and betrayal. The past is here, the present, and the future. And there is Scotland, in particular a small part of it, very special to those who know it.

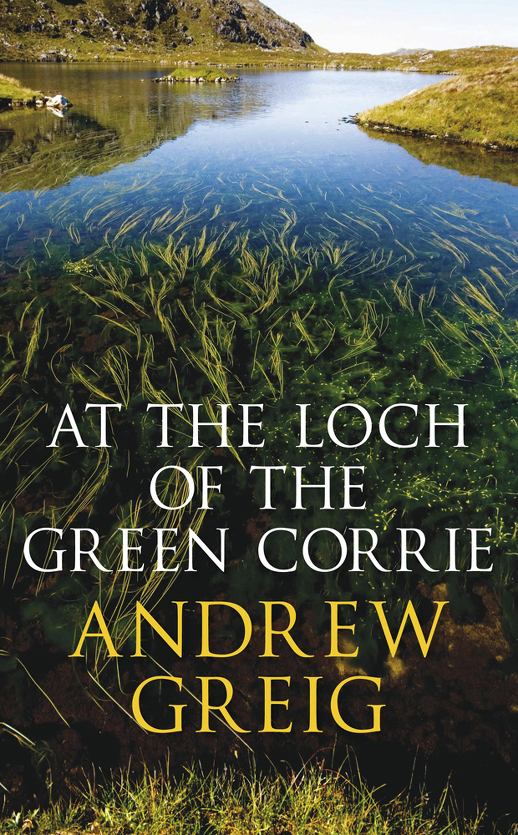

It is called Assynt and lies north of Ullapool, where the north-west coast is split by one sea-loch after another, and where the rivers of the east almost meet the rivers of the west. It is a place open and wild, empty of people, where one bare hill sits isolated from the next on a great bed of immensely old, immensely hard Lewissian gneiss. A place – as Andrew Grieg puts in a way highly characteristic of his style “austere, indifferent, problematic, unyielding, making no concessions at all”. Until the scourge of salmon farming was unleashed, the lochs and the rivers that connect the lochs to the sea were full of sea trout and salmon. That is all gone. But there are still the brown trout, in every loch, big, little, obvious, hidden. Among them the Loch of the Green Corrie.

One of those who knew this land and its lochs – well enough to be accorded the honour of life membership of the Assynt Anglers – was the Edinburgh poet Norman MacCaig. And that is where this story begins, in an encounter between the old poet – too old now to fish and long separated from this wellspring of his imagination – and the young poet, a disciple. Were they friends? Grieg says not. But he clearly revered the older man, and reveres his verse. So when MacCaig urged him to Assynt to find the Loch of the Green Corrie, it was as if he’s been given a sacred mission.

It takes some finding. Its real name is another name, and he cannot check his map with MacCaig because MacCaig is now dead. But he has the name of a friend of the poet, living in Lochinver, “a man of few words and long silences.” After one of these silences the friend suddenly says: “I miss him”. Then he agrees to point the way, with some more words, which all fishermen will recognise – “if the wind’s from the east it’s no use.”

Greig and two friends, who are brothers, plod the long plod into the bare hills. They find the loch and the wind is in the east and it is no use at all. Greig – who is clearly no sort of a real fisherman – casts until his shoulders ache. They return to their camp, try again another day. Eventually one of the brothers catches a trout (page 225 – you see what a I mean about the fish count). Grieg the poet (but no fisherman) catches nothing, which nags at him when the trip is over.

In time he goes back. By now the book is the thing, and he needs some background, particularly on MacCaig’s long-time fishing partner, AK. When AK died – “earlier than he should have through whisky” – MacCaig came to the funeral. “Norman was white, haunted and scarcely spoke”, Greigh writes, drawing on the memory of AK’s nephew and applying a novelist’s touch. MacCaig wrote a poem which began: “I went to the landscape I love best/and the man who was its meaning and added to it/met me in Ullapool”.

By dint of digging around and asking some awkward questions, Greig acquired the material he needed. There was time to fish again, so he went in search of another of MacCaig’s loch, this one “clasped in the throat of Canisp, that scrawny mountain”, as one of the poems has it. But that’s no use either. In the end he finds a loch for himself, Dubh Meallan Mhurchardh, “the black loch of Marchadh’s hillock”; where, on page 313, he catches his own trout. And he gives thanks.

There is a great deal more here than a quest for water and a man’s fishing past. Grieg tells the story of the old poet and the landscape that moved him so deeply touchingly and rather beautifully. But into it he cuts many other stories, many of them of himself: his relationship with his father, his broken marriage, a suicide attempt, a highly exotic love affair with J, who was in rock music and knew Bob Dylan and died of alcoholism, depression and malnutrition, his own writing, his new love. Other Scottish poets flit in and out – MacDiarmid, Mackay Brown, Sorley MacLean. This is an intensely Scottish book, and proud of it.

One or two of the digressions outstay their welcome – I could have done without the potted history of the geologist James Hutton (even if he did crack the mystery of the age of the earth) – but overall Greig’s fragmented, kaleidoscopic approach works well, in a slightly self-consciously poetic way. And I loved the way he used Norman MacCaig’s own poems, which are wonderfully simple and easy, to signpost his way.

Above all this book has captured the magic of place, a special place. Its pages are steeped in the scents of heather and bog, and the winds of the north – whether from the east or the west – blow through them. There would be worse ways to spend a little time than to wander the hills north-east of Loch Assynt with a rucksack and a kettle and a rod and reel, and hope to hit the Loch of the Green Corrie when the wind is in the west. Of one of his days, MacCaig wrote: “We walked home, ragged millionaires/ our minds jingling, our fingers/ rustling the air.” That is the spirit.

copies of At The Loch of the Green Corrie are on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.00

Tom Fort’s latest book, Against the Flow, will be reviewed on Caught by the River later this week. Copies are now on sale in our shop.