Diva Harris talks to William Arnold about his 21st century homage to Victorian botany.

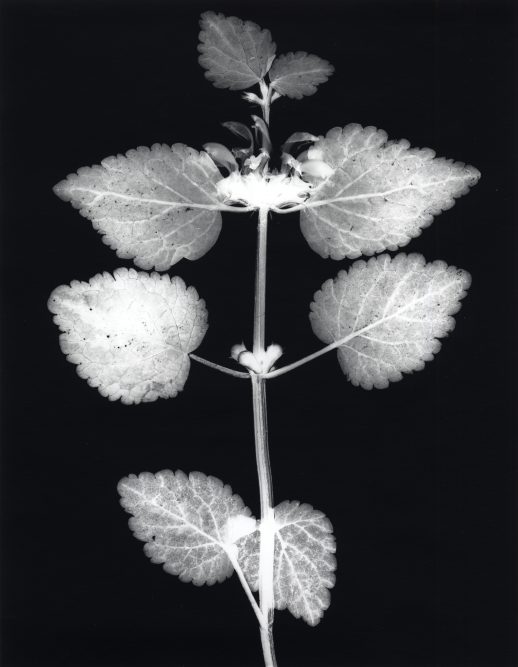

Yellow Archangel (Lamium gleobdolon)

William Arnold is a photographer living in Cornwall. Having chanced upon a copy of his Antler Press photo book some time ago and following him on Twitter, I began to notice the fruits of his latest labour, Suburban Herbarium, springing up on my timeline.

Pared-down yet enchantingly beautiful, William’s photographs document the plant species he encounters on regular lunch break walks around the western outskirts of Truro.

As someone who is unreasonably excited by anything which makes reference to popular Victorian practices (herbaria, floriography, hairwork…), I wanted to know more about the project, and was delighted when William agreed to answer my (possibly too) enthusiastic questions via email.

*

First off, what was it specifically about Victorian botany which appealed to you?

It was initially an interest in old photographic processes and the umbilical link between photography and science which drew me towards Victorian life sciences. That, and an interest in nature writing, particularly Henry David Throreau’s Walking and Richard Jeffries’ Nature Near London. I have always gained great fulfilment from the natural world, but felt a loss of the link through my day job and its associated pressures. I wanted to reconnect.

A previous project of mine – Outside City Walls – is a series of large-format landscape photographs I took on lunch break walks. They were processed in a DIY developer made using the coffee granules supplied in the staff room. I was heavily influenced by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts’ Edgelands, alongside the mid-19th century writings of Thoreau. I was interested in the notion of preserving this contemporary edgeland wilderness environment in aspic.

The botanical survey [Suburban Herbarium] came about through noticing year on year the incredible biodiversity of this area that 20 years ago would have been pastureland, but is now a mixture of housing estates, building sites, business parks and a college campus, cut through by these old country tracks. I found the mix of native species and garden escapees intriguing.

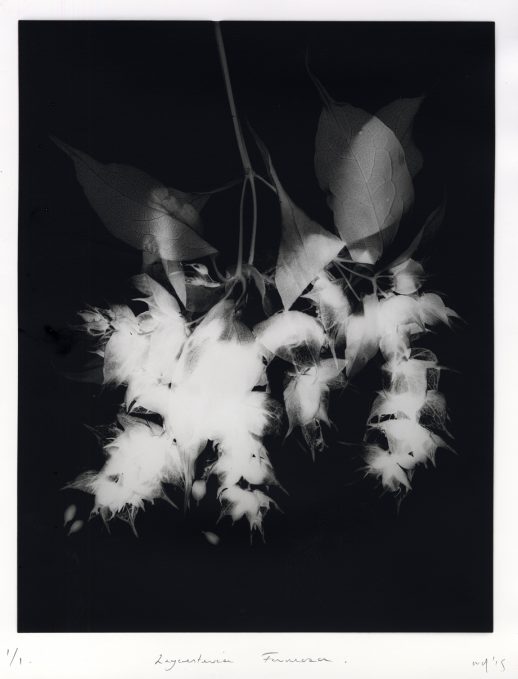

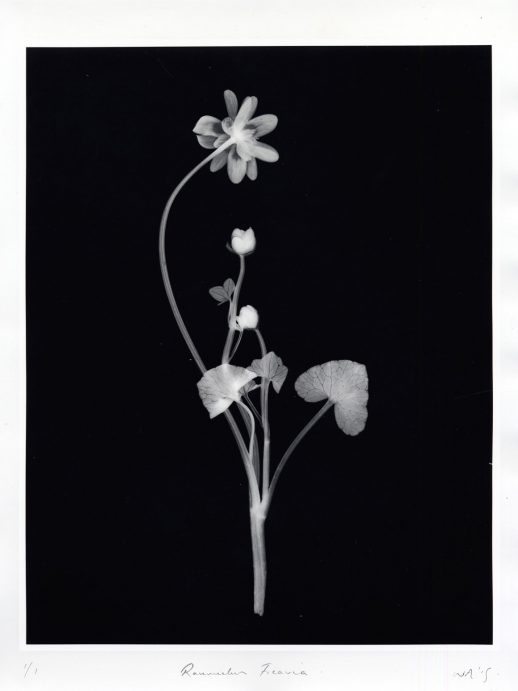

So, the work follows on from Outside City Walls, but I wanted to make something that was very much more documentary in nature and that would focus on one aspect of the environment. The process was chosen because it forces a focus on the form and detail of each of the specimens, devoid of any other context – the flat form and similarities in method call to mind Anna Atkins’ cyanotype botanical portfolios and Henry Fox Talbot’s first photogenic drawings.

Lords-and-ladies (Arum maculatum)

I’m really interested in the form you chose – as you say, it forces the viewer to focus on details of the plant they wouldn’t necessarily normally pay attention to. Am I right in saying that there’s also an impermanence to pinhole photography? That the photographs fade with age?

The images made are as permanent as the photographic media onto which they have been recorded. Many early photographic prints made with processes such as salt printing are quite sensitive to light and definitely need to be stored away from sources of UV radiation.

The very long exposure paper negatives will fade away and can’t be fixed, but if you make the picture onto film, or properly fixed photographic paper, they’re permanent (with sensible storage).

The Suburban Herbarium photographs are very permanent as they are printed to archival standards on fibre-based gelatin-silver photographic paper. I’ve worked quite a lot with pinhole photography in the past, but these photographs are made by a ‘cameraless’ method. Light is projected through the plant specimen onto a sheet of light-sensitive paper, thus creating a negative of the plant in very high detail. This process requires the specimen to be sandwiched between glass plates, which references flat herbarium pages – though oddly, there is quite a three-dimensional degree to the photographs. They’re much much better viewed as objects in real life than on the screen. They’re intended to be an archive so I would love to keep the set together and for a museum to take it at some point.

Well I was going to try and say something profound about a transient form mirroring the seasonality of this work, but I guess I’m barking up the wrong tree…although I suppose, actually, the fact that you’re adding permanence to something which is usually so fleeting might be just as interesting to think about…

Exactly…and I am interested in how work concerned with these edgeland environments ends up becoming a mirror of traditional landscape romanticism. I’m sort of trying to elevate these weeds to a more rarified status.

Do you think a lot of the species you’re photographing are overlooked, then?

Yes, or are often pests – invasive garden escapees.

Have you got a particular favourite of the specimens you’ve photographed which you think gets a bad rep? And a favourite from the series in general?

Ha! People get quite worked up about invasive non-native species – Japanese Knotweed being the main offender as it swamps everything and will regrow from a tiny tiny piece of plant. There isn’t any Japanese knotweed on my walk, but there is some Himalayan Honeysuckle (Lycesteria Formosa). It’s beautiful, but non-native and invasive.

I really do want the work to be simply about what is there but if pushed for a favourite plant in general, for personal reasons, probably lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria), on account of it being part of the very first regreening of spring – it’s a real sign of hope (if that’s not too cheesy). It seems a bit trendy these days to award yourself Seasonal Affective Disorder but I certainly find winter a tough time, exacerbated by being trapped inside at work through the daylight hours, so these lunch break walks are a real pressure valve and the celandines are a sign of easier times on the way.

I want to keep a documentary objectivity to this series as much as possible, giving all species equal weight – all of the the specimens are scaled to the frame of the photograph, so a tiny speedwell is presented at the same scale as a foxglove, for instance. This is obviously absurd from a scientific perspective, but I like the idea of levelling and the focus on form.

Have you got an end-date in mind for the project, or is it going to be a work-in-progress for the foreseeable future?

I’m working towards a book, as well as the archive set of original cameraless photographs, if I can find anybody interested in publishing the series, so at some point it will naturally wrap up.

I don’t want to set an absolutely defined end point and I know there are many species left to record, but I can’t imagine I would contribute much more beyond next year – so one more year of investigation. Hopefully I’ll bring some other contributors on board to provide a commentary from a scientific or culturally geographical perspective.

Of course this work revolves around a lunch break from my day job at a college, so should I change jobs, the series would come to a fairly abrupt resolution.

I have currently recorded over eighty species, so the work could be realised now. But I’d like to make it as comprehensive as possible.

*

A selection of photos from this project will be exhibited for the first time at a group show next month. PHOTO PIONEER | PHOTO PRIMITIVE runs from 8 July – 1 September at the Penwith Society Gallery, St. Ives.

Prints are available to buy here.

Keep up-to-date via William’s Twitter account and the Suburban Herbarium Tumblr page as species are recorded throughout the year.